In our rush to amend or forget the disasters of the 20th century, its liminal realms were purged and many doors to possible futures were locked and abandoned. Not just the consumption of art, but also its production was rationalized under capitalist models and for-profit education systems. At the end of the 1970s, a long era of openness to mysticism and spiritual inquiry (connecting the Romantics to the Surrealists to even Modernists like Buckminster Fuller) ended with its bitter commodification under the New Age banner. Then, briefly, a new digital frontier appeared. The Internet, which seemed like a realm of infinite possibility in the 1990s, has since been shaped by a small handful of technocrats, staunchly aligning itself (in terms of dollars and bandwidth) with the mundane. The artist today exists in an ecosystem that is friendly to list makers and traditional storytellers, but hostile to any inquiry or movement that does not prioritize the real or honor the preexisting. The holiday box office champion received widespread acclaim for its studied, scene-for-scene imitation of its forebear. It’s a “golden age” for television largely because producers now do a much better job of conforming to audience expectations. In this environment, where there is scarcely room for the possible (let alone the impossible), the abandoned doors of the last century deserve another look.

Behind one such door is Roger Gilbert-Lecomte (1907-1943), a French poet and co-founder of Le Grand Jeu (The Great Game), a group and journal that published three issues between 1928 and 1930. Invited to join the Surrealists, they declined—perhaps because, in consideration of some of their more extreme ideas, Surrealism seemed like a retreat. For Gilbert-Lecomte, the magazine was a weapon for spiritual, social, and political change.

In the essays and fragments collected (for the first time in English) in The Book is a Ghost: Thoughts & Paroxysms for Going Beyond, Gilbert-Lecomte positions himself outside the rational and spiritual camps that divided artists of the era, somewhere beyond dualism. He aims for what translator Michael Tweed calls “a godless kenosis.” Describing the goal common to all of his work, Gilbert-Lecomte says: “I will try to illuminate, with every light possible, this untranslatable revelation that I bear deep within my inner darkness. No doubt I will die before I make myself understood, but that lucid despair does not resign me to pessimism. Patiently, I will speak with everyone on every level.” In part, this revelation included the notion that “one can experimentally escape the duration of the flow of the will-to-live until becoming eternal.”

Aspiring to “a metaphysics of absence,” the body was not explicitly an obstacle for Gilbert-Lecomte as it might be in ascetic religious practice, though addiction did become a problem for him. Beginning as a teenager with his friend René Daumal, he experimented with automatic writing, yogic practices, and drugs. According to Tweed, “any so-called extra-sensory experiences which might arise were not artistic fodder but signs, heralds of the possibilities that lie beyond the common acceptance of the limits imposed by life and society.”

Gilbert-Lecomte is somewhat indifferent to the actual results of the artistic process. Art does not exist for society or for its own sake but as a means toward an ultimate transformation. Once a novel has been written and read by its author, it might as well be burned, because it persists eternally, in his view, in the cosmic record. The entire field of human endeavor remains accessible via some subconscious mechanism similar to instinct, “that ghostly cloud in the shape of a dog that connects all dogs and through which all dogs communicate.” In another essay, he defines poetry as “a specific state of consciousness engendered by an emotional shock” and the transmission and study of this state. Here, too, the poem-as-object is subservient to the effect of the shock that produces it. It’s a bonus if the poem, like a zen koan, produces a similar shock in the reader.

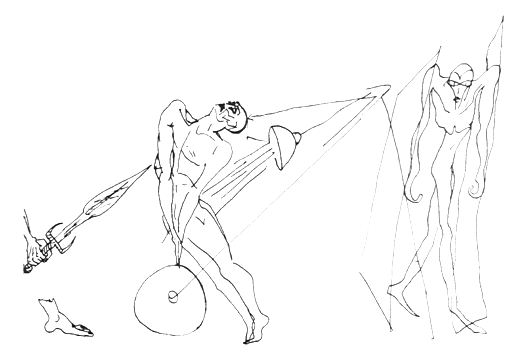

Despite his deep pessimism about the state of cinema (an after-dinner opiate subject to the “absolute dictatorship of capital”), he predicted that, as a “mediator between mind and nature,” it would eventually become “a mode of knowledge, an actual form of the mind.” In this future cinema, the filmmaker’s task would be “to adapt one’s entire mental life to the screen,” including both forms that can be illustrated with sound and image (such as dreams) and forms that cannot, with the goal of granting access via the screen to new states of consciousness. The drawings reprinted here might give the reader a better idea of what he is after. It’s impossible to guess what Gilbert-Lecomte would think of the films made in the decades since his death (Brakhage or Denis or Lynch), but it’s not hard to imagine a similar essay on today’s video games and virtual worlds, which have perhaps even greater potential as a form of mind, but are no less subservient to capital.

Gilbert-Lecomte published two collections of poetry in 1933 and 1938, but gradually succumbed to morphine addiction. His girlfriend, whom he had intended to marry, was sent to Auschwitz in 1942. He died of tetanus the following year, leaving a slim briefcase full of essays, letters, drawings, and notes. Without the explicit sanction of Breton’s Surrealists, Gilbert-Lecomte was on his own journey from the beginning—more direct and in some ways more ambitious than his contemporaries. The Book is a Ghost is both a record of abandoned possibilities and a set of incomplete formulas from which to set out once again.

Christopher Kelly is a staff reporter for the Tokyo-Chunichi Shimbun. He lives in Washington, D.C.