The first time I watched The Sixth Sense, I blinded myself. I was nine years old and an anxiety-prone child with an acute faith in and fear of all things paranormal. Upon the film’s completion, I wrapped my head in a knit periwinkle blanket that smelled—like most relics of my childhood do—of dried cat urine and stale cigarettes. This odor was worth suffering through for the protection provided. In fear, I’d fallen back onto the comforts of certain infantile misconceptions. That is, life is easier through the cracks. What we cannot see cannot hurt us. I spent the remainder of the day stumbling from room-to-room, feeling my way around the house with my feet. My hands were occupied holding my makeshift blindfold in place, that blessed threadbare garment protecting me from wayward spirits.

It would be 2013 before I revisited the film. I was 23 years-old, a hardened horror fan and a thorough skeptic. By this point, my belief in the paranormal (responsible, I think for the staying power of my discomfort with The Sixth Sense), had vanished. There was no God. There was no afterlife. Any fear I felt during a horror movie lasted only for the film’s duration. I re-entered The Sixth Sense unafraid only to find that fear was not so much the film’s goal. The biggest twist in The Sixth Sense is not—spoiler alert!—Bruce Willis has been dead the whole time. It is that the film is not a horror movie at all.

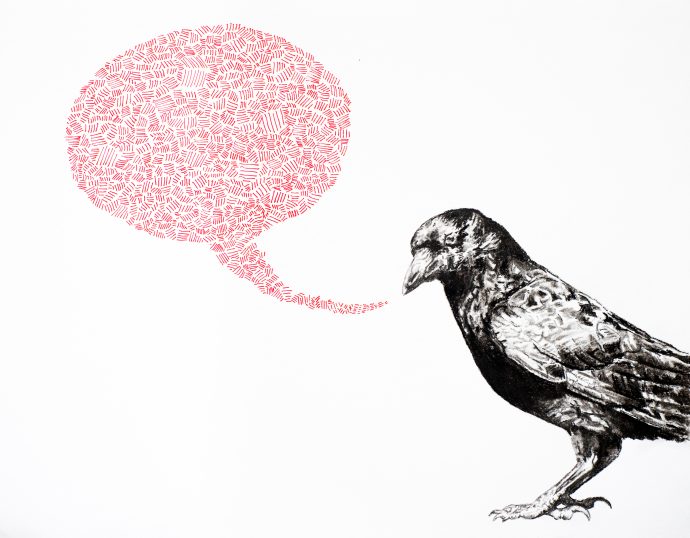

Horror is a genre that exploits existing fears of death, seeks to terrorize by loping around the unknown long enough that—if the story and visual effects are successfully executed—the audience squirms in profound discomfort. The Sixth Sense’s central message, conversely, is one that discourages living with an overabundance of fear. It’s the story of Cole Sear slowly opening up to Dr. Malcolm Crowe. If one pays attention to surnames here, Malcolm’s nature seems almost obvious. Sear points, of course, to the fact Cole is a seer, a psychic, a medium, one who perceives what others miss, and crows have been—in much of European mythology—portrayed as harbingers of death. Cole is initially frightened of Malcolm. Given his gift, we can assume that he sees Malcolm bearing the gunshot wound that killed him. Malcolm’s benevolent nature, however, wins Cole over. He opens up, he talks, he comes to share his secret. What does the seer learns in conversation with the crow? That the best means to cope with tortured spirits is to talk, to listen, and to understand. A horror film reinforces existing fears. The Sixth Sense seeks to deconstruct the nature of existing fear to highlight its shortsighted nature. That is, the film shows us what we need not fear: the very sick, the mentally unstable, sufferers of abuse and neglect, one another, hauntings themselves. The hauntings here, really, are no more than a metaphor.

Weeks after my grandfather’s death, my younger brother swore he saw our grandpa seated in the lounge chair in my grandmother’s living room: a transparent vision that vanished within moments. Seeking a logical explanation to this apparition, we discovered an online study which theorized that ghosts could be explained through dust. The study proposed that people leave imprints of themselves on the spaces they occupied in life. When they pass, the dust remains parted in the air, as if it were waiting for their return, and creates what appears to be an outline of a person.

I do not believe in God but I do believe in metaphor.

The Sixth Sense resonates with such metaphors, objects and spaces which harbor echoes of their histories. The film is aptly set in Philadelphia, a city which retains deep imprints of its past. The film emphasizes, however, that there is a disparity between these imprints and the stories people tell about them, the origin myths of American exceptionalism. This disparity is illustrated in a scene wherein Cole’s teacher asks what the schoolhouse was used for 100 years ago. “They used to hang people here,” Cole responds. “They pulled the people in crying and kissing their families bye . . . People watching would spit at them.”

Cole’s teacher immediately shuts down this story, choosing to instead emphasize the school’s former status as a legal courthouse filled with respectable lawyers, politicians, and lawmakers. Whoever told Cole about the hangings, she says, was just trying to scare him. Both stories are equally true but only one story is presented as factual by the powers that be, the more gruesome tales witnessed only in a bare, spectral form.

What I find remarkable about my grandfather is that, despite his alcoholism, he achieved the increasingly tenuous American Dream. His was the tale of a man who grew up on a potato farm, put himself through through seven years of school, and started a law firm on a wing and a prayer. It was a mythology, the triumphant epic of one man pulling himself up by his proverbial bootstraps to surpass the confines of childhood poverty. In reality, my grandfather’s success was a combination of dumb luck and—given he was born a white, heterosexual male—a great deal of preexisting privilege. His life was not a manifestation of American possibility. It was an anomaly. I think my grandfather might have known this, given his lack of romantic notions about America. He was consistently disappointed with the unacceptable gap between what should be and what is, the crushing dissonance between reality and the ideal.

In her Mythology, Edith Hamilton writes of Dionysus, god of wine, and how imbibing booze made Greek men feel like they held more within themselves than they knew, that they themselves could become divine. Anyone who has ever been drunk recognizes the sensation of becoming awash in a sudden self-aggrandizing glow, overcome with a hunger to chase that feeling and forget all insecurity. There is indeed something Godlike about drunkenness, something strange and mythical about intoxication that makes you feel bigger than yourself. Perhaps that’s why my grandfather drank. When drunk, he could reach a place where he felt deserving of the pedestal on which he was placed.

His drinking was an ugly part of his history, one that was never quite public knowledge. But in its bare and spectral form it poisoned the family tree.

Before Haley Joel Osment auditioned for the role of Cole, his father read the screenplay twice. He informed his son the film was not a horror movie. It was a story about communication.

The turning point of The Sixth Sense comes when Cole speaks to the ghost of a child named Kyra. She appears in his red tent, shaking and vomiting, and Cole flees at first in fear. Then, after a moment’s recollection, he returns. He pulls the blanket off Kyra and asks, “Do you want to tell me something?”

Cole learns that Kyra’s mother, likely suffering from Munchausen syndrome by proxy, was slowly poisoning her. When Cole attends Krya’s funeral, guests whisper how her sister is growing ill as well. Cole reveals the truth about Krya’s death to her father who, devastated, confronts his wife and in doing so saves his other daughter from the same fate. It is a moment that is tragic, but also a relief, a victory even. Kyra is gone, which is devastating, but at least the deadly cycle has ended. There will be no more bodies dead from this disease.

Alcoholism is a force of obfuscation. Fights, confrontations, proclamations of love and fear, expressions of raw and honest emotions in all their varied forms more often than not occur in a brain-space that does not really exist. By morning, emotions dissolve into the realm of intoxication, a space where fact blends into memory’s fabrication. The deadly cycle is never quite broken as it’s never quite addressed, at least not with any great success.

I have held within me, my whole life, a desire to confront fear through communication, to combat the unknown by pulling it into the realm of the living. Such a thing is, in my family, simply not an option.

We once had an intervention for a family member. During a preliminary meeting, the interventionist—a former pill addict with over 15 years of experience running interventions—pronounced, a note of shock in his voice, “This family . . . needs work.”

The tragedy of alcoholism is not just that it brings out the ugliest, rawest, most unlovable aspects of the addict. An equal tragedy is how those around the addict lose their capacity for empathy, how loving an addict teaches you that feelings of genuine kindness, concern, and love do, actually, have a finite value and, yes, it is possible to reach the limits of that value. It is possible, when baking banana bread alone in your studio apartment in Chicago at 10 o’clock at night. It is possible, when in the midst of mashing the soft yellow of the bananas into the brighter yellow of the butter and the egg yolks. It is possible that, in this moment, a phone call will come from your cousin, a phone call detailing some unsettling news about a relative—here’s the latest, she’ll say, taking on an inappropriate tone of nonchalance, the tone of one who has made far too many phone calls of this nature in her 22 years—and it is possible then to realize your compassion is gone.

When it came, this revelation was much like losing faith in God. It came suddenly and yet must have been building somewhere on the periphery for a while. The feeling that followed was, for the briefest moment, also akin to losing faith, that sense of liberation at no longer having to force it. Following the momentary elation, however, came a crushing guilt.

I am not a believer but, for a while, I would pray some nights. I started out praying for that particular family member but then prayed for myself. I asked God to make me a kinder and more patient person. I asked Him to help me reject feelings of hatred, disgust, and anger, feelings that had long ago lost the cathartically self-righteous gleam that made them feel acceptable, even fun, to indulge and were now just plain, naked ugly. Such emotions could derail me. I could spend whole days going over past wrongs, seething in a silent rage that robbed me of the ability to function. All I could do was pray. I had no hope these prayers would be answered or even heard. I was no more a believer then than I was that Tuesday afternoon at 16. It was just that I hoped the declaration alone—asking to be more than I possibly could, owning up to my inadequacy—would somehow reverse the problem. That’s the first step, isn’t it? Admitting you’re powerless, that your life is unmanageable due to addiction.

In Alcoholic’s Anonymous, Step 8 is to make amends. One is supposed to apologize to anyone they wronged when drinking.

After the intervention, for months, I waited for my apology. I’m not sure what I was expecting. Did I want this family member to apologize for never seeing me on my birthday because it fell after Christmas and therefore he would still be sore about whatever drunken disagreement he had with my father that year? Did I want him to apologize for sending me an angry, incoherent e-mail in the middle of midterms my senior year of college, while I was both finishing off my degree and applying for graduate school? Did I want him to apologize for the late March afternoon when he left me six angry voice mails regarding a photo I posted of him on Facebook? Did I want him to apologize for, later that same afternoon, posting a status on his own Facebook page saying I was a disgusting pig? There were other wrongs, worse wrongs, that I felt warranted an apology but they involved my father, my siblings, my grandmother. The interventionist had told us when we were writing our letters it was very, very important we only focus on the wrongs done to us, that indulging feelings of indirect outrage and offense was time wasted as we could not adequately express or even imagine the pain of others.

I fantasized about an apology, but the imagined scenario never got further then a phone call and the words, “I’m calling to apologize for…” I’m not sure I wanted an apology for any one, specific thing. I just wanted my pain acknowledged. I wanted to know he understood that he hurt me, and that my self-esteem and self-image were bruised because of it. The apology never came.

I talked to a friend who is married to a recovering alcoholic. I mentioned this family member and how I never got the apology promised by Step 8. “He may not have gotten to that step,” she said, “Or he may not think he needs to do that step with you. Which is sad. But it’s not your fault.”

“I don’t think he believes in God,” I said, “I wonder if that’s why he stopped going to AA. Maybe he felt alienated.”

“It doesn’t have to be God-God,” she said, “It’s a ‘god of your understanding.’ Which is easier for me. Mine is nice and manifests itself as a tiny pink wing-ed elephant. Wing-ed, not winged.”

I was struck by this because, I shit you not, when I was born the family member in question brought me a plush pink elephant in the hospital. I know it sounds absurd, the future alcoholic, at 15, bringing a newborn a pink elephant in a rare gesture of familial kindness, but it’s true. I still have the elephant, and it is still that same shade of grapefruit gut pink.

After talking to my friend, I prayed more, prayed while thinking of the wing-ed-not-winged pink elephant, but nothing changed. No matter how many nights I prayed for the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference, I still felt angry, confused, and wronged. I felt no restoration of empathy lost.

Joan Didion says in her Blue Nights, speaking of her daughter’s adoption, that there comes a point where a family is, for better or for worse, finished. She’s speaking to the fact that some relationships cease evolving and exist, instead, in a homeostatic state of dysfunction or discontent. We have to, with time, accept that our mistakes and the mistakes of others will not be fully rectified or even acknowledged. I will never get my apology. Step 8 is a privilege that will always be withheld.

Blue Nights is a memoir true to life in that it’s utterly unsettled. Herein, Didion recounts the death of her only daughter, Quintana. There are no silver linings in Didion’s world, no proclamations of the restorative powers of memory to ward off unbearable grief. On bad days, on those mornings I wake up to find the world has a funny angle to it that makes everything look stupid, I hunger for catharsis. I can love and respect a work that, like Blue Nights, refuses to tie up loose ends but need the occasional gratification of a work that does. The ending of The Sixth Sense is why I came to love the film, why I come back to it during spells of unfurled dissatisfaction.

I need to believe in a world where fear can be defeated.

The Sixth Sense is perfect storytelling. It eschews the mysterious, sequel-prepping endings typical of many blockbuster hits marketed as horror or suspense. Instead, it offers a Chekhovian finale that leaves no guns unfired and grants the characters as happy an ending as can be expected. Cole’s relationship with his mother improves as he opens up, sharing his gift with her by delivering a message from his late grandmother. Malcolm realizes he has died and, after bidding his wife a tearful goodbye, at last passes on to the other side.

I quiver thinking of this ending, feel the fluttering of elation that often accompanies experiencing a particularly well done bit of art. I have an uninhibited affection for the film.

Didion famously wrote that we tell ourselves stories in order to live. “We live,” she wrote, “entirely . . . by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

We tell ourselves stories in order to live because stories provide comfort when life fails to do the same, when our experience becomes unacceptable to us. We mold it, unfairly, into a story, into hasty justifications coupled with some romanticizing of the past, false nostalgia and a dash of imagination to boil our most difficult moments into digestible terms. Sometimes the narrative is broken and there is no frame in which to neatly fit our experience.

There are some hauntings that remain un-exorcised and some ghosts that will never, never talk back.

Erin Wisti grew up in Houghton, a small and unusual town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula where John Oliver once did stand up and was suitably baffled. He still talks about Houghton in his routine from time to time. Erin left Michigan immediately upon finishing college, moving to Chicago where she got her MFA in nonfiction from Columbia College. Her writing has appeared in The Butter, Role Reboot, Fanzine, Bayou Magazine, Ampersand Review, and other places. Erin started writing around the age of 3, where her father told her that her previous career goal of becoming a potbelly pig was impossible. She currently lives in Los Angeles and serves as senior editor at Entropy Magazine.