from hella

Since Lulu told me that she liked girls, a lot of things had changed. In the past year, she’d moved a few times. Her newest place was a third-floor apartment on the corner of Haight and Steiner, in The Fillmore. When it came to thugged-out reputations, The Fillmore was up there with Hunter’s Point and Sunnydale. Even though Lulu didn’t live in the projects, the ‘jects were just two blocks down the street. The neighborhood didn’t seem all that treacherous to me, and Lulu’s new address improved my reputation with Clarinada. When I’d come back from weekends with Lulu, niggas would ask me where my mom stayed at in the city. When I’d say she stayed in The Fillmore, they’d nod with approval.

To celebrate my upcoming birthday, I got to spend the weekend with Lulu. My grandmother had started letting me take BART into the city. She’d drop me off at the Daly City station, then Lulu would meet me on the other side at 24th & Mission. I’d ride the escalator up and catch Lulu tucking a finger into a paperback book as the crowd of commuters fanned out into the neighborhood. Lulu would see me, and her cheeks would brighten. She’d pull me in for a hug, and the sweet musky scent that filled my nostrils wasn’t perfume or cigarettes or anything else but my Mommy. The sides of her head were shaved, and the short hairs scratched my cheek. She wore a pair of dirty red high-top Chucks, cuffed Levi’s, and a satin bomber jacket. She was a connoisseur of second-hand bags, backpacks, and knapsacks, and as our hug dissolved, she tucked her paperback into the belly of an old leather satchel I’d never seen before.

“How you doing birthday boy?” This would be the last time she was taller than me. We saw each other every couple months, but sometimes the gaps were longer. There wasn’t a set schedule. I visited when she wanted me to, when she had time. I wanted to see her more, but I’d learned not to bug her about it. She worked a lot, and when she wasn’t working, she was demonstrating, marching, or doing something else political. “I don’t have a car. It isn’t easy,” she’d tell me. If I got bratty about it, she’d shoot me a glance that let me know I’d better stop. She never struck me—she never had to—her disapproving look was enough to make me behave.

“Come on, we’re gonna head to Union Square and get you something for your birthday.” She took my hand. We weaved through the crowd, aiming for the MUNI stop. A bunch of fools were hanging out in front of McDonald’s, clowning, talking shit. Latino, black, and Pacific Islander, teens who looked like Clarinada. They sported the same starched Dickies and striped Ben Davis shirts, the same Starters and Derby jackets, the same flat-billed baseball caps. They passed around 40s in brown paper bags, shared thick brown blunts of weed. I could smell the dank smoke as we passed. Whenever I saw dudes like this in the city, I’d study. I was careful not to stare or make eye-contact, but I’d register how they walked, how they scanned the streets like they were looking for cops or fools trying to run up, how they fell into one another when they laughed. Ray or LaMonte or any of the Clarinada heads could’ve been dropped onto these corners and fit right in. I was getting there.

The sun was setting and neon lights snapped on all over the place. Orange and white MUNI buses coasted along, attached to floating electrical lines, buzzing and launching sparks into the air. Lulu and I climbed onto a bus, making sure to take the flimsy paper transfers the driver offered. Lulu nodded for me to slide in beside the window, and she dropped into the aisle seat. The bus lurched forward. She took my hand in hers, measuring my growth against her own fingers. She did this every time we saw one another. Our fingers were remarkably similar, though mine were still a bit shorter and a few shades darker. Lulu sighed, raised her eyebrows. “Getting too close there baby boy,” she said. “Don’t.” We smiled at each other. She leaned against me and slipped her arm through mine so that we were linked at the elbows, hooked. The pressure was nice. I turned my attention to the window.

I loved rolling through the city and seeing all the graffiti. Bus shelters, phone booths, newspaper bins, billboards, walls all drowning in tags and throw-ups. In this era, in 1990, I had a front row seat to the work of future legends. TWIST’s tags and throwies were everywhere, along with his cartoon-like characters: the screws, the clocks, the sad faces. His work made vandalism look fun. Most of the writers seemed to roll in pairs. I’d always see DUG and GIANT tags up in the same spots, side by side. Same with KR and REM. REM’s horses galloped across boarded-up buildings and along the edges of MUNI tunnels. Later, when I learned that REM was a girl, and that her full tag was REMINISCE, I thought that was cool, that a girl was out there bombing as hard as the dudes. That was tight.

At Union Square, me and Lulu got off the bus along with everyone else. She was a fast walker and expected me to keep up. I had to acclimate to the speed and pace of her city rhythm.

“You remember where I work?”

“Saks Fifth Avenue.”

“You see it up there?” Lulu pointed across the busy square, at the five-story department store on the corner, just beyond the workers putting up Thanksgiving decorations. I grunted as she guided us toward a Bank of America. “I’m just going to get some cash out, then we’ll find you a present. We’ll go there first because I get a discount. But if you don’t like anything, we can go someplace else. Okay?”

Lulu slipped her card into the ATM. A line began forming behind us. She clicked through menus, groaning and sighing, punching the keys harder and harder. “I don’t know what’s going on.” I turned and looked at the screen just as she hit the BALANCE button: $1.16. I didn’t know much about money, but I knew that was bad. She yanked her card, took my hand, hissed as we stepped aside. We walked away from Saks Fifth Avenue. Away from Union Square.

“Got your transfer?” she asked. I held up the scrap of paper. “Okay,” she said. Back on the bus, Lulu explained that her credit card wasn’t working. Her face was tense, her eyes focused. She looked like me whenever I tried to do math. “I just got paid.” She shook her head, confused. I could see that however bad it was for me and grandma back home, Lulu was having just as hard of a time in the city. “Anyway, I have some cash on me. Enough to get us through the weekend.” She draped an arm around me, pulled me close. “Pizza?” I nodded. “Movies?” I nodded again. “We’ll stop at the video store on the way home,” she said. “Then tomorrow we’ll look at the paper and see what’s playing in theaters. Okay?” I nodded with the casual confidence of a spoiled kid because that’s what I was. Or had been for a very long time anyway. But like I said, a lot of things were changing.

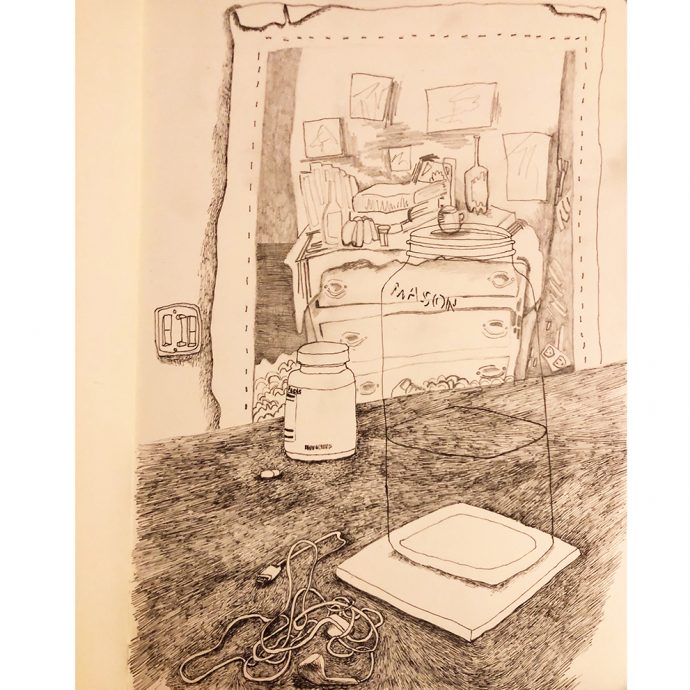

Waking up, I adjusted to the fact that I wasn’t at home but in Lulu’s living room on her sofa. Her world was blurry without my glasses, and I liked that. The weight of the thick comforter was cozy. I could feel the San Francisco cold on my face, but I was warm.

Lulu called, “You up?”

In the kitchen, she served up breakfast. Inside a gray sweatshirt that had reached the pajama stage of its life, she slid from the stove to the refrigerator and back again, her slippers making that whoosh-whoosh sound with each lunge. Her buzzcut was a wild corkscrew. Her face puffy. And her plaid pajama bottoms shifted loosely around her skinny legs.

I sat down at the dinette table. Lulu gulped coffee loaded with cream and sugar. I had orange juice. We stuffed the eggs and bacon and buttered toast into our mouths. We didn’t talk about Grandpa, but he was there. Lulu made breakfast the same way he did, and we treated the consumption with a sort of silent reverence. He’d been gone for five years, but the collapse of our family had happened in slow motion. His death had wrecked each of us in different ways, gradually, like the cancer that had ravaged his lungs. Between bites, me and Lulu smiled with oily lips. She flipped through the Chronicle’s Pink Pages and read our horoscopes.

I folded my blankets and tidied the living room. When Lulu called out that it was my turn, I showered. When I walked out of the bathroom, I smelled cigarette smoke, then heard a new voice. There was a woman I’d never seen before sitting on the sofa beside Lulu, close, my mother’s arm around her. The stranger was strumming a guitar.

“Here he is,” Lulu said, turning, looking at me. “Damien, this is Linda.”

Linda pulled a cigarette away from her mouth, blowing a smoke-stream into the air. Her chapped lips slipped into a smile. There was a twinkle in her eye. Some sections of her straight black hair had been twisted into loose dreadlocks, and she wore an old, black top hat. Her eyeliner was heavy and smeared. Chunky silver rings covered her fingers and leather necklaces dangled down her chest. Her black shirt was raggedy, decomposing, on some zombie-type shit. She extended her hand. “Hey, kiddo.” I wanted nothing to do with her, but I shook her hand. I could see her black lace bra, her heavy tits.

“So, it’s your birthday, huh?”

“Thursday,” I said.

“Cool. Happy early birthday.”

I thought about if Ed were here. We would’ve clowned on her for looking like a crackhead. I stuffed my dirty clothes in my backpack. Linda plopped back onto the sofa, resumed plucking at the instrument. Her beat-up guitar case flung across the neat pile of my just-folded blankets.

“Linda’s going to come to the movies with us,” Lulu said.

“Yeah, I was thinking Troll 2. It looks horrible!” She had a villain’s laugh.

I felt Lulu’s eyes, looking for my confirmation. I kept my eyes down.

“Damien wanted to see an action movie. Marked for Death. Steven Seagal.”

“Steven Seagal?” Linda laughed, coughed a cloud of smoke, and kept at her guitar. That was a no, I guessed. I glanced at Lulu. She frowned and tried to read me. I walked down the hall, shut myself in the bathroom. I was salty as hell.

Before, Lulu had been in a relationship with a woman named Niki. I knew Niki well. The “gay parade” flag that was so familiar to me lived on the dashboard of her red Mercedes convertible. Niki spent Christmas at our home in Daly City. Pictures were taken. Both of them wore billowing silk blouses buttoned all the way up to their necks—Lulu’s red with tiny Christmas trees, Niki’s black with white polka dots.

Niki was mixed like me. We shared the same skin tone, the same soft curly hair, and that was enough for me to look at Niki and see someone I could identify with. That was an uncommon feeling for me. I liked it, and I liked Niki a lot. She was soft and welcoming whereas Linda was severe. It was only a first impression, but Linda wasn’t like me or Lulu. Everything about her—the clothes, the hair, the laugh—was extreme. A couple years later, when the 4 Non Blondes song “What’s Up” was one of the biggest songs on the planet and Linda was MTV-famous, I’d remember our first encounter with amusement. But on that day, my birthday, I just wanted to spend time with my mother.

During the Niki years, Lulu had a two-bedroom apartment on Ramona Avenue, in the Mission. Fashion magazines were always scattered all over the apartment. Niki was a model. She had that kind of look. Whenever me and Ed found Niki in the ads for clothes or makeup, we’d nudge each other and whisper excitedly. The four of us would often hop in Niki’s drop-top Benz and drive to Embarcadero to skate. Me and Ed would glide across the red bricks and concrete sidewalks, ka-click, ka-click, ka-click—the sound of EMB. Niki would stand on my deck and hold my hand, nervous, as I guided her around. Lulu would snap photos, one hand playing with a dangling earring, smiling behind her shades. I didn’t know they were a couple then. They didn’t act like girlfriends. They seemed like homies, like me and Ed. Movies at the Kabuki 8. Picnics in Dolores Park. Marches in the Castro. We tagged along wherever they went. They did what we wanted to do. It was chill. And then it was over.

From inside the bathroom, I could hear them arguing. It didn’t last long. In a fight, Lulu was more inclined to shut down than explode. The front door slammed shut. Linda’s combat boots galloped down three flights of stairs. When the lobby door closed, the whole Victorian shook. Lulu knocked on the bathroom door. “I’m gonna wait right here until you come out,” she said. I was embarrassed. I was acting like a baby, and I knew it. But I wanted to be more important to my mother than her new girlfriend. Now that Linda was gone, I regretted storming off, putting Lulu in this position. Slowly, I opened the door. She was sitting with her back against the wall, her face wet. “You okay?” she asked. I nodded. She dragged the back of her sleeve across her nose, sniffing back tears and breathing deep. “Come on then. Let’s get some fresh air.”

We marched up Haight. Whenever I fell behind, she’d stop near the top of whatever hill we were climbing, turn, and look at me. I felt like a burden. I hated that look. It was ten blocks from The Fillmore to the Lower Haight. We didn’t talk the whole time. When Lulu was upset or angry, she got quiet. And when she got quiet, I disappeared inside my own head.

Once the hills plateaued, we hit the busy part of Haight. Lulu stepped into a used bookstore and nodded at me to follow. I hovered near the front, spinning through the comic book rack as she moved up and down the stacks. She reappeared at the cashier, peeled a five from her thin wad and paid for a used paperback copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Handing me the book, she said, “You have to learn about yourself. I can’t teach you everything.” Outside, she draped an arm around me. “Listen,” she said, “you can be mad at me, but you can’t not talk to me. Okay?” I nodded, but didn’t know what the fuck she was talking about. I felt like she was the one who was mad at me.

She must’ve felt guilty because we ended up at McDonald’s. She dumped both of our large fries into the brown paper bag, seasoned it with salt, gripped the top, and shook it like crazy. She set the grease-stained sack between us, rolled the sides down, turning it into a basket. “I had no one to talk to,” she said. “And I’m still learning about myself, figuring my shit out. It’s not easy, you know.”

Sometimes my mother was my mother, and she was scary. Other times she was my friend, and she was fun. It was the moments that were in between that confused me. She’d unleash monologues where it felt like all the information required to understand what she was trying to say had taken place inside her head, before she had started speaking out loud. I was always having to catch up. “Look around,” she said, jutting her chin at the windows. Her eyes leapt from billboard advertisements to movie posters on bus stop shelters. “Those are all straight people, straight couples, men and women. You see that?” I nodded. “But I’m not like that. Okay? And you’re gonna have to get used to it.” Her eyes bulged a little as she studied me. It was in these moments when she wasn’t my mother or my friend that I sometimes thought she hated me.

I didn’t have anything to say. In a few hours, I’d be on BART heading back home and this birthday would be behind me. Pushing some fries into my mouth, I fanned through The Autobiography. I saw the words “pimp” and “hustler” and thought that was promising.

“There weren’t any examples for me,” Lulu said, “but there are for you.” She nodded at the book in my hands. “You can read. You can figure yourself out. Better than I did anyway.”

I looked out the window, at the skaters and hippies and thugs and regular-ass people walking up and down Haight Street. I wasn’t too sure she was right about that.

A 2020 PEN America Emerging Voices Fellow, Damien Belliveau is a native of the San Francisco Bay Area and a veteran of the United States Army. He has spent the past 15 years telling stories in the world of reality television as an editor and director. The founder of The PartBlack Project, a Q & A photography series documenting ethnically mixed people like himself, Damien is currently revising his first book, hella.