We are a tangle of pale legs, our toenails painted five different shades of delicate shell pink. We sprawl in a loose circle and paint vibrant lips onto our faces, rime eyelids with burgeoning color, dust shadows beneath cheekbones, coax rosy highlights onto smooth complexions. We wipe our skin each night with washcloths dipped in boiled baking soda so we become blank canvases for the next day’s face. We check for nicks, for scratches, but we are careful. We are well preserved, and preserve each other well. We are always arranged in the same order. It is always the same arms weaving in the same pattern. The muscle memory in our fingers is shaped across the curves and planes of another girl’s face. Sometimes we believe we’re identical.

Sometimes Alice dreams she’s wearing Jennifer’s face.

We spend the summer inside. All of it spells decay: the heat, the light, the humidity. We are too intentionally made to let natural processes win out. The air conditioner’s hum is so constant that we leave space for it in the rhythm of our conversation. It gently tangles our hair.

We close the windows and pull the shades down so the slats leak yellow slices of sunlight dripping with dust motes into the room with us. We prefer the cool brightness of incandescent lights. They are steady and unchanging. When we turn them off, we bask in the afterglow, the filament fading slowly with its power source removed. It appeals to us. We see ourselves in miniature: we are afterglow, preserved.

We comb our hair with soft-bristle brushes until it gleams modacrylic, long and straight, colors ranging from chestnut to chocolate. We are always touching one another. An ankle on a lap. Fingers on a shoulder. Our voices harmonize, low and calm and cyclical.

In the evenings, sometimes, we go to parties. They like to invite us. We are good at smiling at people, at knowing when to nod at their stories. They are comets wandering in far-flung and lonely orbits, stumbling and crashing into each other for a few moments. We are a constellation. We feel their eyes slide over us. No one stays for long. We are an oasis of deliberate movement and they are nothing but frenetic. Their disorganized chatter reminds us that we prefer our own company. We never need to raise our voice. Sometimes we remember to pity them.

We spend long days in the artificial bright of the basement and compare the identical shadows from the tendons in our necks, the identical angles of our wrists and ankles. The summer air is warm and dry and calm, steady against our air conditioner. Our feet are cool against the carpet.

We like it in here. We don’t like to feel observed. Outside, it is so much easier to be just our painted faces. Outside, we are too polite to insist on being seen as we see ourselves.

We notice the stares. Waiting in supermarket checkout lines, in the aisles of a 24-hour drugstore. In the living rooms of not-quite-friends. We’ve heard the whispering: they think we’re too self-absorbed to notice them, but we have five pairs of eyes and one of us is always watching.

We never were the kind to play make-believe with tea sets. We know how they imagine us, with matching doilies and crustless sandwiches, teacups printed with pink roses. They admonish this idea of us born from their own lack of originality. But we don’t stand on ceremony when we’re alone. We dislike how our fingers feel against the fine china rims. Bones reduced to ash and reshaped with feldspar and clay, refired, cooled, warmed and animated by boiling tea. The reminder is repulsive: the teacup an identical sensation to holding each other’s plasticine hands.

We are not tired of our basement, but we know these walls too well. The argument is raised: maintaining a routine is meaningless without the possibility of deviation. Grace suggests we venture outside. The sky is a deep purple but the air is cool and dry. We wear sandals with rows of interlaced leather straps so our toes peek through the weave, only hitting shifting slivers of filtered sunlight.

We walk arm-in-arm through half-familiar streets and are surprised to find ourselves at the cemetery. No one remembers deciding to walk here. We let our hands skim the top of the gravestones and try to summon a sense of kinship with the bodies buried beneath. That was us, once. But now there is fire between us, calcination to obscure our origins and then a kiln to mimic them. Now the bodies are them and we are us, we are something new.

The winding breeze is loud enough to disperse our whispers. It feels like walking alone.

We feel observed when we walk home, away from the empty potential of the graves, but for once we find no one watching. Once home we make sure the windows are securely closed.

The next two days are sunny.

On the third day, we again wear sandals and slice through a pale gray afternoon to the cemetery. The headstones are warm this time, as though they are saying they’re more alive than we are. The ground beneath us is dry and hard-packed. We lie down on the grass between plots, careful not to stain our clothes. Ellen hums a low tune that vibrates pleasantly in our ears although we can’t quite catch the melody. We are too contained within the smooth shell of our skin. At home that evening, we are careful to wipe the dirt from our feet.

We visit the cemetery whenever we can in the following weeks. We wonder whether earth was ever disturbed here in our honor. We would like to thank that motherly once-body. We visit so often that we become accustomed to the quiet. Our voices begin to rust softly.

Mary coughs to clear her throat and suggests that we go at night. The evening is feathery dark against our skin. The faintness of the stars pulls at us and we feel pangs of guilt at the effortless connection we feel with those distant burning bodies while we’ve yet to feel anything but stillness from the dead.

On this night, the air is too full. It bursts as we pass through. We wonder how the grass would feel against our bare toes. We walk as five separate bodies, careless of the space between us. It is impossible to read our faces in the darkness.

When we arrive, everything is as we expect. Everything is as it always is. The stones, worn and crisp, have not shifted. The waxing moon isn’t bright enough to reveal more than the suggestion of headstones.

Our footsteps tattoo an artificial heartbeat into the quiet dirt. It is a soft, scattered pulse, as though our presence pulls out the land’s dying gasps. For a moment, we wonder if we are not truly reviving anything after all. Our pallid bodies flicker with movement. Without our feet, the stillness is so much more complete than we had imagined.

We wander separately through the twisting rows. We drift through the night until dawn layers gauze over the brightness of the stars. When it is light enough that the trees are more than the frayed edge of the night sky, we return home.

Alice asks if we are getting old. We have lost track of time. Soon, it seems as if we have always doled out the days waiting for nightfall. We forget to blink and our eyes glaze over. We don’t know how to answer her.

Flowers are creatures more delicate than we are. We gather them by the armful. Grace pulls a rose once by accident, and a thorn gouges the skin of her finger in brittle white flakes. We are surprised by how little it hurts. But it is deep enough that Ellen sometimes startles at Grace’s unfamiliarly rough touch, the scar snagging on her hair. From then on, we are careful to choose dry, thornless stems.

Our knees roughen as we sit in the dull afternoon light at a crossroads between rows of graves. The petals are as soft as the skin beneath our eyes. We tug them gently, gently from each calyx. We are careful not to tear their fragile smallness. Our fingers appear brutish and monstrous for the first time. We smile at this, our first chance to feel powerful, the first time our hands were put to unintended use.

We tear the stems into thin fibrous strips until they are slenderer than the drying grass. Their juice starts to stain our fingertips a pale green that will not scrub free. We feel closer to the peeled and split stems than to the petals, closer to the petals than the dead. Sometimes we remember to pity the flowers.

The petals remain in a fluttering pile like so many restless moths when we stand. The wind, we know, will be greedy enough to accept our offerings.

We begin to grow restless on sunny days, but we are not so incautious as to venture from our basement room.

On this morning, the clouds are thick and bruised and ordinary by the time we reach the cemetery. We venture out so rarely, even now, that we do not know what it means when the air smells heavy and close. We can’t articulate this premonition of difference. We are not used to difference, to change. It is not in our nature to acknowledge changes we could ignore. It is not so strange that we were unable to confront the unfamiliar scent in words: fresh, growing, alive.

Ellen is the first to say something. We can all hear the gathering in the sky. Her voice trickles up through the tumbled-down well of her throat. “Maybe,” her voice shudders out.

We know. We don’t want to say it. We do not want to admit our newfound freedom is an illusion. We don’t want to prove ourselves unnatural by retreating from the natural world.

“Maybe,” Ellen says again, or maybe it’s Mary.

And then we are running. We do not remember dropping the flowers but primroses lie crushed in inelegant heaps behind us, the petals still chained together. Our feet slap the sidewalk. This time they beat out our racing pulse, a drumbeat of panic. Rain freckles the pavement.

We converge around the front door. Alice fumbles with the key. Grace pushes damp hair out of her face while Mary keens with worry and Ellen ducks her head and then finally Alice jerks the door wide at the click of the lock and we collapse through the doorway.

And Jennifer.

Jennifer stumbles in a half second later. We notice the paint starting to dribble down her face, her dripping eyelashes, her bedraggled hair. She coughs once. The heavy wetness of the sound grates on us. A fine white powder emerges to dust her lips. We are afraid.

We wrap her in a towel and try to press close enough that she stops shivering, but she seems too fragile to touch. We are grateful for our painted smiles while we watch in horror as her skin melts down to a flat pallor. We dab at her face gently to remove the grotesque rivulets of color. She falls asleep in our arms.

It happens in a matter of minutes, and then very slowly. We dress her in dry clothes and fan her hair out to dry. Small tufts come out in our hands when we try to untangle it, but Jennifer never stirs.

For several days we creak when we move, but the air is dry enough that we are left only with the ghostly memory of aching limbs. Jennifer’s hands slip slow and clumsy across Mary’s face. We pretend not to notice the unsteadiness of Mary’s new smile. We turn off the air conditioner when Jennifer continues to shiver. Our skin starts to warm in the heat. There is an off-balance emptiness in our conversation. We hurriedly credit it to the absence of the mechanical hum rather than the pauses Jennifer takes to find a breath. Our skin is still smooth. Jennifer’s is rough and crumbling.

We stop leaving the house. We unplug the phone so it will stop ringing.

We remember, now, about the abandoned primroses. We imagine the brightness rotted into a moldering pile. Jennifer wants to check. We want her to stay inside. We assure her that they have returned to the earth. Her face twists strangely, almost as if she were trying to cry.

We are not creatures of change. None of us admit that Jennifer is changing. That she’s lost her voice entirely. That her bare skull shines through her patchy hair. We paint each other into vibrancy less and less often. We refuse to acknowledge that the five of us are no longer us. It is not so strange that we are unable to confront the unfamiliar situation in words: Jennifer is no longer us. She is she, her, separate.

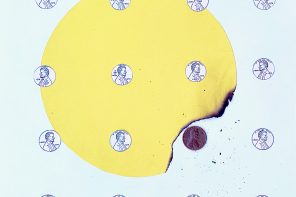

Jennifer is not sick. She is dying. We did not know that it was possible for us to die. Dolls, given proper care, do not die. They remain. We take good care of ourselves.

But. Jennifer is dying.

She coughs up more and more bone ash. She looks as though she’s been powdered with flour. Something inside her is chipped, audibly scraping, but she never complains. Her movements stiffen and slow and gradually cease. She is arthritically still but for her eyes, when she opens them.

We ask her what she wants, what we can do. Jennifer responds with a faded smile, subtler each time. Her lips are fading. Alice hasn’t painted them in days.

We start calling her Jen, as if the extra second we save will prolong her time with us. As if this were a time worth prolonging.

One morning she snaps to a sitting position and coughs. Her lungs crack with a chime like fine china. Her ragged breaths are syrupy, but she heaves dry coughs that are too deep for her fragile body to support. Her chest splinters inward and there is no air in the house. Her lips crumble to a slit and her eyelids stick, trapping her eyes open and staring. She coughs the fine white powder of herself across the carpet.

We want to breathe life back into her but we have none to give. We never have. We are afraid to touch her. We are afraid to be out of her reach. We are afraid she has forgotten who we are. The space between her sobbing breaths is deafening.

What is there to do with twice dead bones?

We are a broken constellation. Cassiopeia in constant danger of slipping from her chair. Now we are four, the Big Dipper’s broken cup falling without a handle to hang it against the sky. We haven’t yet learned how to rearrange ourselves so it doesn’t look like we’re waiting for her to join us. We don’t leave the house anymore. We don’t speak of outside.

We stop painting each other’s faces.

Alice paints blue streaks like tears. Grace paints her mouth in wide horizontal stripes, trying to color a screaming crevasse into her face. Mary caulks her eyes with browns until they look more tired than a bruise. Ellen stops painting at all and sits very still, so we can almost see the impression of her neatly folded legs preserved in the weave of the couch.

I wake up in the early hours of the night and tiptoe softly to the bathroom mirror so I won’t wake my reflection. I scrub and scrub at the unpainted white of my collarbones until it starts flaking off in a fine dry powder, until I can watch my body return to bone.

Paula Weiman is a writer with a BA in Literature and Italian Studies from Hamilton College. They have worked for many years with the Vermont Young Writers’ Conference, encouraging high school students to push themselves with their writing. They currently live in New York where they work as a literary scout.