This Body

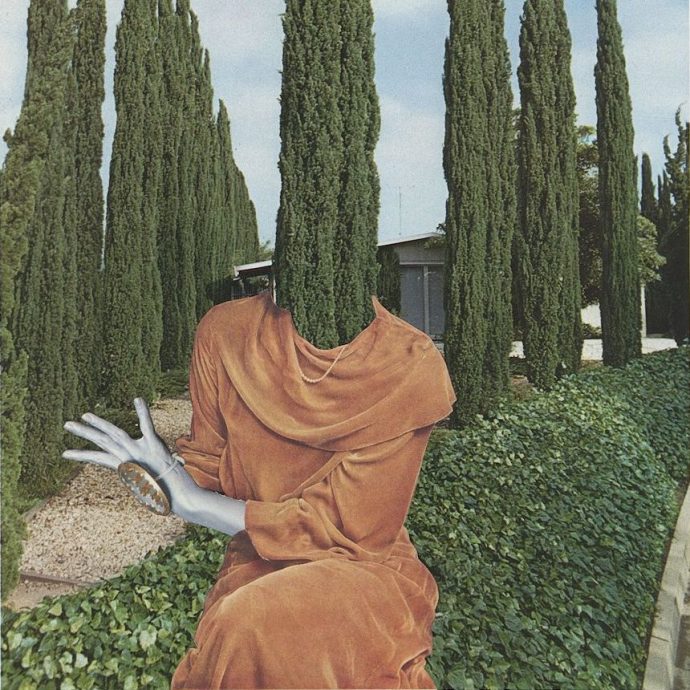

When I was younger, and when I was most injured, most in pain, doctors told me to picture my back as an invasive plant. To imagine the spurred bones of my spine covered in Lamb’s Ear, Medusa, Fiddlehead Ferns. I saw my injuries as prowlers then. The blood, the tactile-ness turned into leaves that cut across the end of me. At night I saw light, just as the doctors had told me to. Orbs circling through the garden in my broken sacrum. I tried to make this light grow across pelvic floor and spine as I counted, one by one the plant hairs and leaves unfurling across the other side of my sweaty pillows. I tried to escape tendons bunched under blood and trapped in contractions. I tried to separate me from me, and unfasten each vertebra that had cracked under nerves. Those nights were loud, waiting in the feverish pain when sleep wouldn’t come, and I replayed again and again the moment when my dance partner had dropped me in my last performance. And the moment when a different man had invaded me. Both men and both versions of me quivered with me all night in bed. My arms interlocked, my pirouettes, my body washed in something I couldn’t name. My back and pelvis frail in night and violence and silence, trying to make a garden, trying to make my body less dangerous, less curved, less cracked under shadows and lamplight.

Patience

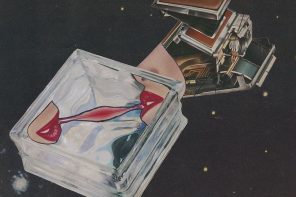

An angelic child, he trapped Locusts and Arched Hooktips into plastic nets we’d found at the Dollar Store. He waited for hours in ankle-deep water, his arms and legs mosquito bitten and burnt by the sun beating down on him like fire from a lit match. He held his breath, moving the bugs quietly from netting to a pickle jar with holes poked in the lids. A hyper kind of focus, a loud kind of focus. Something I didn’t understand about my brother. A genius, people said. He easily memorized the names of birds and bugs as he wrapped insects in paper towels without crunching their backs. He laid their death in mom’s plastic dishes once they’d gone to the other side. See how we already talked about death. All the words for the ways we stop breathing. He wrote their names with a fine black sharpie pen on yellowed masking tape. His need to please his teachers imprinted on him like the wild ducks that circled around us in our neighbor’s field. It was quilted into his skin, a fleshy kind of desire to make everyone around him proud, even if it meant a whole summer lost to proctoring the death of thousands of bugs before fastening their bodies with mom’s pearl sewing pins to dusty tile stolen from our basement ceiling. I remember his childhood body and the anxiety surrounding us both. I remember that summer as something indefinable, like a shadow I couldn’t yet name that gunned for us. I remember the Mississippi River and how quietly it rose, how none of us knew what was coming. I remember it like the smell of a dead deer that hung from rafters under our house, braced on stilts in the flood plain, as it twisted in a wet wind, its bones thin and crying out beneath us.

Jessica Freeman has work published or forthcoming in The Mississippi Review, The McNeese Review, Third Coast, Foothill Journal, Cider Press Review, SWWIM, UCity Review, Tinderbox, and others. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and has received an Honorable Mention from the Academy of American Poets and is a former winner of the Joanne Hirschfield Memorial Poetry Prize. Currently she teaches poetry at The Women’s Center in Carbondale, IL and English at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, where she is an MFA candidate. Her forthcoming manuscript is titled Songs for the Father of Waters.