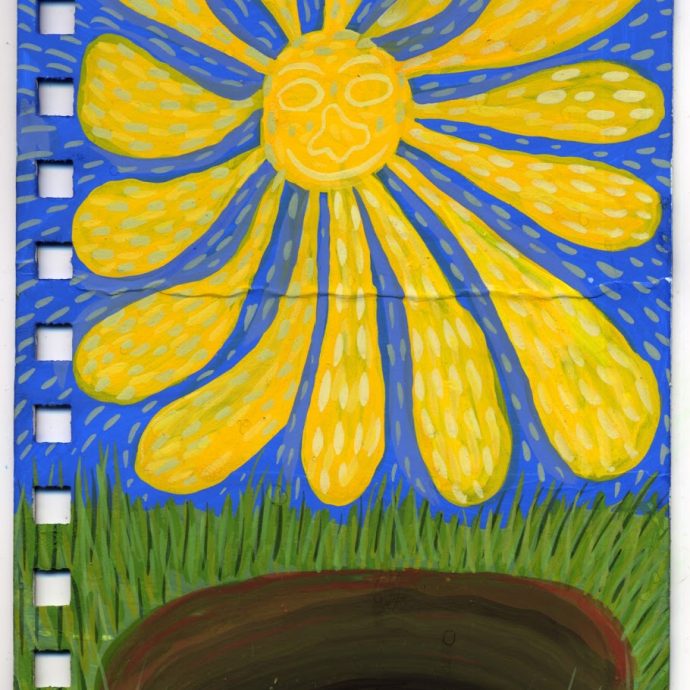

Radish was born of the earth, plucked from the soil by the tufts of her leafy hair. For the first week of her life, she lived in a sunny patch on the kitchen windowsill, pale feet sucking water from an extra dog bowl while the mutt whimpered at her from the floor.

Reporters gathered at the farmhouse. “Why’d you do it?” they asked the farmer.

“I always wanted a daughter,” she replied. “Only I couldn’t find a man decent enough to make one with.”

“What’s she like?”

“Strong and smart.” She smirked and smoothed her flyaway bangs with a palm. “Just like her mother.”

She led them to the kitchen for the photo shoot. Radish straightened in her water dish. She was six days old, but already she knew how to bask in the flash of the cameras, this invigorating new sunlight that fed a different kind of hunger.

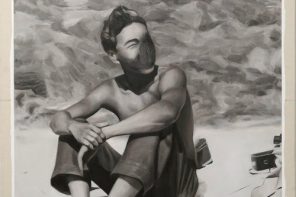

The farmer had a human son named Micah, a beefy, sunburned nine-year-old who yanked Radish’s hair and pinched her rubbery red skin, who threatened to place her on the cutting board and chop her up with potatoes for soup. But if the neighbor children came after Radish, and they did, chucking cutlery at her as she strolled down the farmhouse’s gravel drive, Micah would throw himself at the assailants, kicking and biting. “That is my little sister!” he screamed after their retreating backs, by which he meant: She’s mine to bully.

Soon there were others. Parsnip, who hopped on the tips of her beige toes. Ginger, who squeezed the knobs of her body. Beet with her wet red grin. They were in awe of Radish, who’d come before them and knew the workings of this strange world with its machines that blinked light, gobbled dishes, and spat water into the waiting fields.

With each new birth, the reporters converged on the house in larger numbers. Radish scoffed at how her sisters fluttered their twiggy arms before the cameras and contorted their faces into manic toothless smiles. They had no dignity. No ambition. They trailed the farmer around the house and land, a trio of adoring disciples. “Muck out the barn,” she barked, and Radish’s sisters skipped to that musky building where flies rose from manure in dark spirals. “Mend that broken fence,” she said, and their lumpy fingers went joyfully to work.

Radish refused to help brace the farm for the first frost. She was making plans for escape. A TV executive with a silver ponytail sent a car to bring her to the city.

“The show is called Uprooted,” she explained in his office, which was tucked high and secret as a bird’s nest in the building’s upper reaches. “Every episode I explore a different part of a city. Shopping malls in Tokyo. Parisian restaurants. Vegas casinos.”

The TV executive wore cowboy boots. He clapped when Radish finished her pitch. He loved it. Uprooted could have a little bit of everything: comedy, drama, romance, adventure.

The problem was he wanted to include Radish’s sisters.

“One of you alone is a freak show,” said the TV executive, leaning back in his chair and propping up his boots on the desk. “But put four freaks together? Now that’s TV.”

Word got out that the farmer had used pesticides in her daughters’ making. A chanting group appeared at the edge of the drive with cardboard signs: KEEP OUR DAUGHTERS ORGANIC and GOD HATES GENETICALLY MODIFIED GIRLS.

The TV executive moved on with a new show about conjoined twins. Radish fell into a depression. Her skin paled from red to rose to gray. Her hair drooped and browned. Her sisters encouraged her to join them as they rode the dog around the front porch. The farmer told Radish to stop moping and help gather firewood. Only Micah slouched through the house, bowed under his own dark burden.

“Mom doesn’t want me anymore,” he told Radish. “She has daughters now. She doesn’t need me.”

He held out his arms for a hug. His lips were like fat pink slugs. Mucus dribbled from his nose and dripped off the end of his chin. He was the ugliest thing she’d ever seen.

Radish found herself in the farmer’s vegetable patch. She hadn’t visited the place since she’d been born in early summer. Now a chilly breeze whispered through the stems in their raised beds. Radish longed for the city, the warmth pouring from buildings and bodies; then she remembered how that damp heat had called to mind the steaming fug of a human mouth.

She climbed into the nearest bed. She listened, willing a communion with these inert cousins, straining to hear the susurrations of their breath. She didn’t know how the farmer nudged dumb shrubs into sentience, but it struck her now as a harsh thing, like kicking a snoozing dog awake. A half moon appeared over the farmhouse’s roof. The back door creaked open: Micah, pajama pants tucked into rain boots, a shovel clenched in his fists. He was all shadow as he loomed over the quivering plants. Radish, unseen, was camouflaged inside the leaves, but she could imagine the crazed mask spreading across his face as he raised the blade.

The breeze blew. The smell of the dirt made Radish feel safe but alone, like she was the only living thing on earth. Micah lowered the shovel slowly. With a muted sob, he threw it aside and fled.

She was still in the vegetable patch when the farmer emerged at dawn to start the day’s chores, Parsnip, Ginger, and Beet bumping along behind her as if drawn on a string.

“About time you got to work,” said the farmer as Radish struggled from the bed.

“What is there to do?” asked Radish wearily. Around her, her sisters fanned out across the yard, hobbling with a stiffness she could feel tightening inside her own limbs. For the first time, she understood how hard the winter would be on all of them.

Tessa Yang teaches creative writing at Earlham College. Her fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Cream City Review, The Carolina Quarterly, PRISM International, and elsewhere. Find her online at www.tessayang.com, or on Twitter @ThePtessadactyl.