Thomas Alva Edison Memorial Park

I

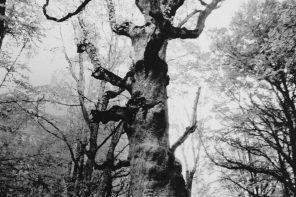

Pads and punks skim

a flat, reeded pond.

A crane flashes

from the crux

of kneeling

trees: a handkerchief

in an upper side

of suit, watchful.

The water is not at all

deep. The lightbulb

tower struggles to pull

above heaps of lost

leaves. Its base

wilts in filth

of swamp.

One eye, cloaked

with foam, between

highways, looking close:

the lake is seeded

by black plastic.

It was filled once

by hose. Looking

close: the flurry

of cranes is one

crane. It is one

exhaust-filled

lily. A light

poised in absolute

balance between

the heart

flaps of one

drab but

drifting

lilypad. Eggshell

plumed open.

Open mouth.

Some turtles drown

when it rains. Look up,

amazed, mouth open.

II

Someone is not

watching. Someone

around and decent

is not in the middle.

Someone is close

and specific

and fervent

about not coming

a step more towards.

There are four feet

up to the knees

in marsh.

Two sets

of lips touching,

pausing, pressure

closer. Someone outside

sees these bodies

and turns away, turns again.

III

Lilyroot filaments

a hundred thrown-

thread anchors

drift off the rafters

and are coated with electric,

gleaming algae.

There are streetlights

and there are stars.

Cranes, at night,

kick and bat

the light from the lake.

The park lies

blown and burst

each morning. The lovers

roll from the leaves, covered,

winged,

fingers tangled. Someone inflates

as they stumble toward sunup.

Masters Of Decimals

We are two beans

sprouting at the neck

when the world arrives.

It's the anemone's hour

of every stretch and we knock

heads by mistake: awake

with cheek full

of saliva, xylophone

of brine in stomach.

Having mastered decimals

watching Adult Math on television,

we bumped into sleep itself.

Had our detaching dreams

and you were living things

I wouldn't dream.

Has it been this way for long?

We tug and roll toward

each only other. Our bed envelope.

We have our terms,

we have our calculus,

and we have our calculus

in terms of shells. Not hardened

nor coated, but cloaked without in

the ocean's sine.

The moon rolls us into one

conch room. Mollusk long gone.

We curl around the helix.

One long lick

what we are.

I give you one long lick.

Our feelers emerge

from our collar

which is also our socks.

Still in bed, set in our places,

we are right (as the phone roars in our ears)

against each other, tenths, hundredths

The Sanitarium of Chunchon

I am sick so much, people call me hospital.

In the lightless mine, surrounded by jade,

I stretch my tongue until it uproots,

catch mineral sweat, taste fossils,

certain my circulation blushes.

Flaps of capillaries finally regular.

I rest from travel. I

am kicked in the head

by a woman with a liver

ballooned, diluted, fluid tomb.

Outside her body it

is seen dissolving.

Her husband plies her buttons

unpeels the blouse, and places jade

shards in orbits on the skin

of her belly and breasts. When she breathes

the pieces tremble

then remeet her,

edging between bones,

all pointing towards the center.

In my plane I cleave clouds:

A shoulder from the arm.

I hate that I have come here.

My blood at least

is moving. I gather stones for the man

and hand them to his hand. We dress her chest

with unstrung, evenly-spaced jewels.

A fit of coughs. She wakes the lid of her

own esophagus.

The man is her hanging cloud.

She is the acid soil of a temporary forest.

Sarah McCann was a Writing Fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has been published in such journals as The Bennington Review, Acrturus, Mortar Magazine, The South Dakota Review, and Hanging Loose. Her poetry has also appeared in Thom Tammaro’s anthology, Visiting Frost: Poems Inspired by the Life and Work of Robert Frost and an anthology from the Academy of American Poets, New Voices. Her translations from the Modern Greek into English have been recognized by the Fulbright Foundation, and a book of her translations of Maria Laina was recently published by World Poetry Books.