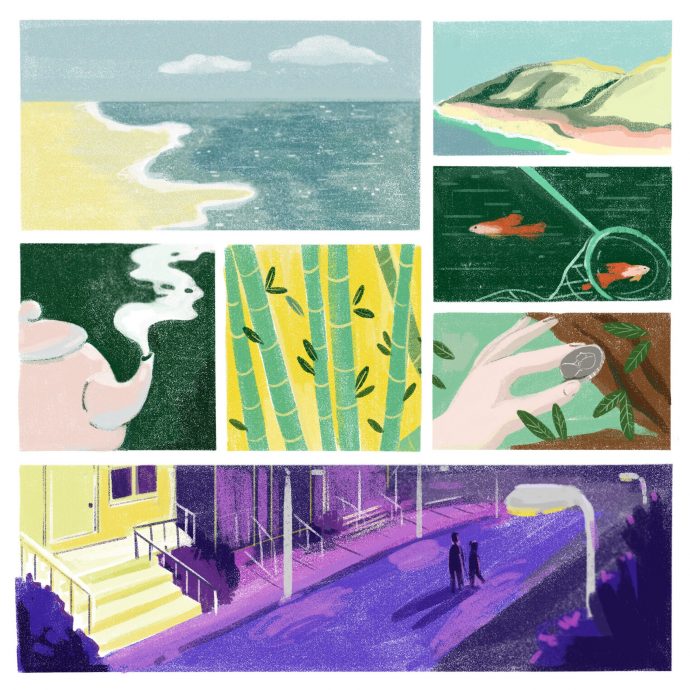

MY BROTHER, IN EIGHT PANELS

They say he looks foreign, my brother. They say he steams kale. They say he eats as he walks: lunch hour, shoving a burrito into his mouth. They avoid saying hello at these times. They say he never wants to return home. Was it the sun pouring into his cement-walled room all through our childhood? They say he is happy with the distance that oceans make.

With the distance that oceans make, over the remains of a dinner that we have eaten too quickly, in a B-rate Malaysian restaurant, we try for a pleasant conversation: work, his dog, cellphones, media, his dog again. He slouches back into his chair, jabbing the table with the tip of his hashi. I’ve leaned back too. The waiter brings another pot of tea. For a moment, we both watch steam rise from the spout.

Steam rises from the spout of Grandma’s teapot. My brother ducks under the table and scoots past the tangle of chair legs. I follow, bowing “Gochisosama!” and race after him. In the yard: “Look, that tree has sprouted pennies,” he says, plucking a coin from the bark crease. “Wow, a dime!” I call, pointing to where I had wedged it just that morning. It is a fine trick. We search the bark until the night comes shuttering our eyes. My brother pats the trunk and says, “Thank you, money tree.” I marvel at his gullibility. He walks away jangling pockets full of my change.

With pockets full of our father’s money, we make for the pier. We are not elegant, but I have just emerged from my first year of college, so we will eat in the finest restaurant in town. The Puget Sound makes quiet waves. “If you only had twelve hours to live,” he says, “I would take you to meet this famous poet. I don’t read that stuff, but most people know of her.”

“I suppose that is when poetry matters most,” I say. “And what would you do? If you only had twelve hours?”

“I would tell off everyone who has been an asshole to me.”

We watched each other over the cutlery.

We watch; we are each other’s keeper of time, of those past selves running through the bamboo forest or catching guppies with green nets. Somewhere still we are marching through the house singing the appleskin song. We are mid-summer, scratching rock drawings. When I say that I don’t know him, it’s not true. And yet, what do I really know?

What do I really know? At sixteen he took a pickax and swung it high above his head. Swung it unskillfully, but with strength. His arms were too long for his body then. The pickax made a great arc before coming down on the money tree. Its branches snapped too easily, so he bludgeoned a boulder, the one I thought looked like a dinosaur’s head. He hit it again and again, gouging white dust from the rock.

From the rock, from the crucible of deadline and fever-stress, my brother shapes his genius. From catastrophe, from breach, from the buzz of almost-ruin, my brother plucks just the right words. How he works. How he works. “Hi. sorry can’t talk at work.” Years of silence, then just the right words, thrown down to me like crumbs: “I’m proud of you. I hope the rest of us can learn from your kind soul.”

I hope the rest of us can learn what to do with these rinds, these scraps; I am always starving with you. Oh, my brother, my beautiful heretic, what else is left for us? This street? Its yellowing light? The corner where you chipped your tooth and I held your chin, bloody, to peer up into your hurt. Brother, I know you do not read poetry. Still the day ended here. We walked home in silhouettes, failing indigo. Porch lights flickered on. We moved deeper in, farther away, tending the silences in our own feral minds.

With the distance that oceans make, over the remains of a dinner that we have eaten too quickly, in a B-rate Malaysian restaurant, we try for a pleasant conversation: work, his dog, cellphones, media, his dog again. He slouches back into his chair, jabbing the table with the tip of his hashi. I’ve leaned back too. The waiter brings another pot of tea. For a moment, we both watch steam rise from the spout.

Steam rises from the spout of Grandma’s teapot. My brother ducks under the table and scoots past the tangle of chair legs. I follow, bowing “Gochisosama!” and race after him. In the yard: “Look, that tree has sprouted pennies,” he says, plucking a coin from the bark crease. “Wow, a dime!” I call, pointing to where I had wedged it just that morning. It is a fine trick. We search the bark until the night comes shuttering our eyes. My brother pats the trunk and says, “Thank you, money tree.” I marvel at his gullibility. He walks away jangling pockets full of my change.

With pockets full of our father’s money, we make for the pier. We are not elegant, but I have just emerged from my first year of college, so we will eat in the finest restaurant in town. The Puget Sound makes quiet waves. “If you only had twelve hours to live,” he says, “I would take you to meet this famous poet. I don’t read that stuff, but most people know of her.”

“I suppose that is when poetry matters most,” I say. “And what would you do? If you only had twelve hours?”

“I would tell off everyone who has been an asshole to me.”

We watched each other over the cutlery.

We watch; we are each other’s keeper of time, of those past selves running through the bamboo forest or catching guppies with green nets. Somewhere still we are marching through the house singing the appleskin song. We are mid-summer, scratching rock drawings. When I say that I don’t know him, it’s not true. And yet, what do I really know?

What do I really know? At sixteen he took a pickax and swung it high above his head. Swung it unskillfully, but with strength. His arms were too long for his body then. The pickax made a great arc before coming down on the money tree. Its branches snapped too easily, so he bludgeoned a boulder, the one I thought looked like a dinosaur’s head. He hit it again and again, gouging white dust from the rock.

From the rock, from the crucible of deadline and fever-stress, my brother shapes his genius. From catastrophe, from breach, from the buzz of almost-ruin, my brother plucks just the right words. How he works. How he works. “Hi. sorry can’t talk at work.” Years of silence, then just the right words, thrown down to me like crumbs: “I’m proud of you. I hope the rest of us can learn from your kind soul.”

I hope the rest of us can learn what to do with these rinds, these scraps; I am always starving with you. Oh, my brother, my beautiful heretic, what else is left for us? This street? Its yellowing light? The corner where you chipped your tooth and I held your chin, bloody, to peer up into your hurt. Brother, I know you do not read poetry. Still the day ended here. We walked home in silhouettes, failing indigo. Porch lights flickered on. We moved deeper in, farther away, tending the silences in our own feral minds.

DRIVING TO THE NORTH SHORE, I IMAGINE MY BROTHER

not estranged, but there with me as the ironwoods along the highway lace a brief tunnel - eclipsing the sky - then breathe us out again. Red dirt loose in the fields where the pineapple grew, where sugarcane, where our grandparents sang hole hole bushi: My husband cuts the cane stalks, And I trim the leaves – Slipping down the hill from Schofield Barracks to the North Shore, the road twists. Crosses punctuate the millage. My brother lifts his feet from the dashboard and turns to look at me. His gaze is gentle like the folding valleys of the Waianae range. And he is not looking at me, but at the peaks, remembering, perhaps, that hike to Peacock Flats – how we barely made it, scrambling, holding our rubber slippers in our hands. And finally the view from the top – the whole coastline from Ka‘ena Point to Haleiwa. The waves breaking offshore. The great blue welcome of horizon. I remember it vividly – a fluke of childhood because, in truth, I was not there. My brother stood alone, panting, victorious, looking down at the patchwork island, at the stories he wove for a sister who would believe anything of him.

Laurel Nakanishi is a poet, educator, and author of the book, Ashore. She was born and raised in Kapālama (O‘ahu, Hawai‘i) and has been fortunate to live in Nicaragua, with a scholarship from the Fulbright Foundation, and in Japan, with a fellowship from the Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission. Her poetry and essays have appeared in various literary magazines and a prize-winning chapbook, Mānoa|Makai. Laurel received her MFA in poetry from the University of Montana and her MFA in creative nonfiction from Florida International University. She currently teaches poetry to children on the island of O‘ahu. www.laurelnakanishi.com