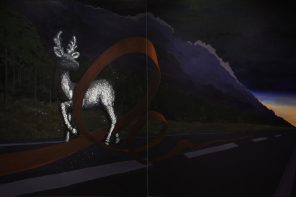

An inverted, roughly triangular reflection projected into the darkness a few feet outside the bus window. The reflection resembled a diagram of the female reproductive system. In the hollow of its uterus flickered a landscape of dark trees against sky.

She thought to reach her hand through the glass of the window and into the suspended reflection. Her elbow encased in the shatterproof glass of the bus, her wrist braceleted by the floating triangle of light, and her hand reaching for the mass of trees that grew thickly along the side of the road.

She thought of children, of having been a child, and in the darkness outside the bus window,

she could see the two children lining up, hand in hand on the side of the road, watching the passage of the bus. She had not seen the children before because the glass of the bus window was opaque. At least, she could not be sure it was transparent. The image of the dark trees visible on the glass did not confirm the physicality of the dark trees visible through the glass. There was no looking through the glass. She had to see for herself; she had to ask the bus driver to pull over, and she had to step down into the darkness outside and look for the children. And by then, the children would be gone.

Dogs barked in the night and when she looked out the window she saw in the reflection that

her mouth was wide open. As if the sound were coming from her own throat.

The bus passed through a small town. Stadium lights lit up a high school football field and

distant sounds reached the bus from all directions. The truncated swells of cheering, the hard r’s and d’s of the announcer’s voice over the loudspeaker.

The sublimation of bodies, she thought.

She imagined the town’s people absorbed into the night. Bodies of fluorescent light. Bodies of sound. The bus rolled down a lantern-lined street, and the lanterns multiplied in the reflections of the bus windows. The glass of the windows glowed red.

This town is a good place, she thought, her hands resting on her stomach, looking out the window. Looking at the sidewalks washed in light, at the closed bakeries, the linen shop, the pointy white church. Tree cones were strewn on the ground and conifers invisible against the black sky.

When she awoke, the bus had left town. It was dark again. The other passengers on the bus

were amalgamated forms of body, seat, and bag. She could not see their faces. She might touch one of them, she thought, on the arm or the shoulder.

She took a closer look at the passenger nearest her, seated across the aisle. A distended body. Pale. A single ear, grotesquely small, was visible in a slant of light coming through the window.

Moonlight, she thought. The ear seemed to smile at her. She touched her hand to her mouth. She felt sick.

In her dream, the bodies of the other passengers were piled around her. Limp, but still

lukewarm. She felt something gummy between her fingers. Rust coating her tongue. A darkness like a smudge she could not rub from their faces. Their faces round and childish.

The trees grew so densely on either side of the road, it was as if the bus were moving

through a dark tunnel. She thought of the small town the bus had passed, and wondered if it still existed. If it had existed at all. It was hard to imagine a time outside of the trees, outside of the bus. The inverted triangle was barely visible now, the floating uterus outside her window. The trees it reflected were the same black as the trees outside the window. Black overlaid on black. Opaque.

The face in the glass of the window was not her face, she thought. To the extent that it was a face, it was not hers. Eye sockets, nostrils, a cavernous mouth, ear canals. The cavities of the face revolted her. The seepage, the mucous, the gunk, the little papillae budding over the tongue. She tasted bile rising at the back of her throat again. More discharge, she thought. The permeable body.

The tunnel of trees closed tightly around the bus now. The trees faceless. Scraps of vomit glutted the back of her throat. The trees, she thought, she was a pane of glass reflecting the trees. The faces of children. The faces of animals. The trees outside teeming with animals. A pane of glass, she thought. Their soft black bodies, soft black wings. An image, she thought. Soft furry legs. Black animal eyes. If the trees should envelop the bus, she thought, if the bus, having swerved off the road and into a ravine. The animals would smell the blood. The exhaust. Superimposed. The burnt flesh. The vomit. A reflection of an image on glass. The animals would swarm. Their wet eyes. The eyes of children. A window, she thought. She closed her eyes and drifted back to sleep.

In another dream, the children were suspended in the dark trees. The trees growing so close together. The two children overlaid made eight limbs. She waxed a piece of thread through her ears. Dark thread woven from her hair. She sewed the children together, through their soft bellies. She hung them from the trees. Red body, eight pale limbs. The dark stitches in their belly bloated with blood. The body dripping over the road. The blood anointing the bus as it passed underneath.

Sunlight, blunt and white, came through the window. It was a blank, cloudless day. The sky

overlarge. Outside, there were no trees and the road had widened into multiple lanes. It was not the same road.

The bus stopped at a vast, six-way intersection and waited for the light to change. No other vehicles passed through the intersection. She looked out the bus window at the crab grass growing along the road, the broken sidewalks. When the bus began to move again, it passed warehouses, a garage, dead lots with the Private Property sign hanging crooked from a chain-linked fence. She made out the white dome of a water tower far away, rising against the blue sky.

By day, the other passengers on the bus were cheerful. They rummaged through their bags,

laughed, and chatted among themselves.

The friendly atmosphere of the bus disturbed her. She was terrified of being addressed, either by the passenger seated nearest her, the one with the smiling ear, or else by the passengers walking up and down the aisle, fighting blood clots.

Where are you from? she had heard them asking. Where are you getting off?

She turned her face to the bus window and let the monotony of the landscape calm her. The grass, the asphalt, the sky, and the buildings were one color. She felt so hungry she was nauseous. The food advertised on billboards along the road was slick with grease. Blot clot, she thought. The grass, the asphalt, the sky, the buildings. A litany.

The bus pulled into a gas station adjacent from a strip mall. The bus driver spoke into the

corded microphone. The sound produced was garbled, but she made out the words stop and four fifteen. Or four fifty, she could not be sure. She looked at her watch. The bus driver opened the door and left.

The other passengers on the bus shuffled about, zipping and unzipping their bags. Finally, someone headed for the door, and the rest followed. She sat still and closed her eyes. When the last body lumbered past her seat, she stood up and turned around. Felt dizzy. The bus was empty.

If she got off now, she would have to stay in this town. That was the deal she had made with herself when she boarded the bus. When she left her hometown because her boyfriend had left her. She sat down in her seat again and looked out the bus window. There was a fast food chain, a laundromat, a foot spa, and a liquor store. The strip mall was identical to all the others the bus had passed. Gray or white building. Boxy signs with the text faded inside.

She stood and moved into the aisle. Someone came up the steps of the bus. A passenger holding a white box. This is for you, he said, handing her the box. She stepped out of the way, the warmth of the food pressed against her stomach. She could not look at the man’s face, so close to hers. She was afraid she would vomit. Thank you, she said.

Evening fell, and the children came out again. They stood under street lamps, hand in hand, and watched the passage of the bus. Their small faces bathed in the orange sodium light, their eyes fixed on her window.

The bus moved from the edge of one town to the edge of another, and she imagined the

bus route as a line running tangent to the perimeters of the towns. She tried to look for the points of intersection where the bus touched each town’s limit. A parking lot of retired school buses, warehouses with the windows boarded up, pump jacks stagnant in dark fields. The floating triangle outside her window projected these reflections against a landscape of motels and gas stations. The bus route a vector, she thought. No, she thought, a ray. Extending infinitely in one direction.

Soon she began to consider the children as the points of intersection.

Looking closer at the children, she noticed that one was ill. The child’s skin drying out and flattening to the bone. The other child was soft and round. Yet, the two children seemed to be amalgamating into one. They stood so close together they seemed to share three legs. Then they seemed to share only two legs, the sick child slumped against the stronger one.

When they stood apart again, there was one child of flesh and the other child, a reflection.

The child stood under a large, black tree, hands clasped together, watching the passage of the bus. The bus passed the same tree again and again and the same child stood under it each time, in the same pose.

The bus had entered a mirror, she thought, a mirror facing another mirror so the same tree and the same child would repeat itself in the same landscape. A reflection of a reflection of a reflection into the vanishing point.

If the bus were to slant and fold into itself, she thought. If all the windows of the bus aligned.

She half-stood in her seat and looked over the bus driver’s shoulder into the open road. She could not see it, where the road would disappear. The headlights of the bus reached only a few feet into the darkness. She sat down again.

The hum of the bus engine filled the small compartment. She kneeled before the metal-

rimmed toilet at the back of the bus and heaved up the food the passenger had gifted her. The vomit was thick and tinged with red. Was an oral abortion possible? she thought. Oral miscarriage, she thought, spontaneous abortion.

She waited for another wave of nausea to seize her body. She would get off at the next stop, she thought. She would get off wherever, she didn’t care. The bile rose again at the back of her throat, but nothing came out. Cavities of the face, she thought. Leaky bodies. Two bodies joined into one with eight limbs. A fetus absorbing its dead twin. She heaved again, and this time the two children came out.

Dogs bark at ghosts, she had heard the other passengers say, as she groped her way down the aisle of the bus. Someone helped her down the steps at the door, and into the dark outside. The bus driver had pulled over in front of a gravel driveway. A vale sloped down from one side of the road, and a cage of dogs was at the bottom of it. The source of the barking. She looked up at the bus and saw the faces of the other passengers pressed against the windows.

The passenger who helped her down the steps led her to a streetlamp and she saw that the passenger’s face was wet, at the corners of the eyes and the corners of the mouth. She wondered if this was the same passenger who had brought her the food. The passenger smiled, revealing slick, fleshy gums, and she bent over the curb and retched.

The dogs barked madly and louder now. She heard the sound of bodies thrown against metal. She rested her hand against her abdomen and sighed. She had to look for the children, she thought.

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint is the author of the novel The End of Peril, the End of Enmity, the End of Strife, a Haven (Noemi Press 2018). Her short stories have appeared in Black Warrior Review, TriQuarterly, and Kenyon Review Online, among others, and have been translated into Burmese and Lithuanian. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate in creative writing at the University of Denver, and the Reviews, Interviews & Translations editor of the Denver Quarterly. thiriimyokyawmyint.com