Cassandra stood above the man on fire. She had him laid out on the table in the center of the corner office, along with other photographs. As she circled them, deciding on their order, she rubbed her lower back absentmindedly. There wasn’t any pain there anymore thanks to the electroceutical, but, even so, she often found herself gingerly massaging that area, remembering the throb that was once lodged there.

His name was Thích Quảng Đức, a Buddhist monk who set himself alight on the 11th of June 1963. She remembered being shown the photograph in high school. It was the monk’s complete composure throughout his self-immolation—and the way the fire sprang from his flesh like a horned animal—that drew her breathless silence. Tony had pulled up the photo on his phone at second break, near the tennis courts, and that day she went home to read up on eyewitness accounts of June 11th. A line from David Halberstam, a journalist, stood out to her. Human beings burn surprisingly quickly, it read.

The monk’s photograph would be one of the last in the series, she decided. It would go next to an image of white crosses stuck askew at the bottom of a barren hill. This photograph, shot decades ago in Marikana, was a reminder to her of the claw-and-dagger place the world had once been. It was a story of men being sent into Earth’s airless belly and returning to the surface with a wheezing desire for a bigger share of the sun. And then, being swatted away like flies, those men had had their bodies pulverized and pressed into the crust of the Earth, permanently.

Images like these didn’t fare well with the public. The wide-spread adoption of social cohesion electroceuticals made the museum’s exhibits superfluous, according to the Department of Happiness. Still, Cassandra was grateful for the invention of the small, cranial implants, made up of hundreds of electrodes packed into a few cubic millimetres that, once implanted, listened to the oscillations of an individual’s neural network in order to rapidly pinpoint the emergence of sick circuits that could be altered before they caused further distress.

Cassandra had succumbed to a sick circuit back in university when, after a long night of drunken partying, she fell down a flight of stairs. Her back injuries resulted in months of achingly intense physiotherapy. Even after the muscular tear had healed, the discomfort in her lower back remained. Like a never-ending echo of a scream. The pain-memory prevented her from sitting in hard plastic chairs or doing back-bends in yoga, or even from being held passionately by a would-be lover on a strobe-lit dance floor. When medical experts began touting the ability of electroceuticals to rewire pain pathways in the nervous system so that overstimulated neural patterns could be downregulated, she was eager to suture the chasm that had emerged between her body and mind.

Hey Cass. How’s the selection going? A voice note from Audre got fed through the speakers of the office. It was four in the afternoon, time to knock-off.

“I just have to pick a few more and we’ll be ready. Send message,” said Cassandra out loud.

Are you a hundred percent sure about this? was Audre’s reply. She left Audre’s question unanswered, sliding the photographs back into their plastic sleeves and locking up her office.

Whenever she took the bicycle lane past the Department of Happiness Cassandra would stop, briefly, outside the mammoth glass building to see how many people were sitting quietly in the lobby, waiting for their name to be called. The department provided in-depth life narrative analysis for all citizens. Using its vast archives and teams of researchers, it annually produced thousands of life reports: detailed leather-bound journals that documented the exact steps an individual should adhere to for maintaining optimal happiness. It was obligatory for every citizen to receive such reports at the beginning and end of every decade. Every report came with a barcode that, once entered into a vitality keypad, provided the recipient with enough capital in one’s vessel account to sustain themselves as they worked towards the goals outlined in their life report.

Cassandra balanced herself on her electric bicycle with one foot on the curb, the Department of Happiness meters away, and checked her wristwatch to see how much she had left in her vessel account. It was enough to see her through the museum’s closure. She knew she would have to go back to the department once the work at the museum was over in order to get her new life assignment. Something inside her dreaded going back. Though the building was an architectural marvel—made to look like a giant glass egg, its outer panels refracting sunlight into rainbows that streamed across the walls of the lobby—she couldn’t bring herself to sit docile in the queue and watch the same nature documentary on the monitors that had been showing since the department’s inception. The documentary, Unicellular Saviour, was the poster child of the post-climate epoch. There was hardly a person alive who hadn’t watched the story of how the engineering and wide-spread distribution of a bioreactor, fuelled by a strain of algae called Chlorella vulgaris, added an extra fifteen minutes to the doomsday clock by soaking up billions of tons of CO2 from the atmosphere, while simultaneously providing barrels of biofuel.

When, at dinner parties, she tried to bring up her hesitancy over going back to the department, she always got the same reaction. Thinking about it now, she imagined superimposing her friends’ surprised faces onto those who had witnessed the death of Thích Quảng Đức.

Yes, she thought, their faces would fit right in.

She’d been living with Tony for three years. Their apartment was opposite a newly opened electroceutical surgery that was busy six days a week. Tony worked at the surgery’s reception. He really believed in the work the new technology was doing, never wasting a day to report to Cassandra about another success story.

“We’re featuring this rehabilitated coke addict on our website next month. Cass, it’s such a breakthrough for this patient. They have been to psychotherapists and some well-known clinics, but nothing has killed their craving like our electroceutical. They’re practically a new person,” said Tony, pouring wine for Lebogang, Keano, and Aanya.

Cassandra listened as she ate Lebogang’s shitake and kale pasta, secretly craving a toasted bacon and egg sandwich. Tony was the on-the-go type, always with an eye for the next big thing in tech. If it wasn’t for him, Cassandra would never have known so much about the science behind electroceuticals. Though she never mentioned it to him, she admired how much faith he had in technology. Her faith never moved past agnosticism, though she couldn’t deny that when technology worked in humanity’s favor she felt her commitment to faithlessness waver.

“Tell me again babe, how does it work?” Keano asked Tony, leaning his head on Aanya’s shoulder. Aanya played with Keano’s curly hair with one hand while twirling Lebogang’s pasta around in her bowl.

“Well, in layman’s terms, the implant detects the rising of a craving in the reward centers of the brain. Then through electrical stimulation, or inhibition, it squelches the neural pattern that’s driving the addiction,” explained Tony.

The rest of the table looked at him blankly, but Cassandra had already heard this explanation many times. “Think of it like this,” she said, “if our behaviour is patterned by the firing of specific neurons in their distinct, synchronised way, then each time a pattern of neurons fires one after the other it sort of codes for the behaviour, or the memory, or the feeling. Right, Tony? Is code the right word?” asked Cassandra.

Tony beamed at her. “Someone’s been listening,” he laughed. “But that’s pretty much it. Think of the brain like a massive orchestra playing a symphony while following multiple conductors. The trick with electroceuticals is that they tone down certain conductors over others. So, if some musicians are stuck playing an allegro movement, then the electroceutical reminds those musicians of other, slower movements they can play, or directs them to follow a different conductor.”

“Keano should buy one for his neighbour,” said Aanya, clearing the table. Keano got up to help her while Lebogang shifted over to where Tony was seated. Tony kissed her, their tongues lingering in each other’s mouths. It didn’t make Cassandra uncomfortable; she was accustomed to the four of them being intimate like that. They called themselves a community of love and would often proposition Cassandra to join them. But, for her own reasons, she preferred living on the outside, looking in.

“What’s up with your neighbour?” asked Cassandra, getting up to help with the dishes.

“Oh Jehovah, he’s a dying species, that man. Believes in the missionary position and the sanctity of procreation over anything. And I mean anything,” said Keano.

“Geez, people like that still exist?” Cassandra thought of her great-great-grand-parents, wondering whether she should find out how they were doing. It didn’t take long for her to decide against that idea.

“Believe it, girl. But you know, I feel sorry for him. No part of the world he’s lived his life in is left intact. That kind of boundless creativity that touches everything, even sexuality, scares these uncles,” said Lebogang.

“It’s like the games kids play in sandboxes. When you change the rules mid-game it’s enough to get anyone’s back up against a wall,” said Aanya, holding Lebogang’s waist and swaying to the jazz music playing in the background. Cassandra wondered whether her museum was an outdated sandbox. Was that why it was being shut down? She had been meaning to tell Tony about the closure, but it was hard to get him alone these days.

“I’m gonna run a bath. It’s been a killer of a day,” she said.

“Go ahead babes, we’ll clean up,” said Tony.

It was a few minutes past midnight. The community of love had decided to sleep over at Keano’s. Cassandra appreciated it when they left her alone in the apartment, but this was the wrong night to be alone. Thoughts about the museum’s closure and the conversation she’d had with an official from the Department of Happiness circled like mosquitoes around her head. The official, a peacock-looking woman, informed Cassandra that the department’s nation-wide implantation of an electroceutical designed to “heal inter-generational scars on the nation’s psyche” was picking up speed. It had been decided that the museum’s archiving directive would no longer be required.

This “social cohesion project” would, according to the official, render museums like Cassandra’s no longer a viable way of engaging the past. “The past has too much emotional baggage anyway. And this nation-building electroceutical is all about giving our country’s collective memory a good spring cleaning,” said the official.

Cassandra recalled how powerless she felt in the air of the peacock-woman’s certainty. Lying in bed, she replayed the scene in her head, watching herself walk the official out, down a long corridor of granite sculptures of liberated slaves, past multimedia installations of mothers keening at the feet of police officers and a wall-sized painting of different species of birds perched on a wall of barbed wire that dripped blood and sinew.

Cassandra turned over in bed trying to shake the memory loose, but she only managed to fall asleep when the visual of the official, smiling widely and getting into her car, blurred and blackened in her mind.

Three months passed. Most of the museum’s artifacts were in the process of being transferred overseas to the few countries that kept their museums open, for the time being. Cassandra stood at the window of her office that overlooked the street and watched the robotic sweepers glide up and down, cleaning a pavement that was already grime-free. Across from the museum, a large electronic billboard advertised, in bright neon-purple letters, the nation-building project of the Department of Happiness.

An electroceutical for every citizen.

Do the right thing. Protect your neighbour.

Heal yourself. Heal the world.

Sign up! Never feel overwhelmed again.

Cassandra looked beyond the billboard, resting her eyes on the skyline, which was made up of a labyrinth of reinforced glass interspersed with solar panels. These days, entire skyscrapers had been refashioned into high-rise, botanical forests; greenery bloomed from out of every window, and when great gusts of wind swept through the city whole buildings rustled. It was some consolation to Cassandra that sections of the museum were to be made into indoor gardens, while other floors were being annexed into meat labs where lamb, poultry, and beef would be grown from test-tubes.

The more inevitable the closing of the museum became, the less potent her reasons for fighting to keep it open. Why re-traumatise people with humanity’s sins? she wondered. The world had moved on, the old crises of race, gender, and money were now entertaining parables for kids at school. The older people, who still had real-life experience of these issues, no longer held the reins of power, or their minds for that matter. Most of them suffered from Alzheimer’s due to the amount of mercury they’d inadvertently consumed in their food when they were younger.

Cass, we need your exhibition label. Is it done? Audre’s voice beamed into the office, snapping her out of reverie.

“Almost. I’ll send it to you by end-of-day. Send,” she said, and a beep from the speakers acknowledged her voice. She walked over to the bookshelf and pulled out a red, leather-bound book: the life report that she received from the department a decade ago. The pages were firmly cleaved to the book’s spine, unread, and when she opened the report to the summary section, she heard the spine flex and crack. There was only one paragraph she was interested in rereading.

The citizen has a proclivity for the past. Attracted to the documentation, and interpretation, of the meaning of past narratives for the present, it is advised the citizen pursues curatorial practices in line with the millennium goals of healing inter-generational scars. The citizen is encouraged, however, that by the end of the decade she should move beyond such proclivities towards the understanding that forgetting is its own cure. It is the Department of Happiness’s view that sins of the past are best buried and not spotlighted on walls, especially since crises of the past are innocuous in the post-climate era.

When she first read that paragraph a decade ago, she was grateful the department held very little political sway. But shit, do things change, she thought, sitting at her desk and pulling up a holographic word-processing document, floating above her desk. The cursor flicked on and off, patient, as if it had all the time in the world for her self-pity. She didn’t have the time. Audre needed her curator write-up, but she simply didn’t know how to capture what her work at the museum had meant to her, what this last exhibition might mean for the future.

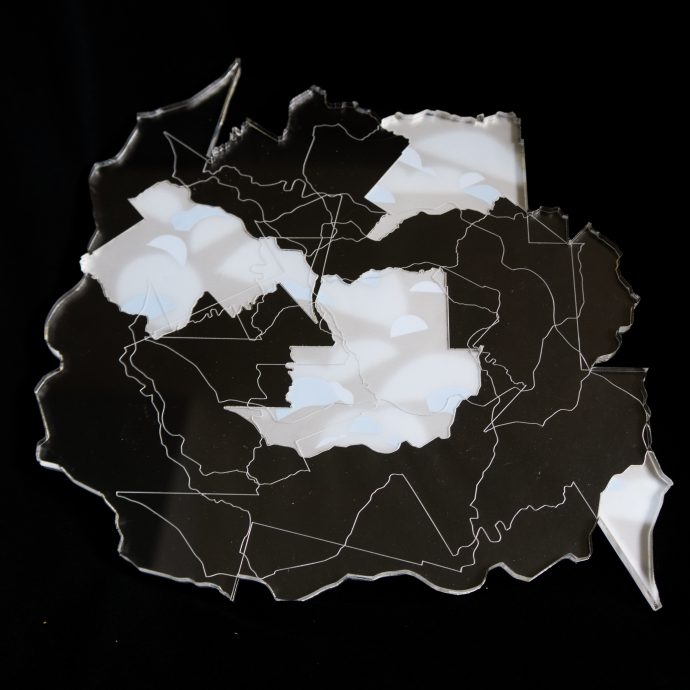

“Pull up zoom-in fractals,” she spoke into the computer and the screen morphed into a Koch snowflake: a fractal made from an equilateral triangle multiplied over and over by itself. The screen zoomed into the snowflake’s edges, revealing an endless perimeter of an identical, repeating, pattern contained inside a finite area. This is it, thought Cassandra, reaching for the small of her back.

Cassandra sat with Aanya on the couch. They passed the lips of a hookah pipe between them; smoke flavoured with watermelon and mint filled the apartment. Tony and Lebogang had gone to see Keano at the electroceutical surgery. He’d been booked in for an implant that promised to ease his frequent depressive episodes. All Keano’s doctors agreed that his was an especially resistant case. Each new psychiatric drug administered seemed to throw his brain chemistry into more tumult and this implant was the very last resort in a long line of past therapies. Both Cassandra and Aanya hoped it would work.

“So, you’re all ready for the final exhibit?” asked Aanya, pulling on the pipe and filling the lounge with the sound of its watery gurgle.

“Just about. But honestly, I can’t help but feel cheated. Like the work I’ve put in has been for nothing. And now with more people getting incentivised to receive this social cohesion implant I’m worried about the future of curatorship. I’m worried that things will become . . . flat.”

Aanya was quiet. She got up to change the head of the hookah pipe, pulling out a small bag of weed and sprinkling some into a fresh hookah head made of bubble gum shisha. “Cass, I didn’t tell you but . . . I got the social cohesion implant two weeks ago.”

Cassandra knew Aanya was building up to telling her something. It was part of the reason they’d stayed behind while the others visited Keano. She wasn’t angry with Aanya, she wasn’t even surprised. Below her bedrock of calm, however, there was a vein of disappointment that she tried to ignore. “Oh, that’s fine. This is the future, right? No more generational trauma passed down to children. No more history,” said Cassandra, mumbling the last phrase and reaching for the hookah.

Aanya nodded, unsure. Though she didn’t let on in front of the others, she liked Cassandra, so much so that often, while in Tony’s bed with Keano and Lebogang, she found herself wondering what reveries Cassandra was having in the next room.

The mixture of marijuana and tobacco settled into their bodies gently and lulled them. Mixed in with the instrumental piano in the background, both women fell asleep on the foldout couch. Later, when they woke, Tony’s door was closed and the hookah pipe had been cleaned and put in its place in the corner.

“They must have not wanted to wake us,” said Aanya, rubbing her eyes.

“Yeah, probably.” Cassandra noticed how close she’d gotten to Aanya during their sleep. She was close enough to smell the watermelon-scented smoke in her hair. “I should probably get to bed.”

“We can stay here,” said Aanya, a tender light in her eyes.

“I’ve got to be up early. Lots to do at the museum.”

“Sure,” said Aanya, reaching for the throw blanket and covering herself.

Moments later, Cassandra sat on the edge of the bed, door closed, wondering whether the vibes between her and Aanya were just in her head. It had been so long since she felt the urge to be touched by a specific someone. Ever since she had been in remission from the HIV, she decided to give herself time to find out what that meant for her, exactly. Living with the condition for a good part of two decades and then suddenly being declared free of it, even momentarily, made her want to take her next steps in love carefully. Her hopes of being free from the grips of the virus had been dashed years before, when another supposed cure was introduced to the public. She couldn’t bear to share the burden of dashed possibility with someone she cared for. Let alone a community. Hope was a burden that she decided was best carried alone.

The Affect Museum Presents:

A History of Happiness.

The sign above the entrance was big and bold, each letter receiving a different colour. People streamed into the exhibit space; invitations, advertisements, emails and social media messages had gone out to the many affiliates, companies, individuals, artists and institutions that had supported the museum over the years.

Cassandra stood in a corner, glancing over her exhibition write-up which had been uploaded onto the VR glasses that each person received upon entering. The glasses walked each person through the exhibit’s exquisite detail, providing hyperlinks to videos, podcasts, articles, and other images and commentary connected to the photographs on the walls.

Any history of happiness is a history of exclusion . . . Cassandra’s words flowed up on the VR glasses she had on. She walked over to the photo of Thích Quảng Đức on fire and clicked on a hyperlink, revealing an image of the monk’s scorched heart that had been preserved by his fellow monks as a holy relic, and later stolen by the South Vietnamese government who’d been in power at the time.

Cassandra felt the attention of those around her. From the murmurs and side glances she was receiving, she was unsure as to whether the exhibit was hitting the right notes. As head curator, she’d be judged harshly if the exhibition wasn’t received well.

Cassandra walked over to another image, trying to distract herself. The etymology of “hap” in “happiness” means “chance,” like in the word “happenstance.” And though any history of happiness is a history of those excluded from sharing in that happiness, there is always a chance that happiness can be stumbled upon in the unlikeliest of places . . . She stood in front of an image of a baby girl being thrown from a burning building by her mother. The photograph had been taken mid-flight, the baby girl floating above a group of strangers, all standing in the street with arms outstretched, desperate. Cassandra clicked on a hyperlink of video footage of that day. The baby had been thrown, and caught, so quickly that if the person taking the video hadn’t had their camera out at that very moment, the world would have missed it.

The murmuring in the room got louder. It became harder for Cassandra to concentrate. The commotion in the exhibit rose when a strange nausea overcame some of the people in the crowd. Suddenly, a man from the Department of Happiness ran across the exhibit floor and puked into a steel dustbin. Then, like the contagiousness of a yawn, more and more people started throwing up, some not even managing to make it to a dustbin.

Cassandra moved on to the next photograph.

But of course a desire for happiness felt by the wrong type of person, in the wrong circumstance, has often led to tragedy. Especially when that desire, that dream, upsets the happiness of others. A preconditioned happiness that has been engineered out of the spoils of spilt blood, fractured bone, closed mouths. Cassandra stood in front of the photograph of the hill at Marikana, afraid to click on any of the hyperlinks attached. Sometimes a photograph needs no further evidence, she thought. She took off the VR glasses, looking around. Security were escorting people out. Standing pools of vomit had been accidentally stepped in and were streaked across the white-tiled floor.

Audre rushed towards her, panting. “Cass, the exhibit is making people sick. We should shut it down.”

“Not yet,” said Cassandra, her eyes falling on the peacock-looking official from the department who stood, unmoved, in front of the last photograph in the exhibit. “Wait here.”

Cassandra walked over to the official, careful not to step in the flourishes of orange and brown vomit on the floor.

The official still had her VR glasses on and was seemingly immersed in the image in front of her. Cassandra wanted to see what she was seeing so she put on her glasses again.

Happiness seems to be situated outside of us. It is something we are after. Something we want inside of us. But something that cannot be held onto for very long. It doesn’t seem to be a permanent state and so to strive for it solely, above all else, seems too simplistic. This exhibit is about discordance, chaos, and, I would dare to venture, the betrayal of our invested hopes by people, institutions, and the cherished objects we surround ourselves with in order to feel comforted and secured. In order to feel that we are, indeed, on a road to somewhere.

The official took off the glasses and faced Cassandra. There were tears in her eyes. “The social cohesion electroceutical is important for the healing of intergenerational trauma. For the relieving of the emotional burden of history so that babies can be born stress-free, their nervous systems unfettered by the wounds their great-great-grandmothers carried in their flesh . . .” As the official spoke, her voice remained composed while her face contorted into a weeping knot.

Was this what implanting social cohesion into people’s brains did? Cassandra imagined the electroceutical inside the official’s skull working overtime to down-regulate the circuits that might cause her to remember the wounds of history, embedded in her body. Was this what the implant did to people?

The official, unsure of what was happening, wiped her tears and walked off. “I will see to it that no one is subjected to this garbage,” she shouted back, her tears falling into puddles of vomit.

Cassandra considered the photograph sitting in front of the official. It had been taken decades ago, during a global pandemic. The photograph was an overhead of the river Ganges. In it corpses had washed up onto the river bank like flotsam heaved from the guts of an ancient god. People were pulling bundles of flesh from the water, trying to put names to faces, while covering their own with masks.

Cassandra scrolled down the screen of her glasses to read the last paragraph of her write-up.

A fractal, though seemingly thrown into chaos, once magnified, always returns to an inexplicably ordered pattern. It is this that is so remarkable about life. That it can be lost so utterly and then regained. This exhibit, then, is about situating the weight of tragedy on the same scale as the weightlessness of bliss.

A month passed. It was the day of the museum’s closure. Cassandra sat at her kitchen counter, redacting parts of her life report.

The citizen has a proclivity for the past. Attracted to the documentation, and interpretation, of the meaning of past narratives for the present, it is advised the citizen pursues curatorial practices in line with the millennium goals of healing inter-generational scars. The citizen is encouraged, however, that by the end of the decade she should move beyond such proclivities towards the understanding that forgetting is its own cure. It is the Department of Happiness’s view that sins of the past are best buried and not spotlighted on walls, especially since crises of the past are innocuous in the post-climate era.

She closed the report as Tony and Keano walked out their bedroom, both sullen. “What’s the matter?” she asked.

“Aanya. She’s broken up with us. Says she needs to find herself. Whatever that means,” said Tony, sitting down next to her at the counter.

“I thought she was happy,” said Keano, rubbing his head. The scar where the electroceutical had been implanted was healed. He seemed better ever since, thought Cassandra, although it took him longer to get excited over things that he enjoyed doing. Even the news of Aanya’s departure seemed to reach Keano like a never-ending interlude between movements at an opera. Or maybe it wasn’t like that at all. Maybe Keano’s electroceutical fed the neural concerto of Aanya’s break-up into larger networks of perspective. She couldn’t decide which was better: fixation or detachment?

“She just needs space. Everyone needs to be alone for a time, right?” said Cassandra. The guys looked at her weirdly, almost accusatory. As she left the apartment and headed for the museum, she told herself Aanya’s leaving had nothing to do with her.

Later, as she entered the museum lobby, she came upon Audre standing in front of a small crowd. Some of the people she recognized from the exhibit opening. One by one, strangers started coming up and thanking her for reminding them what it was like to be overthrown by sadness and pangs of regret. Cassandra’s attention got pulled in all directions; she didn’t know how to feel.

“Cass, there is someone really important that wants to meet you,” said Audre, escorting her through the crowd towards an androgynous individual in a floral kaftan.

“Darling, is this the genius behind A History of Happiness? I’m Khumbula and let me just say, I am thrilled with the work you’re doing. It’s a fucking travesty that this museum is closing. But listen, there’s a couple of people I know who’d be keen to sponsor a nation-wide tour of your exhibit before it disappears. Let’s stir shit up, darling. Stir!”

Khumbula’s enthusiasm was infectious. Here was a slim chance to have her work shown to a broader audience and then, who knows, spark conversation, a movement against forgetting? Cassandra thanked Khumbula graciously and excused herself for the bathroom.

She locked herself inside one of the cubicles and keeled over, clutching the small of her back. An unfamiliar joy surged through her, straining to find an exit. Her breath became too slippery to catch. In her mind she saw Thích Quảng Đức on fire. How readily his body merged with the fuel he poured over himself, she thought. How instantly his ghosts charred and cindered. Humans do burn surprisingly well. But only because we haunt, and are haunted, so well.

Cassandra wiped her eyes. In the bathroom mirror, she prepared her face for the crowd.

Jarred Thompson is an educator and cultural studies researcher whose poetry, fiction and non-fiction have been published in various journals, notably the Johannesburg Review of Books, RaceBaitr, Lolwe, Doek! and FIYAH. He was the winner the 2020 Afritondo Short Story Award. You can find him on Twitter @JarredJThompson.