Before all the video arcades closed thanks to the innovation of online gaming, Dad and I kept one in a little corner space between the rest of a mall and a Montgomery Ward (which was gone before we were, although the space they left was still empty). Besides the usual mall favorites like the shoe stores, fashion depots, and pretzel shops, the place was full of Filipino places catering to the large community of us in an area far from home. There were Filipino bakeries and fast-food restaurants, a barong shop, a karaoke stall, and a seafood market. Dad knew all the owners and patrons of these establishments. He was particularly friendly with the owner of the seafood market, Marie, who in turn was real sweet on me but never paid more attention to poor Dad than anyone else. Nevertheless, he was a popular and kind guy. Would rather toss some free tokens at kids than yell at them for breaking a machine. We had a small apartment by the mall, so we were never far from it. After school, I’d head to the arcade first. That was my real home. I never got into games like Dad did, but I liked getting my hands in the machines, figuring out how they worked. We had a decent life in that arcade. I couldn’t say I wasn’t happy.

When the arcade went under, Dad went with it, as if giving up the place also meant giving up who he was. He stopped working, stopped talking, stopped going out, stopped caring for himself. His friends kept calling, but he never picked up. He would just sit on the balcony and look down, waiting. Says a lot about me for not talking to him about it, or at least chaining up that sliding door to the balcony. But what could I do? Dad wasn’t the only one hurting. While he sat there, I got older, stayed out later, eventually found my own job at the mall working at the seafood market for Marie. It wasn’t like looking into Dad’s old machines, but it was work.

Dad disappeared on my eighteenth birthday. All his things were still in their place. His room still smelled like he was there. The police and his friends couldn’t do anything but tweet about it. Nobody looked for him. When I told Marie, she put me on full-time with benefits even though my hours were far from it.

“You need to think about yourself right now.” She coughed and put her hand on my shoulder.

She was always sick on account of how cold we had to keep the market for the fish. She constantly smelled like fish guts and Vick’s VapoRub.

“Your dad had it rough. That doesn’t mean you should have it that way too.”

I graduated from high school and started working the full forty a week. Still, Dad didn’t return. Why would he? I thought. Sometimes a problem just goes away.

Three years after Dad disappeared, I received your letter addressed to him. It was postmarked from Mindanao to the mall’s address, one year before our arcade closed. Marie handed it to me while I was labeling some jars and told me to take a break.

“Take your time with that,” she sniffled, standing over me, the strong menthol odor of the VapoRub and the sour smell of fish blood trailing after her like a ghost. “The jars will be waiting for you when you return.”

By then I knew more than jars. I could name and identify all the fish we had at the market. There were your alumahan, bisugo, and kitang; the popular ones like your salmon, tilapia, bangus, galunggong, maya-maya, and dilis; and your more exotic fare that only the older folks bought like your sapsap, hiwas, and lapu-lapu. There was something more fulfilling in knowing fish than in knowing the inside of a machine.

I took the letter to the break room and opened it on the table over some crumbs and a wet spot from someone’s lunch. At the top of the letter was Dad’s name preceded by the word “dear” printed in lower-case. Based on your handwriting, you were unfamiliar with what you were writing but tried to express all you could with all you knew.

Return. Recome. Relate. Respond. Goodbye.

The words were followed by strange markings. At first, I thought they might have been drawings. The shapes took the form of animals I had never seen before, but among them was a particular pattern and intent beyond the arbitrary. Towards the end, whatever was already on the table bled through and smeared the ink. I quickly lifted the paper, but the damage was done. Something I already couldn’t understand became even more indecipherable. I spent hours in the break room trying to figure it out. Eventually, it was closing time, and Marie and I were the last ones left in the mall.

“This is an invitation and a ticket home,” she rasped, clearing her throat. She proceeded to tell me that she and Dad came from the same island tucked in the rough waters of the Sulu Sea. It was far removed from the rest of the Philippines, from modernization, and from the Islamic influences in the south. Dad never spoke of it.

Marie had kept where she was from a secret, but somehow, Dad knew. From what Marie told me, there was a connection everyone on the island had with it and each other. Home was an island where there was no technology, just two indigenous tribes still living by the old ways and worshipping the old ones. I tried to imagine the island but all I could see was the arcade beyond the fish on their bed of ice. I couldn’t imagine a place without technology or even a place where fish were alive.

As for the old ways and the old ones, my father had raised me Catholic my entire life. In his room was a tiny altar nailed to his wall, a porcelain Santo Niño standing at its center. I slept with a rosary and a relic of Saint Peregrine in my pocket. But, according to Marie, the old ones were our gods. Although she and my father had learned to be devout Catholics, religion had nothing to do with the old ones. The old ones existed no matter what one believed. Some called them the Datus or the Taong-lupa, but they really had neither name nor form. Those things did not matter to them. They kept the island and its tribes safe. And, in return, the people abided by their rules.

Marie told me the story of the island’s tribes and about the consequence for leaving. Before the old ones, the two tribes, the Dumama and Jokoko, were constantly at war over fish and pearls until each commodity became scarce. The old ones, in the form of a storm, promised to provide fish and protection to both tribes if they stopped fighting and accepted their law. The tribes agreed and lived in harmony and prosperity with the old ones.

“Since then,” said Marie, “our people have kept to the island and to the same way of life they had been used to for thousands of years.”

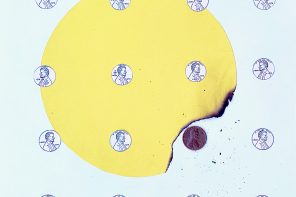

Among these traditions were two very important ones: no one could leave the island, and the Dumama and Jokoko had to intermarry to have children. The tribes were content with this until, a thousand years later, a few people wanted to leave. The old ones did not force people to stay, but there was a price for safe passage to the outside world: The person who left would have to leave behind the person they loved most and never return again.

I assumed this was how Marie ended up in the States and why she did not want to talk about it, so I didn’t pursue her reasons further. Instead, I thought about Dad and about me. When I came to the States, I was too young to remember anything before that. As far as I knew, I had always been here and never anywhere else. I had nothing else.

Marie told me that the language I could not recognize was the writing of the Dumama, the tribe she belonged to.

“I’ve had to change so much from back then in order to blend in with the people here,” she murmured from deep in her throat. I could not imagine how her people dressed or how much she really had to change. I could not imagine Marie any other way. She was always trying to fight something off, always working hard to live. It was hard to imagine her strong.

Marie read the letter and told me that you were inviting me back. She speculated that because I had not chosen to leave the island, I could return now if I wanted to.

“You can go for a visit and see if you like it,” Marie said, as if I could just snap my fingers and get there. I told her I didn’t have any time or money to go anywhere, nor did I want to visit a place so far removed from what I already knew. The seafood market started to feel humid. Somewhere far off in the mall, I thought I heard the crash of waves.

“It’s too late,” Marie said. She held out the letter and pointed where the table had stained the writing, but her voice and face were already far away. “Once this gets wet and dries, you’re already there.”

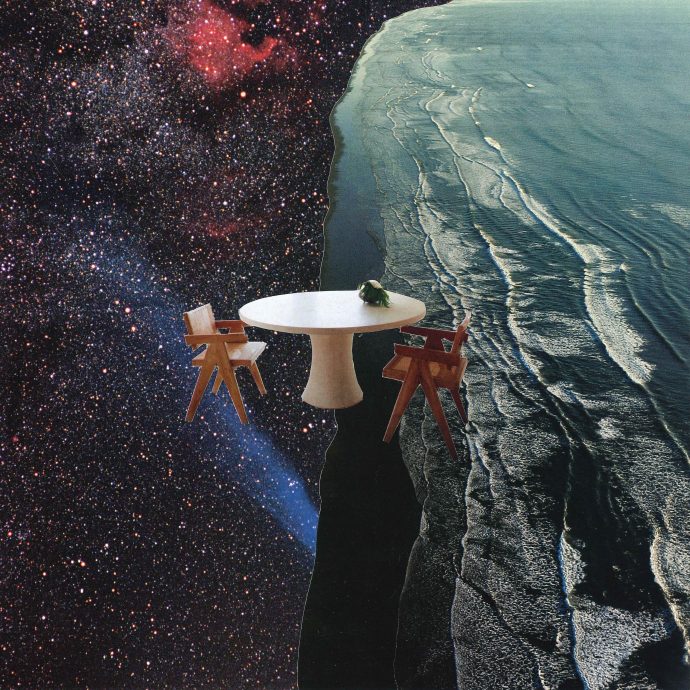

I was hit with a wall of salt water and seaweed on a long expanse of sand. I was no longer sitting on a chair with a table and Marie in front of me. Instead, I was sitting in a shallow tide, waves dancing beyond the horizon at sunset. I closed my eyes, and when I opened them again my legs were sinking in the sand, my uniform drenched below my waist. I was there on your island.

People of all ages dressed in orange and purple garments trudged through the heavy sand to meet me. I began to make out their village extending over the water, its appearance becoming more apparent in the dimming light. I got up and walked towards them, surprisingly unafraid. In some strange way, these people felt familiar to me.

At the front of the line was an old man with a vibrant headdress of banana leaves fanning out above his ears. Other than a mild slouch, his stride was swift despite his age. In fact, he moved as fast as even the strongest looking of them. He walked towards me, an inviting smile on his face, his arms raised to show he meant no harm. They all looked friendly. Reflexively, I raised my arms too.

I was surprised that I understood their language. Maybe Dad had spoken it while I slept, and it had soaked into my subconscious. They all welcomed me, repeating the words “Tabi-Tabi po,” the men slapping my back, the women wrangling their children, who were watching curiously from behind their mothers’ skirts. I saw myself in the eyes of one little boy, behind whose wonder lurked a curled yet pensive fear of the unknown.

As we walked to the village, the old man introduced himself as the chief of the Jokoko. His people had been anticipating my visit. I asked him if he had seen Dad, but neither he nor anyone in the village had seen him since he left.

“The old ones,” the chief of the Jokoko started, letting a little girl ride on his tan and toned shoulders, her feet beating at his chest, “only want to give people what they want.”

The little girl on the chief’s shoulders continued to repeat the words that greeted me on the beach. I asked the chief what “Tabi-Tabi po” meant, and he laughed, saying there had been a misunderstanding.

“At first, we thought you were one of them. ‘Tabi-Tabi po’ is what you’re supposed to say when you come across one of the old ones. You ask them to let you pass.”

I asked the chief if he’d ever met a god, and the chief shook his head. He said that if he were to really meet a god, words would be unnecessary.

The village was made up of densely clustered huts strewn across the shoreline and over the sea. The huts over the water, each occupied by an entire multi-generational household, were connected by plank and bamboo stilts. The reflection of the setting sun on the ocean’s surface made it nearly opaque, but underneath I could see teaming shadows of life. The waves thrashed and rippled, but despite this frenzied activity, there were no fishing boats on the water.

All the work was done on land. Trays of dilis and hiwas lay salted and drying in the sun. Skewered lapu-lapu and blue crab hung over an open fire while rice steamed in banana leaves elevated far above clay furnaces. Young men and women cut freshly gathered herbs and vegetables, the smell of mint, cilantro, kalamansi, ginger, and an assortment of colorful chili peppers distributing a pungent smell across the harbor.

As we traversed farther into the village, I grew curious about the Dumama and asked the chief where their village was. The chief touched his heart and said they were all around us, and I assumed he meant there was no distinguishing the tribes from one another. I told him about how I met a member of the Dumama and a glint of surprise showed on the chief’s face before he covered it up with a smile.

“They only come out at night,” he said and didn’t speak again until we’d made it to his hut, the one farthest out in the ocean.

Nearly a hundred people filled the chief’s hut, bringing enough food to feed three times as many. The chief and I sat on cushioned seats at the main table while his people served us. From what I could recognize, there were the dried dilis and hiwa, grilled blue crab and lapu-lapu, and fresh, creamy sea urchin. I gorged on the smoky, salty taste of the freshly cooked fish. It was the first time I had really enjoyed eating it rather than looking at it. Had that been all the food I ate, I might’ve already been satisfied, but then a steaming pot of stew puffing with the aroma of chili peppers, coconut, and fatty fish made it to our table. The chief told me it was a nameless delicacy made to honor the old ones. The savory, sweet, and spicy sauce blended perfectly with the milky bangus and salmon-like fish melting in my mouth. With the salt of the ocean breeze brushing my lips and stinging my sweat-drenched skin, the stew seemed to envelope me more and more, bowl after bowl. By the end of the night, the pot was empty, and the hall was cleared.

Still, the Dumama had not come. Food was put aside for them and brought to another hut for later. According to the chief, their absence was no surprise; the Dumama were very shy, especially with visitors. Hiding my disappointment, I apologized for inconveniencing them and helped him put together my makeshift bed of mats and wools. I told the chief that, although I appreciated his hospitality, I had already decided to leave in the morning. In the dark, I could not see him, but the unwavering kindness in his voice assured me that the Jokoko would respect my decision.

We settled in, but sleep did not come. My mind fixated on the sound of the water hitting the bamboo and thundering up and down the coast and far beyond the island. There was so much I did not know, and I was too curious about it to sleep. I quietly made my way out to explore. Outside the chief’s hut, I was met by the unworldly sight of the moon and the stars streaking across the heavens like sand scattered across a dark palette. The entire village was asleep and blanketed by a celestial glow. For a long time, I stood at the door, looking up.

Then, out of the corner of my eye, I saw shadows flitting in the water. Although its surface reflected the sky, the water had become semi-transparent in its light. I stepped closer to the edge of the pier to take a look and was met with the splashing of large fins. At first, what I thought I saw were large bangus or yellowfin teasing the surface. Hundreds of dark outlines slowly made their way in every direction under the pier and beyond. However, the more I studied them, the more their fins appeared as limbs, the more their gestures became a language.

Then, suddenly, I saw them. Beneath us was an entire village of these beings working under the water, plainly visible in the penetrating moonlight. They searched the ocean floor on two legs, swam quickly after fish, entered and exited cavernous holes in the ground, and greeted one another. Although I could see their gestures and shapes, their exact appearance and intentions were still unclear. I wanted to continue studying them, but the more I tried to look, the more my knees weakened and heart pounded. Eventually, it became too much. I backed away from the pier, hearing only the sound of my blood pumping, my staggered breathing. I crept back into the chief’s hut, so as not to let my absence be discovered, but you were already there, standing where I had been sleeping.

In the moonlight from the window, I noticed your glassy eyes first. They shined like two giant pearls protruding from the sand. Startled, you stood straight, revealing your tall and slender body covered in scales and gill. Your hands and feet: webbed and clawed. And your face—your face petrified me. Where a human would have their nose, mouth, and chin, your tentacles sprawled and coiled like they had minds of their own.

Then there was the familiar smell, the one of dead fish, the pungent odor I had come to associate with Marie. Somehow, I hadn’t noticed until then, but the smell had been there in the village. You had been there.

In whatever tremulous voice I could muster, I asked you if you had written the letter and if you had taken my father. You made a noise I could only understand as a chuckle. It was guttural and hoarse like when Marie tried to talk. Somehow, it put me at ease. You began to move toward the door, beckoning me with your claw. I followed, checking on the sleeping chief as I passed. He was snoring quietly.

Trembling, I watched as you peered over the water. You beckoned me again. I stood in the doorway before mustering enough courage to push myself forward. I took my place beside you and looked down. At first, I saw what I had already seen. Life went on under the sea, your people going about their lives like a silent film. But then I caught it, above the water, in the reflection of the moon and stars. The silhouette of two people gradually began to fill in. Suddenly, I saw what you had been looking at, what you had been trying to say. Beyond what I thought you were, there was something I had missed. A familiar flush in your cheek, a recognizable narrow arc above where your mouth was supposed to be, a unique and habitual twitch where your tentacles curled. We had both inherited what our parents left us. You were Dumama and I was Jokoko, but those were just names for what were practically the same. We nodded at each other and, as if confirming that I understood you, you slowly dropped back into the water, blending in with everything below and above us. I went back to bed and, in the morning, I left without saying goodbye, which was Dad’s way of leaving.

Somehow, I came home, but I realize now how much your invitation meant to me. Dad still hasn’t come back, and I don’t think he ever will. I feel like he left me a long time ago, before he even stepped off your island. I think, had he the chance, he would have taken you instead. You knew that, didn’t you? You have that in common, you know? Sacrifice.

Still, I know the likelihood of this happening is low because I know how difficult it is to give up all you’ve ever known and loved, but, on the off chance you do, on the off chance this reaches you and you find yourself wondering, if you find yourself in the States, don’t hesitate to stay with me. You have family here and wherever I go. I’ll be waiting.

E.P. Tuazon is a Filipinx-American writer from Los Angeles. He has published his works in several publications, most recently Peatsmoke Journal, Third Point Press, 3Elements Literary Review, In Parentheses, Five South, The Dillydoun Review, and forthcoming in The Rumpus. He also has two books, The Superlative Horse and The Last of The Lupins: Nine Stories and The Comforters. He is currently a member of Advintage Press and The Blank Page Writing Club. In his spare time, he likes to wander the seafood section of Filipinx markets to gossip with the crabs.