I don’t believe in god, but I like asking him for favors.

/

Andrew tells me about a room that is never locked. It’s in the back of Saint Michael’s Parish, and though it’s not staffed there is always someone inside. Once he ended up there in the middle of the night. When he knocked a weeping man opened the door. “To pray?” he asked. Andrew nodded. The man let him inside.

/

Around the year 1170, Christina the Astonishing woke up at her own funeral. She’d been dead for three days. When she floated to the ceiling of the church, the grieving people were amazed. They asked her to come down and tell them about heaven. She refused, claiming that she had seen the stinking sins of the living and she could not stand their smell.

/

Andrew sends me a book in the mail: The Sermon on the Mount. From the Bible, I learn that miracles are more common at high altitudes. In an airplane, I’m at once displaced and holy.

/

When I was seventeen my mother gave me a book by Caroline Myss that says that before we are born, we make contracts with everyone we will meet in our lives on earth. This was my mother’s way of saying she chose me. I loved this book because I had spent my entire life up to that point trying to determine what I did to deserve what had happened to me.

/

I talk to god at night because I’m terrified of the dark, and the conversation is a useful distraction.

/

Andrew teaches me how to give things to god. I am to speak them aloud and say, “Please, I can’t carry this anymore.” I have done this only once. Afterward I felt euphoric, like I was floating.

/

In high school, I dated an organ player. He was Catholic, so we argued a lot, but I liked the black print on his forehead the morning after Ash Wednesday, and his eyes, and the way he talked about pulling out all the stops to feel the quivering of six hundred two-story pipes rattling the church windows, the vibrations which become music which becomes god.

/

A friend tells me about the pamphlets that missionaries leave in the laundry room of his apartment complex. They are primarily about paradise, which looks like tastefully dressed women and children with violins in a garden, an orchestra trailing behind them disappearing into the light.

/

I was baptized Catholic, but my brother and I did not go to church. My mother believes in New Age theories about energy and light and my father doesn’t think god is real. My grandmother likes to tell me stories about decades ago, when my father was an altar boy. He attended Catholic school and lit dozens of musky candles. By sixteen, he was setting off fireworks on the church steps and waiting for someone to catch him. Nobody told me what happened in between.

/

When my grandmother asked my brother and me which of her belongings we wanted after she died, my brother asked for her rosary.

/

Two years ago, I read Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love. In it, god appears as a series of images in a fever dream which plagues Julian for days. One year ago, in the middle of winter, I had a dream that I walked slowly through my step-father’s house, touching each object with two fingers. Every item, every person, was exactly where I’d left them.

/

I don’t believe in god, but I’m afraid to get my palm read because I can’t dismiss the possibility that my fate has been built into my skin.

/

Feminist theologian Sallie McFague says that in our new world of nuclear bombs and melting ice, god must become a mother to us, a lover, her body the world. I have been told, too, that god’s body is bread, and that this simple thing can be a miracle.

/

Writer Fanny Howe is Catholic. She wrote an essay called “Bewilderment” on the philosophy of uncertainty in literature, in which a poet argues with herself, and characters leave a story as unsure and full of doubt as they entered it. This is a philosophy against genre, and grammar, and narrative. It is a philosophy of floating. She writes: “There is literally no way to express actions occurring simultaneously. If I, for instance, want to tell you that a man I loved, who died, said he loved me on a curbstone in the snow, but this occurred in time after he died, and before he died, and will occur again in the future, I can’t say it grammatically.”

/

When I was eighteen I started reading Jewish mysticism, though I didn’t know any Jewish people. I liked it because it was a religion built on questioning. I saw the entire faith as proof of a theory I already had: that two people could read the same book, and where one found answers another would find only questions.

/

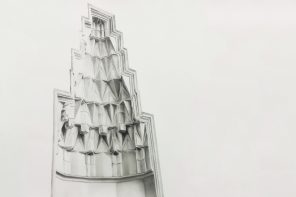

There are two kinds of labyrinths: a maze and meander. The function of a maze is to get lost and find your way out again. In this kind of labyrinth, there are many dead-ends. In a meander, there is only one circuitous route from start to finish. The traveler must keep walking, despite their doubts about the path’s efficiency. In Medieval churches, walking the labyrinth was an act of devotion akin to a long pilgrimage.

/

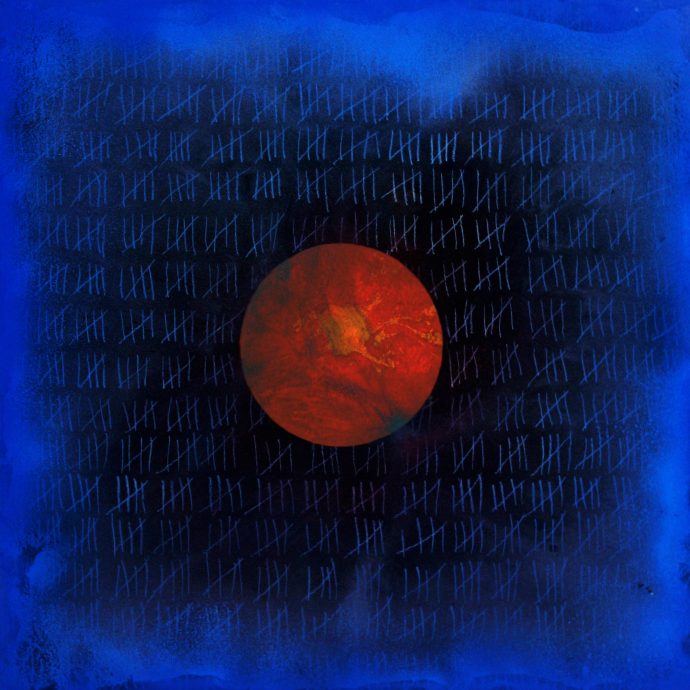

I do not think art is god, but I think it can look like religion. On my desk: a piece of driftwood shaped like a boomerang, a photo of my father fishing, and a box that Andrew gave me, the size of my palm, with a stone and ticket stub inside.

/

I don’t believe in god, but I have opened a door to find two trapped monarch butterflies, moving in wide circles around each other.

/

I don’t have a name for it, but I know the feel of it. I don’t believe, or I’m not up high enough. From where I stand the facts look like this: there is a room with a door that is open. The room is made for prayer. Prayer is a room occupied by the body. Inside, some things are certain; for example, the promise in the shape of a kneeling figure, or the space between two knitted hands.

Rebecca Valley is a poet and editor from Saint Albans, Vermont. Her work has been featured in Black Warrior Review, Rattle, and The Boiler, among other journals. Her first chapbook, The Bird Eaters (2017), was published by dancing girl press. She serves as the editor-in-chief of Drizzle Review and associate poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. You can find more of her work at rebeccavalley.com.