for Hieronymus Bosch

death (noun)

/deTH/

Old English dēath, of Germanic origin; related to Dutch dood and German Tod, also to die. The act or fact of dying; the end of life; the permanent cessation of the vital functions of a person, animal, plant, or other organism. / Also as in an instance of this; (with specification) a manner of dying.

- We know death, though some know more than others. Death stalks, waiting for invitation, dressed as something you may know. Death creeps in peripheral sight, not in flowing robes but as hereditary illness, disease, legacies of violence and oppression.

There is no art to dying slow.

- Death pervades, persistent and rarely artful. To inhabit a certain space, a certain skin, means to know death more intimately, to court one’s own end consistently screaming into silence, “NOT NOW.”

- Not if.

- Not never.

- Just, please…

- not now.

- Not…

- Like…

- This.

- I failed to save my grandmother from death. Like so many living in poverty, preventable circumstances killed her. My mother, although considered middle-class, met similar conditions: diabetes, hypertension, stroke, hemorrhage, abrasions, wounds, and infection. My savings were depleted. Credit cards maxed. I had begun throwing collection letters from hospitals into the trash. I had stopped answering my phone to avoid speaking to debt agencies.

- I could no longer afford to keep my mother alive.

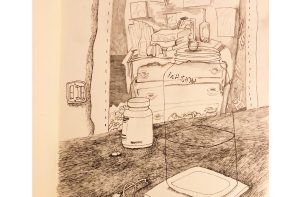

- So, I removed my dead grandmother’s revolver from the drawer of my nightstand.

- I carried the gun into my mother’s bedroom beside mine.

- While my mother slept and writhed in pain, I wept over her softly.

- I didn’t wake her.

- Feelings of uselessness subsided with the weight of the snubnosed revolver in my hand. The hopelessness dissipated with the movement of pulling back the cylinder release to unload all the bullets but one.

- And then I saw death as an intruder, standing in the doorway of my mother’s bedroom. Wrenching back the hammer, I fired wildly at the apparition. But no blasts accompanied the clicks from the weapon.

- As death inched closer, my mind fell silent.

- I pressed the barrel of the gun to my temple and pulled the trigger.

- The violent shake of the hammer connecting with the firing pin startled me and my thoughts returned.

- Death vanished.

- The sole bullet remained in the chamber.

- My mother snorted awake.

wealth (noun)

/welTH/

Middle English welthe, from well or weal, on the pattern of health.

The condition of being happy and prosperous; well-being. / Contrasted with woe, wandreth, care. / Of the world, a country, town, community, its people or members; hence (the common or public) welfare. / An instance or kind of prosperity; a felicity, blessing. Chiefly plural. / Abundance of possessions or of valuable products, as characteristic of a people, country, or region; the collective riches of a people or country. / Spiritual well-being. Often in the testamentary phrase for the wealth of (one’s) soul. (Obsolete.)

- Many believe accumulating wealth might ease one’s passing and salve the suffering before death. They strive to become those who die comfortably among their riches, like pharaohs and royals. They aspire for celebrity and nobility, to get rich or die trying.

- If cash rules everything around us, why couldn’t wealth intercede between this life and a death?

- I started saving: adopted schemes suggested by financial gurus and fiscally responsible friends, purchased stocks, lived cheap, looked into CD accounts and Roth IRA, set aside monies every week, every month, every year. But when death threatened loved ones, exorbitant medical expenses and the cost of caregiving leveled my net worth. I have yet to find a means to accrue the funds needed to insulate myself, and those I’d die for, against a cold fatality. The myth that making a million only requires perseverance, hard work, and a bit of luck doesn’t portray the whole truth. It is easier to hoard wealth where it already exists.

- I sensed the existence of “intergenerational earnings elasticity” long before I knew its name. I noticed a few of my friends at school would mention inheritances, trust-funds, or gripe about how little they received in their grandparent’s will. I noticed all of these friends had a different skin color than mine. Many of these friends had heirlooms, priceless trinkets they could bring in for show-and-tell, items and antiques they could trace along with their lineage to countries in Europe. They all knew where their families began. I knew some of my own heritage because my father emigrated from West Africa. My friends often punctuated their familial tales with quips about their ancestors’ poverty, how much their forefathers struggled to build prosperity in the so-called New World. Despite whatever stereotypes associated with their genealogy, whatever persecution their families faced, my friends’ ancestors had managed to thrive. Sometimes their stories would cause me to flush with shame, and I’d wonder why my ancestors hadn’t done a better job pulling themselves up out of scarcity to leave me something valuable I could measure.

- Now, as an adult, I recognize the many aspects of society designed to prevent upward mobility, and the challenges present at birth for paying wealth forward to the next generation. I identify with those accustomed to getting snapped back like a rubber band, segments of the population with less financial elasticity.

life (noun)

/līf/

Old English līf, of Germanic origin; related to Dutch lijf, German Leib ‘body,’ also to live. The condition or attribute of living or being alive; animate existence. / Opposed to death or inanimate existence.

- To suffer in the grips of death every day. To thrash against the design of governing systems and social constructs which promote monetary wealth as the only means of salvation, equality, and survival.

- When faced with the prospect of living and dying on one’s knees—an existence broke and tired leading to an unlawful end, weary and broken—it is difficult not to despair, not to lose faith and patience, difficult not to resort to spirited pride and greed. With death lurking through the doorway, one might overlook the waning soul behind projections of wealth, health, and valor.

- I understand the inclination towards nefarious actions to improve one’s quality of life. I don’t condone deciding to subjugate others, promoting violence, selling methods of destruction, taking, stealing, or breaking. I don’t agree with turning other lives into a commodity. I don’t approve of crimes against others as an acceptable response to the fear of death. But, I understand.

- I have five inexpensive tattoos, each a reminder of an instance in which I failed to end my own life: left leg, a Chinese character, dào, meaning the way, a path forward; above the Mandarin, a Bible verse citation, Romans 8:13-39, a scripture my grandmother gave to me years before she passed; left triceps, a Celtic cross comprised of interlocking lines and curves like a tendon; right forearm, an Edison bulb with a number two pencil as its filament.

- These patches of cheap, fading ink signify moments when the fear of living appeared too great to endure.

- The last tattoo rests on my left wrist: a pilcrow, commonly known as a paragraph symbol, a piece of punctuation used to denote a split from old capitula and branching forward faithfully into new passages, the start of another section.

faith (noun)

/fāTH/

Middle English: from Old French feid, from Latin fides. The fulfilment of a trust or promise, and related senses. / Attestation, confirmation, assurance; especially as in to make (also do) faith: to attest; to affirm, confirm; to give surety. / Belief, trust, confidence. / The duty of fulfilling one’s trust; allegiance owed to a superior, fealty; the obligation of a promise or engagement. Also as in to make faith: to swear fealty.

- In the effort to accrue and save what ruling structures cannot take, it is easy to miss the light overheard promising reprieve from the shadows.

- Hieronymus Bosch believed the temporal anguish of this world was immaterial to the glory revealed to God’s faithful after death. In “Death and the Miser,” a triptych panel created around the end of the 15th century, the Dutch painter encourages observers to remember their own mortality. Bosch incorporates common Ars moriendi imagery, Christian iconography depicting conflicts between good and evil, creeping demons, pleading angels, crucifixes, and personifications of death brandishing arrows. The painting urges the viewer to ignore the pain of all that conspires to do them harm, resist worldly temptations, give up the pursuit of wealth, and die well.

- But divinity too often feels tied to the same commodity culture it begs for servants to abandon. Faith too often reinforces greed and thoughtless consumption.

- What is the weight of wealth tithed to gold-glittering places of worship? What could be done for all people, here and now, in this life, with the money saved for spacious and ornamented churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples? How much does a misunderstanding of faith reinforce oligarchy and elitism, and further divide humanity into classes?

- I had learned to believe in the hierarchies wealth imposes, because this conviction gives stability and order to the uncertainty of human life and death. I’ve prayed silently to economy and then grieved in the discovery that equal participation does not promise equal safety, does not guarantee a dignifying end. My familiarity with death has illustrated that no amount of wealth can ever fully guarantee that I won’t be killed by one of the many problems overlapping the populations I’m bound to.

- Still yet, I have faith in our ability to ease each other’s suffering before death.

- Faith in one another can enrich life and cheapen the pain of death.

- When my mother lost the ability to walk and hoisting her repeatedly from the bed to the wheelchair threatened to tear my back; and the physicians at the dialysis center rushed her to the hospital; and she spent weeks in and out of intensive care units; and the medical center discharged her to a long-term rehabilitation facility; and a government tax penalty obstructed federal financial assistance for the daily health expenses; and I had to leave to avoid eviction from the costly ADA accessible apartment I had rented; and I had to sell and whittle my possessions; when I was homeless, and helpless, and broke, death appeared to me again.

- As death grew arms to hold me, I prayed to avoid surrender and found salvation in mortal hands, in the generosity of friends, the comfort of family, and the compassion of strangers. A community answered with hope. I received food and shelter and work and money and faith to persist, faith that, although life can feel isolating, I am not alone. My needs were met, necessities for survival and a response to the burning in my soul for something absolute and immaterial.

- Words my mother gave me in my youth have echoed in the actions of others.

- She said, “Baby, living is something we do together.”

Donald Quist is author of the linked story collection For Other Ghosts and the essay collection Harbors, a Foreword INDIES Bronze Winner and International Book Awards Finalist. His writing has appeared in AGNI, North American Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Rumpus,and was Notable in Best American Essays 2018. He is creator of the online nonfiction series PAST TEN. Donald has received fellowships from Sundress Academy for the Arts and Kimbilio Fiction. He earned his MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts, and is currently a Gus T. Ridgel Fellow in the English PhD program at University of Missouri.