The Ruins of Nostalgia 1

In the fall we were nostalgic for the summer. In the winter we were nostalgic for the fall. In the summer we were nostalgic for the spring. But in the spring we were not nostalgic for the winter, not even for its quiet, or its hot cocoas, or its video fires, though we did ask our father from time to time to tell us about how, when he was a child, the man-made lake in the middle of our city froze over every winter, and how one December day he broke through the ice and was only saved from drowning by a neighbor boy whose name he can no longer remember. We were nostalgic for the frozen lake we had never seen, that is, for the lake we had never seen frozen, the man-made lake we had swum in during the summers after the lake froze. It was hard to imagine the summer lake frozen. It was hard to imagine the winter lake summery. It was hard to imagine the lake being made, and not just spontaneously welling up its murky green effluence. We were nostalgic for winters that had descended before we were sentient, as if those winters existed in snow globes we could stow on our nightstands and dream of falling and falling through the ice we are always rescued from by neighbors who become strangers over time. The lake is always melting in the ruins of nostalgia.

The Ruins of Nostalgia 2

We were clicking through photos of a lost Mongolian tribe on the internet on our laptop after work. We had clicked on the click-bait headline “lost Mongolian tribe” and were looking at a photo of a girl clutching a baby reindeer like a stuffed animal, bathing it in a lake. We were considering the symbiotic relationship of the lost Mongolian tribe to reindeer, while looking at a photograph of a human baby asleep propped on a furry flank. We were thinking about anthropology, and about the paradox of the observed observer, and wondering how a Mongolian tribe can be lost if it has already been found by the observed observer, who has lost her own glass eye of objectivity when she has found what it is she wanted all along to see. We were imagining anthropologists observing our own behavior, noting down our symbiotic relationship to our laptop, noting down the number of clicks we expend on click-bait hoping to satisfy our nostalgia for symbiotic relationships with animals we’ve never had, noting down our nostalgia for the possibility of living lost, not found. Cities had for a century and a half permitted some of us to live lost, but forces beyond our control were now insisting that we live found. * Under the final photograph it was written that the lost Mongolian tribe survives on money from tourists, on observed observers who come to take rides into the past on symbiotic reindeer. So, like videos marked “rare” that are uploaded to the entire internet, the lost Mongolian tribe was never “lost” at all. And that’s the thing: the observer is always the observed, and the observed the observer, in the ruins of nostalgia.

The Ruins of Nostalgia 3

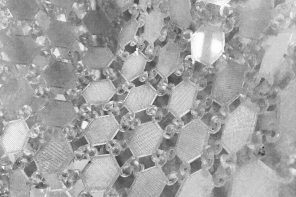

She saw a dactyliotheca in the museum, a wooden cabinet holding three “books” containing not pages, but dozens of tiny drawers filled with white plaster cameos and intaglios—profiles of queens and goddesses sunk into ovals (intaglio—negative), or raised out of ovals (cameo—positive), rows and rows of cameo or intaglio profiles, raised or sunk, positive or negative, and she thought of the cheap black-and-white cameo pendants she and her sister had been given in Italy, the pearly profile supposedly “mother of pearl,” a new term she hadn’t understood—how did pearls have mothers?—but looking suspiciously like plastic, and thought of the cameo role the cameo had played in her life, like her sister’s friend Cameo, the three of them little girls in the sunken porcelain bathtub, Cameo with brown braids almost black, the cameo role Cameo had played, playing herself, in profile, in the bathtub, and thought she could make her own dactyliotheca with dozens of drawers full of rows and rows of cameos and intaglios, people who’d appeared and played themselves and disappeared—some positive, some negative—and like the Italian cameo in a drawer somewhere forgotten or rediscovered from time to time and considered—plastic or mother-of-pearl? Positive or negative? * What about people who’d played both positive and negative roles as themselves? Which was pretty much all of them? * Truth is the mother of beauty, necessity is the mother of invention, plastic is the mother-of-pearl cameos her mother, then young, now old, had given to her and her sister in Italy, in black and white, like the checkerboard marble floors of the palazzos they saw in postcards but never entered, leading to the positive or negative ruins of her nostalgia.

Donna Stonecipher’s fifth book of poetry, Transaction Histories, is forthcoming from University of Iowa Press in Fall 2018. Her prose book Prose Poetry and the City was recently published by Parlor Press. She lives in Berlin.