You need a car to survive in L.A. You can’t get anywhere otherwise. This is accepted as a fact, but it’s only half-true.

I grew up used to walking from the bus stop to the grocery store via the parking lot, because cars come first in this city. Today, I still bob and weave through parking spots, slipping in between cars gleaming in the sun, shielding my face from the rays coming down, hoping no one accidentally hits me as they’re backing out. I might pretend, perhaps, that I just parked my car, too. That I’m carrying my grocery bags to the trunk, overflowing with the things I still haven’t taken to the thrift store and the picnic blankets I forgot to take out.

I check the road before I cross because that little figure blinking “yes, you can go” knows absolutely nothing about the lawlessness of L.A. drivers. I never take my first step onto the crosswalk without looking both ways; cars sometimes take traffic lights as mere suggestions. Sometimes they brake abruptly, annoyed someone got in the way. This is the city of cars, not a land of pedestrians. Get used to being one step ahead, and jaywalk only when the coast is completely clear. Know that the sidewalks accordion in size, some roomy enough for two people and others barely wide enough for one. These are the bits of knowledge I carried with me into adulthood.

The people on the buses and trains become invisible this way, since L.A. is often chalked up as the land of hunks of metal, road rage, and bumper-to-bumper traffic.

Taking public transportation requires getting to the stop on time and walking the distance that might be left over. Without a car, a trip to the grocery store to get ingredients for dinner, the post office to mail bills and work on Monday becomes harder.

According to a KCET article from 2018, 4.5 million people “walk, bike, drive, rideshare or take public transit to get to their jobs.”

Nobody walks in L.A. Another lie.

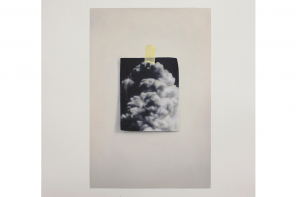

In the short film “Last Light,” Carmen Argote layers the sound of her voice over footage of Los Angeles in the midst of quarantine and stay-at-home orders. In this dystopian and empty environment, she seems to be leaving a voicemail for someone, or perhaps recording an audio note to send later. We watch her walk around the city and take in the passing cars. Curls of smoke from an unknown source, just off camera, bring to mind the recent uprisings.

At the beginning of the video, a black-and-white view of palm trees and skyscrapers fills the screen. Then, a digital figure whose legs are moving, the countdown underneath. The walking sign indicating that it’s okay to cross. This quotidian sign is made unnerving as Argote says, “I almost died.” We see the artist wearing a face mask. We see the empty highway.

And then, a view in full color of Argote’s feet on the road, a contrast to the black-and-white shots of her before. “Moving within the city, there’s just not very many people,” she says. But she’s there, walking. The digital figure becomes human.

The beeps of the crossing signal are familiar to anyone who walks often. Like other morsels of information that become part of the routine.

I know to look out for the sharp peaks in the concrete that get shifted by tree roots. I walk to the rhythm of the music from portable speakers that people carry on their bikes or in their bags. I start to notice which blocks are clean, versus which ones have trash lining the gutters. I learn to get used to the sound of my own steps, my heels against the concrete or the soft padding of my sneakers. I recognize the swish of my pant legs when I walk briskly. I pinpoint people’s steps behind me or their shadow across the wall before they even get close.

In cars, you whiz past these details. On the sidewalks, there’s no escaping them.

Argote says she can hear the sound of each car and every bird, amplified.

Walking in quarantine brings up childhood memories for her. When she was a kid, she remembers walking carefully to the other side of the street, subtly, to avoid gang members. So that they see through her. So that she doesn’t walk into trouble.

Now, we avoid crossing paths with one another for fear of catching each other’s germs.

Sometimes I cross to the other side of the street when I see someone walking toward me. Or I walk into the street a little, turning my head to see if I can buy some time from the cars zipping past.

It’s a game of chicken: who will cross first? Who feels more afraid?

Argote documents her walking journey, like the way you would give someone driving directions. She points out the streets she’ll take, her hand in a disposable glove as she drags her pointer finger along those little black dots on the sidewalk to mark each location, the ones that look like paint splatters on the concrete. Her finger grazes from one to the other, each dot standing for the next destination. She talks about how Mission is a long street with glass repair shops. These are the landmarks she sees when her feet take her down a familiar path.

My mom was heating up Thanksgiving leftovers when she started getting labor pains. A few hours later, she decided to take a walk to ease the pain from her contractions, but it was strangely, aggressively windy outside. She held onto her coat and tried her best to walk anyway.

The walking, she hoped, would help with the contractions. I imagine her petite frame, tracing and retracing her footsteps on the sidewalk.

By the end of the video, when the sound of the cross signal breaks the soundscape again, the sidewalk beeps sound more like the tempo of a heart rate monitor. Mortality made clear by a pandemic, made clear by walking.

I move to another part of the city. There are so many people walking dogs. One night, the lights from the car illuminate two figures in my new neighborhood in Mid-Wilshire—two women walking a dog, casual. I look at my phone: 8:58 p.m. I’m shocked they’re out this late.

They’re walking at a leisurely pace. Their shoulders aren’t tense; they’re not thinking about who might be coming up behind them. Growing up in South Central, I understood you walked to get somewhere, not just to take a stroll. My mom and I often walked to the corner store. We didn’t linger after buying our pound of meat and the bag of chips I pleaded for. We headed straight home. In South Central, most people keep their heads down when they walk. And it’s a given that you don’t walk around alone after dark.

At the same time, I found unexpected kindness on those often-volatile streets. Strangers who gave me kind words or people who waved as they watered their front lawns. Driving means you can stereotype South Central, walking means you have to actually see its residents as complex, real people.

Now, my mom’s blood sugar is high. She starts taking walks just in the front and back yard of her house in South Central, trying to get her steps up.

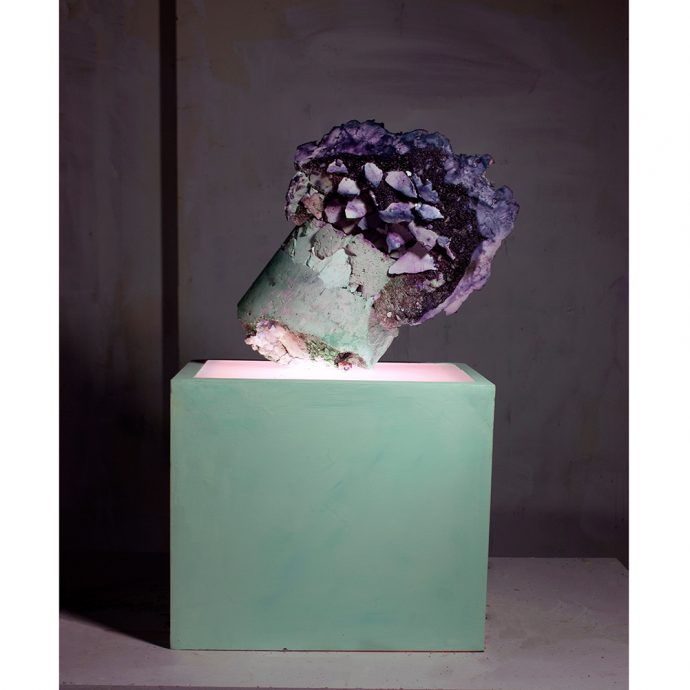

Argote plays with our perceptions of the city. The cars that we give so much importance to, the buses and trucks, she makes into tiny objects. Squeezes them between her fingers, still covered in disposable gloves.

The mechanical jaws of a construction digger look like the head of a prehistoric animal through her lens. She turns our view to the sidewalk, to the shadows from a nearby tree rippling on the concrete, broken up by the shine of passing headlights.

Argote’s empty streets are eerie. Many have lost the luxury to wander around the city. They want to get inside as quickly as possible. Walking, though, makes it so you see truths of the city, so that the invisible becomes visible—even if you don’t leave a mark yourself.

To pass the time when we walked, my mom and I used to race to step on the crunchiest leaves that we could find. We’d giggle when one was even louder than the one before. The flattened leaves, swept away, were the only evidence of our presence.

Towards the end of the video, Argote says, “I don’t think we can go back to the way things were.”

Walking lowers my anxiety, so I download an app and set a daily goal. When I hit my step goal, it vibrates with virtual confetti.

But then I get anxious about getting too close to people.

I get a physical and the doctor says my blood sugar is high and that I need to exercise more.

So I walk because I need to, for my own health, but walking is dangerous, since we’re all trying to stay away from each other. Is this another way opting to drive in this city might help someone survive?

Those of us that have always walked will keep walking.

Eva Recinos is an arts and culture journalist and creative nonfiction writer based in Los Angeles. Her essays have appeared in Electric Literature, Catapult, PANK, Blood Orange Review, Dryland, and more. Subscribe to her monthly newsletter for creative, Notes from Eva, at evarecinos.com.