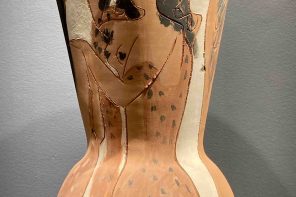

I come from a lineage of cotton. Of the genus Gossypium, of fabric pulled and spooled by working hands between the Río Grande de Santiago and the Río Balsas over half a millennium from now. Of plant guts plucked by scarred and sun-drenched African hands—hands that have forgotten what home feels like—picking out my seed. Of the hands of an Aztec woman, wrapping, spooling, white string wrapped around her body as a fulcrum, her body a machine, creating me in a dance, spinning and spinning and spinning until I am not Gossypium but fabric—rich, soft ichcactl: cotton.

I am the very fabric of nature.

The best part of my day is you. I like when you come home to me, cocooned into my fabric, a caterpillar burrowing into itself. I do what I am created to do, and that is to make you comfortable. But you don’t know any of that. You just know that I am warm and you are tired. I smell like you, underarms, toothpaste, shampoo.

I’ve known you since you were a child. Swaddled within baby blue cotton, passed down from your great-aunt Wilma, and then, I held you as your mother held you in her careful arms. Your limbs grew seemingly overnight. I wrapped the smoothness of your baby skin, fresh from a bath in the kitchen sink. And when you outgrew the sink, you followed me into a new bed, one that your mother bought from the Disney store in the mall¹ after she got the promotion at Boeing.

¹Disney’s cotton comes mostly from India, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan. Your first big kid bed sheet comes from Uzbekistan. A woman named Gabriella Ivanova slings a fabric sack full of freshly picked cotton across her back. The sack topples with cotton and looks as if it were a giant bag of snow. She walks down rows of cotton fields, stooping to pluck. There’s an ache in the stoop of her back where her muscles have seemed to remember the weight of the sack. She imagines the inside of the factory looks like it is covered in mounds of snow. The piles of cotton seem to extend upwards for miles, mountains and hills of white, ever tumbling. She dumps the sack into a green truck, and at the end of the day, she watches as the truck drives away, out of sight. The truck clunks into the building she’s never entered.

You got the princess bed—fleshy pink with pure white ruffles—the kind you begged for, even threw a tantrum and, simultaneously, a plate of meatballs right on the lampshades. You cried for me. (At least, another version of me, as every stitch of cotton is both we and I.) You left your tears on your mother’s cashmere sweater.

When you were four years old, you cried when your father overdosed on propranolol and when you heard the doctor say that it not only lulled his heartbeat to a slow nothingness but left him, stunned and stilled, with cotton-mouth, you thought his mouth had turned into cotton. And that was the most terrifying of all – that a human could one day not be a human. That your dad could one day not be your dad.

You’re a teenager now. You’ve just turned 13. And you don’t know how to articulate it, but you expect to get what you want. You’d never say that, though. Not out loud. You mean well. You can’t help but remain in a default setting where everything revolves around you. You are, after all, only able to know things from your own perspective. And you know a lot, don’t you? You know that there are roughly 15 to 20 little hairs right beneath your pubic bone. They feel like wool. They curl in on themselves, like they’re ashamed of their rough, wiry texture. They feel coarse, uneven, otherworldly. Monster, like an old hag in a fairytale.

And if that beast, you’re guessing, the one that lives inside you now, had a face, it would look like those hairs. It feels like you, but not quite. Maybe a deeper, more sacred you. You’re afraid of her. How she claws herself out in your dreams. Now, your dreams are all hot lips, moist bodies pressing into each other, pushing and pulling with bare open hands, an impossible fullness. They fill with the sound of entangled limbs gliding apart and back again like citrus fruit unpeeling, the way nature had already preordained. Somewhere between consciousness and not, an explosion that starts in the deepest parts of your belly, ricochets up and around to the tips of your toes and tingles your scalp, awakening a sensation too good to be holy. You wake up, damp, panting, aware of a foreignness of your body, of a deep-seated relief. You know that there is something, a warm and wet something, pooling to the side of your thigh, thickening. You feel it cool and stick in your underwear, the kind that your mom picks out in a pack at Walmart, as you let the sun rays from your blinds warm your exposed belly. You listen to the birds chirping, and the newest pop singer blares song lyrics about parties from your alarm clock before you slam the snooze button.

You smell funny. You can’t describe the smell. It smells like shame. And if shame had a smell, it’d smell like the way you feel when you wake up from these dreams and your eyes flutter to the Jesus crucifix, the one that your grandpa drilled into the wall when you were an infant.

You just know that you smell Her—the old hag, not Jesus—in your sheets. And no matter how much your mother tries to wash out the smell, it still lingers. She’s noticed. She isn’t disgusted, just aware that her daughter isn’t a child anymore. She knew that when you stuffed bloody sheets in the back of the closet, and now you’re aware of the power of dish soap and bleach. She’s noticed how your temper flares, when you pour your skim milk into your cereal too fast, dairy sloshing onto her granite counter. Slow down, she says. You grunt in response and slurp your breakfast without a spoon, a Neanderthal, barbaric, un-ladylike. Jesus fucking Christ, she whispers then apologizes to Jesus. You turn away from her disgusted scowl, wipe the milk from your upper lip with the back of your arm and she notices, again, that you’re not a little girl. Not the way your chest expands against your cotton T-shirt² and your collar bones peak out like a newborn butterfly wing.

²Hanes: the kind that comes in a 6-pack at Walmart. She’s tried to switch to an alternative eco-friendly brand after her friend, Betsy, at the gym, said that Hanes has sweatshops in Asia. This particular shirt was handled by a girl named Yang Jin. She works twelve hours a day, Saturday and Sunday, to support her family in Gansu, China. Her feet were in poignant pain that day, enough so that her toes finally succumbed to the pressure riding against her arches and went numb. She was thankful for the nothingness, at least until she had to walk to work. Màn zǒu, literally “walk slowly” but meaning “take care,” she hears her mother say to her grandmother before she leaves the house in the morning. She can’t help but scoff at the irony as she sits on the edge of the bed, stuffs in her shoes the leftover gutted cotton strips from the rare malfunctioning machines. They comfort her as best they can, offering minimal relief every step of the way. When she arrives at work, your shirt, the one you’re wearing in the kitchen, is the first one she cleans and she snips a loose thread along the neckline. Clean, concise. The sharp snip sound of scissors snapping starts to lull and fade against the ever-present whirring of spinning textile machines. She begins to wonder if she, too, is a machine. Tomorrow, she turns twelve. Under her breath, happy birthday.

Your mother watches you, a little afraid, a little apprehensive, the way a driver watches a deer on the edge of the highway. But you don’t run, not like those other kids on the nightly news who carry bullets in their utility vests and wait for the perfect day. You’re a girl, anyway, and that’s what boys do.

Your mother hears the rattle of pills in your backpack. She checks your nightstand every night and counts out the orange pills. She notices you’re anxious now. How you jump at certain sounds or loud noises. She watches you grow, ascend past her height, tower tall enough that she has to ask you to reach the jar of jam on the top shelf. You’re all arms and legs, pillowy and soft. You’re not a little girl anymore. You grow out of your shirts and you replace me with a newer me. Plain pink sheets, not cartoon princesses and unicorns. Sophisticated. Womanly.

You’re 19 now—almost 20, an almost not teenager, as your black friend Jeremy puts it—and there’s a girl in your bed. Your mother doesn’t know that you’re into girls, but she has suspicions. She thinks it’s a phase. She had a phase like that too in college, but she’ll take that secret to the grave. The word “lesbian” has never been used in your household. It’s only whispered behind your back after Bible study. You’re hooking up with a girl named Shanice, but she goes by Shane because Shanice is “too black.” She wants you to stop referring to Jeremy as your Black Friend.

I have a white friend named Jeremy. He’s the black one. So, Jeremy. Black Jeremy.

Still.

It’s not racist. My great-great-great grandmother was black, I think.

Shane is the child of two Jamaican-born parents. Her hair is thick and full, usually pulled into a high puff, like a crown or halo. As the sun goes down, her hair rises, little spools of dark brown cotton spiraling towards the sky. You tell her that her hair reminds you of cotton.

Cotton?

Yes.

You’re lying on your back and her head is against your chest. It’s your favorite way to cuddle because you can feel her breasts on your stomach. You’ve seen them before, and you think about the first time you saw her naked, how her nipples were larger and darker than you expected, the way they fall submissive to gravity in your tiny, dank dorm room, and how she leaned down shyly, and crossed her legs crisscross applesauce at the foot of your twin size bed. You couldn’t tear your eyes away from her chest, how her areolas fanned out from the center of her breasts like saucers, and they immediately made you think of pizza sausage on two black plates.

She’s never told you this, nor will she ever tell you this, but she saw the way you looked at her that first night. How one glance told her who she was. But you weren’t disgusted, just curious, as you’ve never seen skin so dark and deep. Sometimes, you thought that you could fall into it, like a wormhole. She drapes her denim³ jacket over her bare body. She lets you dip your shaky fingers—did you take your medicine?—inside her and you curl up and out until she sees stars.

³A hand-me-down from her half-sister, Dawn. The jacket is made of 100% denim, pure cotton. The tag says it is from American Eagle. It’s worn down with age but also from a process called sandblasting, which involves abrasive materials propelled at high speeds. This technique also causes lung damage for factory workers and so has been banned in several countries. Except in China, where a man named Xi Wu, who was blasting silica on a mass of denim fabric in 2015, inhaled without a mask (the factory ran out of masks that day and could not get a shipment—for 20 years). Tiny colorless compounds of the rock shot directly down his throat. The death was not immediate, but gradual, a silent disease. The autopsy revealed the silica sitting like sandy stones in the canal of his trachea. The coroner stated during the inspection that they looked like a leaf in late autumn. Dead, but beautiful nonetheless.

Why cotton?

Because that’s what it feels like.

Shane never intended to hook up with a white girl from ritzy Greenwich but here she is. Wrapped up in your bed, she finds guilt in the fact that she enjoys the way that I smell like you. She doesn’t like you all that much because she thinks you’re a little dense, but she likes the attention you give her. She feels sorry for you because your dad died, but at least you have an excuse to be sad. Her father is alive but absent so he might as well be dead. She likes that even though your dad is dead, you don’t seem super fazed by it. It doesn’t seem like you have daddy issues. She admires that. She doesn’t know what that means about her.

My hair is nappy.

Haha . . . yeah.

Shane has always thought that the idea of being between the sheets⁴ with someone would be romantic, maybe even raunchy, but instead, now she’s just thinking about how much she hates her hair. How it spirals unruly, unafraid of nature or physics. She doesn’t like that it makes her think of cotton.

⁴“Between the Sheets” is a song by the Isley Brothers released in 1983. Before he left, Shane’s dad would blast this on his record player and force her mother to dance with him, right in the living room. He’d carefully place the record on the player, set the needle, and close his eyes as the piano synth filled the room. Then, he’d set the record cover back on the shelf, facing the room, showing off the album art of pink silk sheets and a red rose. Shane was four years old and thought those sheets looked so soft. She thought the song was about laundry. She thought the man’s voice sounded like a woman’s but in a soothing way as if a man and woman combined into something ethereal, angel-like. She watched her parents dance, swaying their bodies, a pendulum.

Shane looks at your bedside table. She notices that you take the same pills that your father overdosed on. You’ve offered her some before when she told you that she gets anxious before exams. She’s started taking them now daily. She steals them from your backpack. She took three just now, while you were in the bathroom, just enough to take the edge off of the pitter-pattering of her heartbeat.

It’s enough to sink her in a stupor. Not deadly. Just vacant.

A face blurs across her peripheral and for some reason, she knows it is an ancestor. The face, a phantom.

June 17, 1856

Your name is Chiamaka but you don’t remember it. Your slave name is Ruth.

Sweat beads down your back and drops down into the waist of your undergarments. You reach your hand into a bushel of us, pluck our seed. You’re used to the pain. We don’t relent.

A knock. You look up at the big white house and put a hand to your face to shield your eyes. The house stands like a fortress on the plantation. Master Timothy is standing at his bedroom window, his eyes locked on you. It’s high noon, the sun is in the sky, an angry ball of gas, and Lord, you need some air. Clean air. All you can think about is a glass of water and breathing in something that isn’t dust.

You straighten us on your hip, cradle us like a toddler. You look over at Jim who is throwing a rake to the earth over and over, his sweat-soaked shirt made of osnaburg.⁵ You’ve birthed five of his children. You often feel you’re not a woman, just a womb.

⁵A material made of linen, coarse and plainly woven, originating in Osnabruck, Germany, from which it gets its name. Osnabruck, famed for its linen production, fueled the slave industry until the industrialization revolution in Britain. This particular shirt, the only one your beloved, Jim, owns, was made in 1826 by Ida Weber, a weaver from Grambergen. She was newly married when she was weaving the strings that would soon be Jim’s shirt. She was bent over the power loom in the textile mill, a fetus in her belly that she didn’t know would be a boy. She was extra careful, since just the week before, she overheard that a woman, inexperienced, caused the weaving to jam, and the shuttle hit her in the face. Her cheek was bruised and blackened, ugly and unattractive. When Ida went home and told her husband about it, he said that he was glad that it wasn’t her, because he would not be able to kiss such a black face. She laughed and served him custard for dessert. Across the Atlantic, ships carried browned fabric to a fresh country called the United States.

You look back at Master Timothy. He crooks his head like a tic. His tongue licks at his bottom lip in one flicker. His nightshirt falls open, a thick curl of hair sprouting underneath the linen collar. Then, he moves the curtain and vanishes.

You place the basket on the ground and watch dust billow around your skirts. You feel the sweat pool in your underwear, lapping between your thighs, dripping from the fat under your buttocks. You stand stock-still, as if in a trance, between rows of cotton fields. A black crow caws and circles lazily. Heatwaves rise and sway like snakes from the white porch steps. Your feet take one step after the other, your eyes on the window, the curtain still swaying back and forth, back and forth. Like a fan, an invitation, a greeting.

Hello.

I am here.

Come in.

You walk behind the house and Jim looks up from his spot by the hay. He runs the back of his arm across his shiny forehead. Ruthie?

I’ma be back.

Up the stairs. Master’s wife gone. Turn the corner. Make a left. The door is already open. He’s already naked. He’s waiting. He blinks.

Ruth?

You want to say that’s not my name, but don’t. The name your mother gave you feels like a song. You don’t know the words, just the melody.

He doesn’t know your name. Not the one that matters.

You lay on his chest, listening to his heart sputter. He doesn’t have much time. He’ll die before fifty. His son will own you. But not right now.

He slithers a hand into your hair. Thinks about cotton. You feel his seed spread inside you. You’ve birthed five of his children and you will birth a generation more. You don’t know it, but you will have a high yellow great-great-great granddaughter who will allow herself, also, to be swallowed whole.

We sit in a basket outside and we spread our seed across the ground and allow the earth to swallow us whole. We’re shipped to Europe. We set on ships. We’re sold, exchanged, bartered, auctioned.

They dip us in dyes of red, yellow, blue, indigo.

We are woven with thread and made into flags.

We wave atop schools, buildings, organizations.

We hold newborns, new couples, new homes, new patients. We watch you sleep. We watch you cry. We watch you moan. We make your deathbed. We hold you in our arms and watch you come to life and watch you take your last breath.

You’re thirty now. You’re your mother’s age. You’re our age. You’re dust. You come from earth and back into it. You’re us now. You’ve always been.

Chelsea L. Cobb is currently a Creative Writing PhD student and graduate teaching assistant at the University of Georgia. She writes lyrical fiction and dabbles in poetry, often centered around Blackness, gender, and sexuality. Her fiction has won the Margaret Harvin Wilson Writing Award. Her work can be found in Stillpoint Literary Magazine, Buzzfeed, and elsewhere.