Mothers

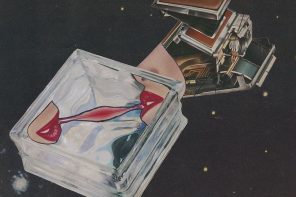

Today I allow myself to be a passenger on the plane with my mother and her mother. We’re flying it’s 1974, my mother is twelve and my Lola is thirty-one and I am eighteen years from being born, and the Philippines is under martial law so we’re getting the fuck outta there. Over the Pacific, the three of us sit, nervous and unsure of what’s to come. On the plane we think about our goodbyes. We wonder if we’ll miss our home in the tropics. On the plane we speed towards an infinite number of different futures, like branches, like constellations of possibility. Astral projections. In each image we are smiling, happy, American. On the plane we don’t consider what we’re leaving behind. We don’t think of when we might return, of what will happen to our old home when we’re gone. On the plane we sever a tie. We let ourselves, flying from a past home towards a future home, become the kind of women who can adapt. The kind of women who adopt new homes. So barreling forward, we become women who, in leaving, may never return home. Women who may never really be home. Perhaps we don’t just build homes, we build ourselves into homes, becoming the kind of women for whom home is just that — barreling forward.

Weather Patterns

after Marisa de los Santos I Summer in Louisiana, I let the back door swing open, and every day the rain poured down. Rain caught the wide leaves of our tree, lush against the chainlink fence. That sky hung heavy, beautiful, gray in those storms. There was a gang of chickens almost ever-present, howling half the day and kicking up leaves. Only in rain were they silent. Only hidden under our house, or the neighbors’ houses with the cats, in a world parallel to ours, underneath us, outside. There was something about that sky — like a leaky ceiling, waiting to open. Before a storm, New Orleans would go silent. If it really rained, some parts of town would flood, the bayous would spill into the street, until the streets became bayous. II Like those bayous, there are creeks or tiny rivers trickling through Manila. It’s 1970, my mom is running, no shoes, in the creek behind Juana’s house. Now she has callouses as big as coins on her feet. Back then, one of her aunties had a farmacia, she said, like a lean- to, with corrugated metal outside — the rolling gate propped open with a stick. In the tropics my mom, as a young girl, would sell shaved ice with her cousins. A whole family I’ve never met — and what about that heat? The air, sticky. Wide, flat banana leaves, catching rain. III Remember that one hurricane, we stocked the house with bottled water and a zillion kinds of snacks, in case of a flood. We stayed inside and probably got drunk all day. Skin dry, dehydrated for the first time. We played board games and watched movies on the mattress on our living room floor. It was supposed to have been a big one. The sky, heavy and low like always. It spat all day but never really rained. We opened the door. IV It’s Christmas and there’s a storm in the Visayas some thousands of miles away. My aunt Candice checks her phone every hour. There’s wreckage on the news in the morning. Tin roofing flying through the air like candy wrappers, weightless. The wind swirls rainwater like a twisted alchemy. Like clothes and clothes and clothes strung up on the line can hold through the storm somehow stronger than trees.

Soleil Garneau is a Los Angeles-based writer. She is an MFA candidate in UC Riverside’s Department of Creative Writing.