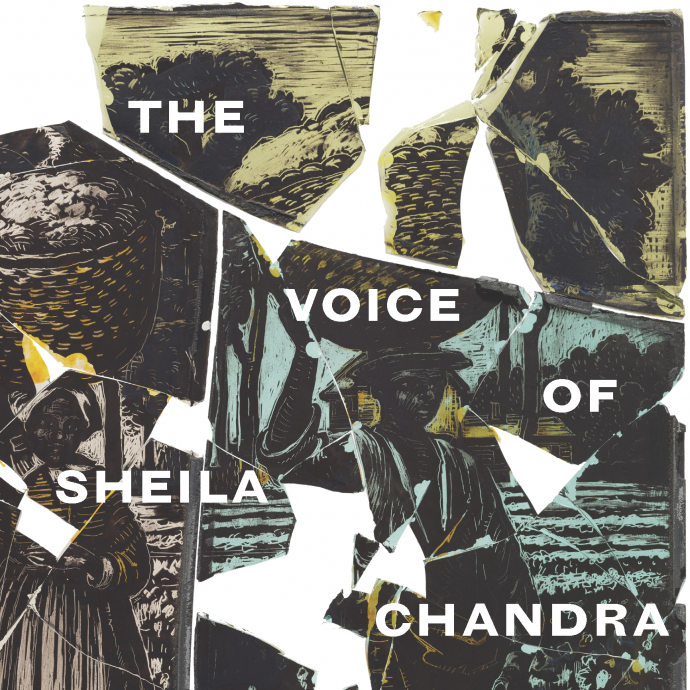

The Voice of Sheila Chandra by Kazim Ali. Farmington, Maine: Alice James Books, 2020. 59 pages. $17.95, paper.

Earlier tonight, I sat on my apartment balcony in the cold and stared at the few stars that rampant light pollution allowed to break through. I listened to the sounds of what I’d usually call a quiet night—rainwater dripping from oak leaves, an engine revving on the other side of Providence, the drone of electronic music from my neighbor’s apartment across the way and someone singing downstairs, a child maybe. I sat and listened; I stared at the mostly black sky and thought of the idea of God. I don’t often sit outside in the cold listening to winter sounds and thinking of God, but having just finished reading Kazim Ali’s newest poetry collection, The Voice of Sheila Chandra, it felt like the only appropriate thing to do.

“So how do you discern a shape for / what is often called god” Ali’s speaker asks.

I don’t know. The sky is mostly black save for Mars to the southeast and the sparse smattering of stars to the north, to the west. The sky for me is the shape that fills the space between horizons and god is not the sky but god might be a shape and that shape might be a filling-in of some between.

“God’s like you a misfit / You don’t fit he don’t fit” Ali writes.

Yes, that seems more realistic. The filling-in is an illusion and the sky isn’t the shape between the horizons even if it seems that way. God isn’t a shape; what is often called God is a shape.

“Do you know what your body is do you know what god is” Ali’s speaker asks.

No, I don’t. No, I don’t. I’m in a body and I’m thinking of god and I feel certain of each of these things but each of these things still feels tentative. I feel my body like an illusion, a filling-in of some between. I feel the idea of god but it is just an idea and the sky above me is mostly black and there are horizons to the north, to the west.

“Do you know what god is what’s not do you know what art is what’s not do you know what a nation is a citizen a crime”

No.

“What if God is improvising like Coltrane”

It’s both God and god, it’s the possibility that each is music, it’s the what if, the maybe, the sounds filling the night below the mostly black sky, electronic music droning from my neighbor’s apartment, the water dripping from oak leaves. Is this an improvisation? Is it the music that matters?

In The Voice of Sheila Chandra, it is very much the music that matters. I’ll call it a mosaic—in this book of three long poems punctuated by four short poems, a mosaic of fragments, testimonials and scattered shards of living, comes together in music, through music, in celebration of music and in service of music. The subject is music. The method is music. The ethos is music. The obsession is music. Ali’s writing, which includes numerous poetry collections, novels, works of translation, and books of essays, has been often praised for its lyricism and musicality. This new collection is an exciting addition to an already-expansive body of work.

The book fittingly begins with a command in the direction of music: “Small animal recite.” This opening poem, “Recite,” sets the stage for a book saturated in recitation and the cadences of spoken language. If you’re the kind of reader who likes to and is able to read poems aloud, you’re likely here to follow this poem’s prompting. You’re likely to spend the rest of the reading curled up on a couch or on a lawn chair on a second-floor apartment balcony vocalizing the poems, chanting through the marvelously tangled syntax and rich textures of Ali’s assonance and consonance and wordplay.

If The Voice of Sheila Chandra is rich in sound and music, it is comparably rich in its engagement with transnational identity and culture, both historical and contemporary. I previously described the book itself as mosaic, and the first long poem, “Hesperine for David Berger,” is an elliptical mosaic of stunning scope.

In a series of short prose stanzas, Ali draws from both research and lyric interior to weave together a wide variety of scenes. The poem follows Corey Menafee, a Black employee at Yale who in 2016 smashed a stained-glass window depicting enslaved people picking cotton: “Begin with the dining room attendant at the ivy-covered university who smashed the stained-glass window because we are now actually going to change history.” It follows David Berger, the Israeli and American athlete who was taken hostage and killed during the Munich massacre at the 1972 Olympics: “And so I shout down with ragged throat this encroaching blue that brings dawn then brightening day then David and his teammates hustled by the kidnappers into a helicopter bound for the airport promised passage out of Germany.” It follows Imran Qureshi, the Pakistani painter who “does not paint on canvasses but paints little blossoms on the ground on the wall in corners of the room they bloom like water or blood or light.” It follows the Qawwali singer Amjad Sabri as he “groans his throat open in ecstatic sound aiming to reach from the muck of the earth all the way into heaven” before he was assassinated in Pakistan in 2016. It follows Mohammed Al-Khatib, Olympic hopeful training “as a sprinter with neither spikes nor coach nor starting block.”

The poem is expansive and entrancing. As it interweaves each of these subjects, questions emerge about the nature of violence, about human passion and compassion. The speaker questions and declares, tangles flickering images of individual lives with cosmic conceptions of time and divinity, verses from the Quran, the speaker in travel and discovery. Ultimately, the poem is a matrix of lives. Its form is also its idea: “Bodies separated by years and miles and religion and law may release their own energy may transfer into one another may be the same body.”

While music plays an important role in “Hesperine for David Berger,” it is even more prominent in the title poem, “The Voice of Sheila Chandra.” This sequence of forty loose sonnets continues to blend research with lyric and the music of language. Whether you stop to do your own research on singer Sheila Chandra or jump straight into the poem, you will feel her music’s influence on Ali’s poetics.

Known in part for her series of albums and live performances with a solo, drone style of vocalization, Chandra spent much of her career fusing British and Indian musical aesthetics. When she began focusing on drone-style singing in the 1990s, her music began to emphasize the voice itself as instrument—her hypnotic vocalizations are rich and powerful. Ali’s opening sonnet invokes Chandra’s droning vocalizations as it fronts a long rounded vowel assonance:

Ration of the drum a hum a

Home womb and um

She OM moaned in the loam

Dark earth come Sheila

Dame ocean dome this poem

Roam to tome tomb foam.

Again, style and form mimic subject and idea, and throughout “The Voice of Sheila Chandra,” the music of the language constantly interplays with the subject matter. The poem tracks the implications of silence and energy that is not vocalized, in life or in a song or in a poem, as it chronicles Chandra’s loss of voice in 2009 when she began to develop symptoms of burning mouth syndrome, a rare condition that leaves those who experience it in intense pain whenever they vocalize. It weaves the speaker’s own experience of body, of sexuality and joy, of despair and mourning, into the explorations of music. The result is an ambitious and expansive long poem that celebrates sex and recoils at torture, muses on nationality and interrogates colonial ideologies, dissects masculinity and listens to the rain falling.

Ultimately, the poems I’ve described here are only part of the rich tapestry this book has to offer. In the end, Ali’s speaker yearns against isolation in “Wrong Star”: “Wrong star I chose / To sail under alone / I did not want / To be alone.” The poems, too, do not want to be alone. They hold hands with each other and listen to each other’s songs. And they insist that song is ongoing, that “there is no beginning to any song only the place / the singer picks up the tune.”

Jacob Griffin Hall was raised outside of Atlanta, Ga and lives in Columbia, Mo, where he is a PhD candidate and works as poetry editor for The Missouri Review. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in New South, DIAGRAM, New Orleans Review, New Ohio Review Online, Salt Hill, and elsewhere.