On a Saturday in early November, the last, brittle oak leaves skittered across the parking lot of Verona High School. The stars above North Jersey were growing precise in the afternoon gloam. The final matinee performance of Putty: The Musical was halfway through.

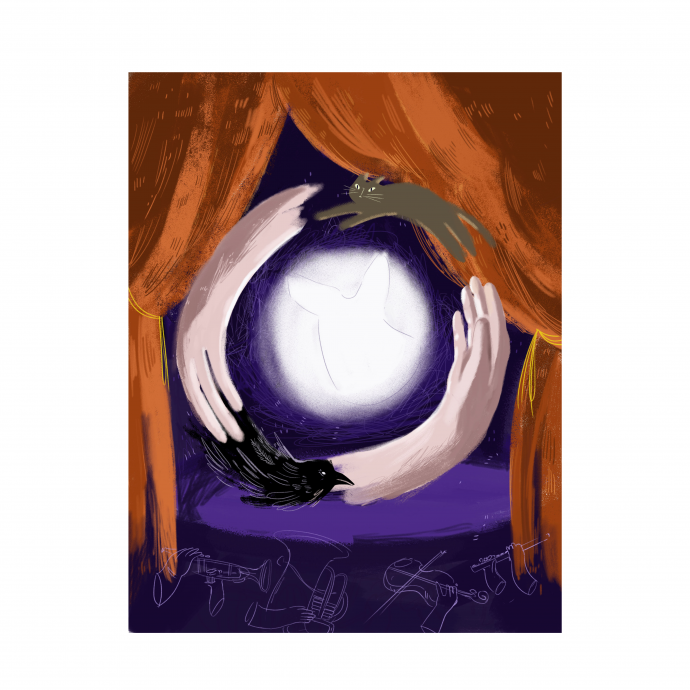

Inside, the stage and overhead lights went bright and dark, bright and dark to signify that the students were ready. Parents and guardians, extended relatives and classmates purchased their final homemade treats, gathered up handbags, and tossed their sugary saran wrappings. In the dimming room, the pit orchestra lamps became sharp little wedges of light. Beneath them wiggled the disembodied fingers of musicians. The stage curtains, long faded by sun bleach and dust, were returned in shadow to a rich crimson.

A perfect night! Biju Fetsman, Head of Art and Costumes, was in their element. Behind the curtains and in the wings, the magic of Backstage crackled: students in stagehand black transformed living rooms into corner stores and cloudless skies. Orchestra re-tuned. The Costumes dressers carefully zipped actors into ravens, reset footlong cat whiskers with curling irons. Biju left their domain for a moment to peek out at the packed audience. Beyond the stage lay all manner of troubles and worries. They wondered for a moment whether their parents had come at all. One worry tripped another. Even if they did come, would Biju’s parents know what Biju had made? And if they didn’t come, what new disaster awaited Biju at home? No, not now! They returned to the fray, where a Lighting Crew trainee practically started to cry when she saw Biju. Some prop or other had been misplaced. Could Biju find or make something else real quick?

How stifling, how hot it was! How long the play went on! Cole Fetsman, two rows from the back, was exhausted, but they had come to see their second child Biju. The school’s faulty radiators, the searing stage lights, the sweaty exuberance of teenagers calling out friends’ names at each new character’s appearance. It all left Cole faint. They had considered several times whether they could make a quiet escape. Little One had squirmed around her creaking seat throughout the entire first half, making requests to go outside. Only now had she quieted, seated on the cement floor and playing with felted dolls of squirrels and bunnies in a soft, Velcroed sack in the shape of a log.

Despite her background in arts education, Milde, Cole’s partner, had not shown. Not that Cole had expected her to. Milde had been suffering with chronic pain for years, a pain only amplified when she lost her legs due to a separate chronic illness. Before the pills, Milde was playful and creative with the children. Cole often came home to costumes made of mud and flowers, short performances the children had scraped together from their favorite storybooks and television programs. Biju and Matt, and eventually Little One, were kept on a loose leash, something unnatural to Cole. They watched their children flourish under Milde’s encouraging eye and found themselves in the unfortunate role of Parent who Hoses Off Joy.

During the interminable wait of Milde’s amputation surgery, some nurses showed Little One the 3D printer that would create Milde’s new legs. For weeks, Little One was enthralled: touching the legs, smelling the legs, and squeezing in between Milde and the back of the couch in order to compare the legs to her own tan little matchsticks. Milde groaned and swatted at Little One slowly as though she were underwater. The family had hoped that maybe the dramatic change would burn off the fog that had settled over the house. But when the medications wore off, it was clear that the old pain had only compounded.

Irritable, couch-bound, and resistant to physical therapy, Milde took leave from her teaching position for one year, then two. Passive media consumption filled her head with suspicions and melodrama, leaving little room for the life around her. Cole worked overtime to pay off their impossibly large hospital bills. Nightly they were welcomed home by a litany of complaints from a drugged-up Milde, the children unfed and fighting. At first, Cole worked extra because of the debt, but eventually they did it for the time away from home. The fridge was not empty, they reasoned. The children could feed themselves.

When Cole eventually moved into a one-bedroom closer to work, they took only Little One, leaving Biju and their older sibling Matt in their original school district. It was a temporary move, Cole told Milde. Not a separation. They had meant for it to help the family get through this rough patch.

Over the cheery intermission music, Cole could hear Little One’s whistling breath through her nose. They watched as other families moved through the aisles like fish in a narrow aquarium, winding around one another, smiling at friends and occasionally catching Cole’s eye. Parents stopped to make small talk with one another. The sounds of the room blurred. Cole stayed in their seat and pulled their mouth and eyes into a tense smile. They could no longer hear anything through the thick glass seemed to separate them from everyone else.

Behind the stage curtains, the chorus line began the eerie, wordless introduction to the second half of the musical. At the orchestra director’s cue, the chorus burst from oohs into song.

“Raven comes and goes when asked. Numen gives them one more task. ‘Watch what Putty does today.

Report to me,’ old Numen says.”

Putty: The Musical was about three years into its Broadway run and responsible for the recent repopularizing of its namesake parable. The story begins with a critical mistake: a god-like figure named Numen creates a person of putty but forgets to teach them to love themselves. In order to catch and sustain the attention of a love interest made of paper, Putty changes their body to such a degree that they become completely reflective, and thus invisible.

Many critics credited Putty’s newfound relevance to the digital natives who spent most of their time curating and performing false versions of themselves. To many of the students and audience members at Verona High, Putty was relatable because Putty sought bad love wherever she could find it, no matter the cost.

“With all of their Numen friends

Numen works until day’s end.

They’re so busy; will they send

Help to poor young Putty?

Ever since she came to life

All Putty has known is strife.

Loneliness, and self-hate, too.

Oh, Putty, What’s to come of you?”

Biju, flashlight between their teeth, flitted in the dark, from Lead Numen to Cat and Raven. Raven’s costume was the most challenging, as the student inside was slim and pliant as a blade of grass. Bram bore his feathers regally, but the heavy black beak was limiting his mobility. From under his mask, Bram’s voice was barely audible.

“It keeps slipping down…Can you even hear me?” Biju pulled back Raven’s helmet, so the beak angled upward. Bram’s face beneath was a stark, fearful white. Biju reached into their apron and pulled out a jar of pink-grey feather balm. Oh, Bram, thought Biju. He should have been cast as the paper person!

“I’m just taking down the bright of your face,” Biju said. “Keep the helmet at this angle.”

Cole’s shoulders, neck, and back ached. They weren’t quite sure what to look for. Biju had mentioned something once about costumes or sets, but would they also appear on stage?

Cole was hopeful for Biju, who may have spent enough time away from the house to not have been infected by Cole’s screaming with Matt, the terrible silence between Cole and Milde, and Milde, who slept days on the couch, tumbling forward into glowing screens in the dark.

But Matt! From a young age, maybe twelve or thirteen, he would sneak out of the house to spend his nights smoking cigarettes and marijuana and drinking beers with friends. At the beginning, Cole worried over whether Matt’s friends were the type to escalate mild rebellion into something more permanent, more brain-scrambling, more illegal. Now, nearly seven years since Matt’s first junior high detentions and police warnings, Cole was far too busy with Little One to fuss over their fully-grown Matt.

Biju whisked off to gather the next scene’s costume rack.

“Putty’s gone even more reflective!” Bram’s voice reported from the stage. “I believe it’s to attract that love interest of hers, that guy made of paper! Everyone knows he loves anything that shines. Like a seagull.”

“This is all my fault,” said Numen. A wavering major-7 chord hung over the pit orchestra. At the twitch of a baton, the clarinet tripped a gloomy half-step lower.

Putty was still offstage, surrounded by a glue-gun-wielding art crew. The bright foil shards now attached to Putty’s burlap costume reflected magenta gel lights. The student playing Putty practiced shrugging half-heartedly as she mouthed her lines. She waved off the art crew, who had been picking from her spidery wisps of glue.

“It’s fine, it’s fine,” the student said with a confidence her character would never muster.

The actors and crew all worked as a team now, but once the play and final celebrations were over, the student actors would pivot to their next seasons in Mock Trial or Debate Team or Winter Track, sharpening their tongues and developing lean muscles that would carry them to independence, healthy careers in the city, suburban families of their own.

The students who went on stage had clear, confident voices and good posture, teeth that shone in the spotlight. Biju and their slouching crew worried on the fringes, buttoned the stars into new bodies and hissed well wishes as their peers jetted onstage electric with adrenaline. The audience oohed and ahhed over emotional vocal performances. In the wings, Biju watched silently. They could see a thin slice of the crowd from where they stood, and for a moment thought they had glimpsed their parents sitting together in the center section. It was a couple that looked very much like them, but when one turned her beaming face just a little bit, Biju could see that they were someone else’s family.

Matt, their older sibling, hadn’t been at school for weeks now. Biju knew Matt had been into something particularly bad lately, information they had gleaned from Matt’s feverish late-night phone conversations and the confidences of Bram, whose older cousin hung out with Matt. Apparently a group of them had a too-wild night. Biju had been under deadline, hand-stoning a special costume nearly every spare moment of their day and couldn’t afford to get entangled. Matt was always getting into trouble. Biju was just trying to enjoy their last year in high school and devise a future into which they could climb.

“Numen’s Song of Regret” segued into the sinister “Barista’s Theme – Instrumental.” The curtains closed, and a team of stage hands wheeled the set around to reveal Putty’s home, the Pottery Studio. Street signs, large potted trees, and a garbage can were positioned upstage. The curtains opened on a tattooed Barista in leather shoes and dark, slim-cut denim, flirting with members of the chorus line dressed as townsfolk. Putty’s hand grazed the glass door of the Pottery Studio, and she began to sing in a sad, quiet voice.

“Will I ever find love?

Barista’s got love.

Those people o’er there have love.

All up and down the street there’s love.”

Putty’s voice grew louder, and the orchestra accelerated just a little. Putty looked up at the lights, gestured broadly, and put some stomach into it.

“But who’ll love an old lump like me?

Someone whom paper people can’t even see?

When your paper lover begins to stray,

How do you keep the pain at bay?

You whiten, brighten, put on a smile,”

Putty gestured at the scraps of foil hanging off of her like a tattered coat and slumped. “Try to change, and take your mind off them…”

The orchestra decrescendoed into nothing.

“For a while,” sang a foil-covered Putty acapella, beginning to cry.

Little One didn’t know how to whisper yet, and asked in a high clear voice, “Who is that?”

Some audience members turned around and smiled at her. Little One was standing in her chair, face glowing in the dark.

“It’s a person named Putty,” whispered Cole. “They’re feeling sad right now.”

“But why they’re feeling sad?” asked Little One.

“They’re sad because they’re feeling a little lonely,” whispered Cole. “Don’t you sometimes feel sad?”

“No,” said Little One, sniffling. “I don’t like it. Why they don’t want to be with their friends?”

“Sometimes Putty needs to be alone,” said Cole, trying now to keep Little One from opening into a wail. “But you know, Lil, this is just a story. Like in your books.”

“This story makes me sad,” Little One was crying now. “I don’t like it. I don’t wanna be sad. I don’t like this story!”

The people who had smiled back at Little One were growing impatient. Cole picked up a sobbing Little One so her face was over Cole’s shoulder. They rooted around on the floor for the little animals that had spilled from the log-shaped carrier. When Little One began to wail, Cole passed her a chipmunk in a pink apron, which Little One proceeded to drop from her limp hand. Cole sorry-sorry-sorryed their way down the row and fled through an impossibly loud, creaking back door.

Biju called into their walkie talkie for their lead art crew members. It was time to prepare Biju’s opus, Putty’s last costume change: the Reflective Suit. The hand-stoned and mirrored bodysuit would be the grand finale of Putty’s desperate attempts to sparkle enough to attract the attentions of her love interest. For months, Biju had been transporting the bodysuit everywhere in an opaque white garment bag meant for wedding dresses.

Because their phone was on silent, because their work of three months was about to make its final breathtaking appearance on stage, Biju didn’t know that chaos had erupted at home. With the help of two other art crew members, they dressed Putty in her final garment and cloaked it in an oversized rain slicker so as not to reveal the bodysuit prematurely.

Putty took her position in the dark and let the jacket fall to the floor. The spotlight trained on her was switched on. Several audience members gasped, and somewhere, a small child shouted, “Look!”

What a sight to behold! From a distance, the bodysuit was a fractured moon, winter-bright. Putty looked left and right for her love interest, showing off Biju’s fine detailing. Square disco ball mirrors slid up and down Putty’s limbs like rivers. The rhinestones at their banks increased in size the further away they drew. This bodysuit was no mirror to society, no erasure of poor young Putty. Biju’s work was almost geographical, as large and powerful as Putty’s faith in love. Thanks to some last-minute budgetary assistance, Biju was able to attach to Putty’s shoulders a fringe of long Swarovski pendants. The epaulets slung rainbows across the walls and ceiling of the auditorium, suggesting, Biju hoped, a dignity in Putty’s optimism amidst a world which again and again refused her respect and care.

The paper figure had missed dates before, but this was supposed to be their “Shall we try this again?” reunion, scheduled on the one-year anniversary of their first meeting. Putty had worked diligently to be as beautiful as possible for their evening together. She checked her watch again and again in an agonizing silence. When disappointment finally felled the actor onto a bench, the gesture revealed an intricacy of form. From her knees radiated stars. From her chest, a spiraling of tiny round mirrors. At the end of their process, Biju had taken care to stone by hand the bodysuit on a bespoke dress form, filling in gaps with geodes chipped like ice, layered and set by permanent glue. Sequins were sewn with silver thread and stacked like shingles, giving a structured silhouette to Putty’s form. Though forgotten by her paper love interest, Putty held within her the seeds of growth. According to the story, this reflective adornment was her creation. Loosed from the yoke of unrequited love, what wonders could she make?

With Little One occupied by a crumbling brownie, Cole was able to watch the scene through a back door propped open by a kind bake sale parent. Cole was overcome by a wave of emotion. That was what they had been watching for! That magnificent suit was made by their child. Cole squinted and tried to take in Biju’s handiwork, but Putty was so bright they couldn’t look directly at it.

At this point in the performance, all plot fell secondary to the spectacle that was Putty’s transformation. The paper person was being played by a student waiting behind stage left and sweating through their white sheet. The faint blue and red notebook lines were visible, but the moisture coming off their body was spreading dark stains over their belly and backside. Finally, their call came, and the paper person walked onstage arm-in-arm with a wax character covered in flecks of gold leaf. They walked all the way across the stage without so much as noticing the mirrored Putty. Putty, the ball of light, dropped to her knees, and “Numen’s Theme” was played at the pace and style of a dirge.

“There’s so much I wish I’d done differently,” Numen’s voice reverberated across the auditorium. The student playing Numen stood beside Biju as they recited the final lines of the show. “But most of all, I wish that I could make you new again, so you could learn how perfect you are. I’m sorry, dear, young Putty. I am so sorry.”

Like that, the show was over. The whirl of curtain calls was over. Within an hour the actors, sparkling with adrenaline, were back in street clothes. The auditorium was empty. As Biju approached their friend’s car to celebrate a job well done at the Princess Diner, Little One, rejuvenated by the crisp air, called out in the evening dark. “Biju, Biju!”

Cole was full of pride for their middle child. Their face was warped and reddish from having cried in the hall. They hugged Biju stiffly.

“You did a good job. Really, very good. The suit. It was beautiful.”

“Thanks, Cole.” Biju was radiant, a moon. “Thanks for coming.”

Someone inside a minivan full of teenagers honked the horn. The windows were open, and the sound of merriment echoed in the little parking lot.

“What are you doing now?” asked Cole. “I was thinking we could celebrate. I could take you and your sibling for an ice cream.”

“Oh,” said Biju. “The only thing is, I’ve got the suit in there.” They gestured to the van. “I think we’re going to stop by Princess.”

“Oh, yes,” said Cole. “Of course. Well,” they looked down at Little One. “Little One, how bout we go get an ice cream cone? Since you were such a good audience member.”

Little One shouted something in the affirmative and leapt up. Biju patted her head and said goodbye. Soon enough the minivan was motoring away.

At the Princess Diner, the cast and crew took over an entire section of booths. They were raucous with joy and made many toasts with their floats and sodas and free-refill coffees. Each senior got a round of applause and gave a speech, including Biju, who was popularly considered someone who could really make it on Broadway, maybe do costumes or set design. Biju’s face flushed with pleasure, the audiences’ response to the bodysuit still fresh in their memory. At school Biju was dubbed “the quiet kid.” Tonight, they basked in the attention and admiration. The George Washington Bridge, with its suspended strings of light, had stretched out its arms straight to Verona. The Hudson River shrank to a single penciled line, and 42nd Street unfurled west, a long red carpet. The future really could be just a bus ride away.

Members of the art, sound, stage and pit crews sang variations of the musical’s numbers, making up inappropriate lyrics, dipping sliced pickles into pink ice creams and feeding one another fries.

As soon as the car pulled up to the house, Biju could tell something was wrong. Not because they could hear the screaming (it was too loud in the car to hear anything outside). It was because of all the weird shapes on the lawn. Biju looked up at Matt’s open, second-floor window and watched as Matt’s silhouette threw a television out of it.

“Dude…” said one of Biju’s friends. The television landed in a bush, then bounced and landed in the grass of the front lawn.

“Oh my god!” said another friend.

Biju gathered up the bridal gown bag that contained their delicate hand-stoned suit. “I’ll be fine. My brother’s just like this sometimes.” When everyone in the car asked if Biju needed help, Biju waved them off.

“You know families,” they joked as the door to the backseat began to slide closed. “Your average Sunday.”

The car lingered for a moment before it drove off. Had they turned to see their friends go, Biju would have seen their faces, wide-eyed and yellowed by the single street lamp at the end of the driveway, watching Matt toss into the night books and binders and plastic water bottles.

Instead, Biju moved toward the house. Papers fanned out into the air, scattering as they caught the wind. Some, Biju noted, slid gracefully onto the lawn like flat airplanes.

“Matt!” called Biju. “Matt, what are you doing?”

Matt didn’t respond because he was shouting nonsense. From the lawn, Biju could hear the sound of Matt moving something heavy across his floor.

“Biju?!” called Milde from inside. “Biju, come quick. Your sibling!”

Biju slowly approached the house, not wanting to bring their bodysuit in its white garment bag into the fray. They opened the door to find Milde sitting on a kitchen stool at the bottom of the stairs leading to Matt’s bedroom. She was flushed and blotchy.

“Biju? Biju! Should I call the cops? Your sibling is going crazy. I think he’s going to hurt himself!”

“I think he’s just throwing things out the window,” said Biju.

“And then?” asked Milde. “What if he jumps out? Shouldn’t we just call the cops?”

Biju told Milde they needed to de-escalate, a word they had learned in health class.

“Well, can you restrain him? Or something? Someone has to do something. Your other parent isn’t picking up their cell. It probably isn’t even on. And look!”

She pointed out the front door, which Biju had left open. Clothing was falling onto the lawn like snow slipping off the roof. Undershirts and socks were white birds swooping out into the night.

“Let me get him,” said Biju. They bounded upstairs and stood in the threshold of Matt’s room. It was utterly destroyed. Music equipment, loose dresser drawers, furniture fragments, a broken glass and plate, childhood toys and bedding, all lay in a heap like the city dump.

“Matt?” said Biju. “Hey, sibling.”

Matt pounded his forehead with his free hand, squatted with his feet on the floor, torso tucked against his thighs.

Biju looked down at their garment bag. They would just hang it up in the closet and come right back.

“Don’t you, if you think you’re gonna get away like, well I’m gonna. No, you gotta understand that this is not gonna fly. This is the last, they can’t just, and blame me? Leave me in the, No, I—”

“I’ll be right back, Matt. Matt? I’ll be right back. Just sit right there and we’ll talk this out.”

But in the time it took for Biju to hang their garment bag in the back of their closet, Matt’s voice had gone screechy again, and then something huge scraped against the floor and there was a dull thud outside. All the while Milde was calling from downstairs for someone to do something.

The mattress was on the lawn, and by the time Biju had crossed the room to get a hold of their sibling’s arm, their sibling was on the lawn, too. Not on the mattress, unfortunately. Matt was groaning and trying to get up, even though his arm didn’t look right at all, the way it hung out of his shirt sleeve. Biju watched from Matt’s window as he went off into the night, his cracked phone screen flickering in and out of view as he ran off, still ranting.

This was not the last scene Matt would cause in the coming months. At the winter pageant (decor by Biju), rumor would spread quickly that Matt had shown up during Lunch drunk in a nightgown. Matt threw up at the foot of the high school flagpole, and Biju worked on an AP Art portfolio based around the theme “Trash says, ‘I do.’”

Matt got and lost a job at the same grocery store where Biju worked a short walk from their house. Biju stitched life-sized brides from old towels and made a series of shadow boxes, little chuppahs and paper flowers for taxidermied rats in tuxes. For the 2D component, they used white spray paint to stencil wedding vows onto stained XXL white tees stretched flat across quilting hoops.

In spin-off folktales, Putty learns to love herself by loving others made of putty, who in turn love her back. Many interpret these postscripts as lessons in agency. Whatever is whispered into you as you are given life is not the final word on who you will become. For their art portfolio, Biju took a series of photographs of the hand-stoned bodysuit. There were never any people in the shots, though sometimes one friend or another would help with staging. The suit was posed draped across empty park benches, captured midair on playground swings. Spread out on the frigid back seat of another friend’s beater, the bodysuit split the early afternoon sun into shards, fractured bird poop shadows against quilted leather. At the end zone of the football field, Biju arranged the body suit so it looked like a long, shimmering snake. Each photo was titled the same imperative: “See Me.”

Emi Noguchi has a shiny new MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Arizona. She is writing a novel about magical illnesses, diasporic healing, friendship, and a mysterious puppet theatre. She will always be from New Jersey. Tweets at @emiafield.