I met with Cole Swensen, the visiting Hurst Professor in Poetry at Washington University-St. Louis, last October. We sat in the kitchen of the Hurst apartment and spoke at length about her recent book, Landscapes on a Train, as well as her upcoming collection, On Walking On. Here, Swensen and I discuss the relationship between her practice of walking and her practice of poetry, the rhythm of writing, and the intrinsic beauty of facts.

Cole Swensen is the author of several books of poetry, including recent titles such as On Walking On (Nightboat Books), Landscapes on a Train (Nightboat Books), and Gravesend (University of California Press). Swensen’s book Goest (Alice James Books) was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2004, and she currently teaches in the Literary Arts program at Brown University.

Aaron LoPatin: At your reading, you mentioned your tendency to dive head first into an obsession, whether it’s ghosts or walking. Do they tend to fade once the book is complete? Do you ever find yourself wanting to revisit or rework a former obsession?

Cole Swensen: Yes, all the time. And though I call them obsessions, they’re simply deep interests. Every time I finish a project, I hate having to leave it. I was going to say that that’s true of some more than others, but I don’t think that’s actually right. Some things feel more done, but Gravesend, for instance, I could have kept writing forever. And the most recent book, Landscapes on a Train, I also would have loved to keep working on. They were both just so engaging, but then a moment comes when I think I want to make it into a book; I want to sculpt a piece of art out of this. And so, in a sense, I have to artificially curtail my interest, but then something else always comes up, and it’s always engaging to get into that new thing. That said, I sometimes wonder how new my subsequent interests actually are, in that everything that I do revolves around landscapes, parks, greenery, paintings (usually landscape genre), walking (which is really just another aspect of the landscape and the park business), etc. They all have to do with how humans look out upon the world and the exchange between the human body and the world body. And I often return to certain projects. I just try to leave many years between so that people don’t remember that I actually have already written a book about a park, for instance. In fact, I wrote a book called Park that was published in 1991, and then I did another one on the parks of Andre Le Notre called Ours that came out in 2008, but I felt that there was enough time in between the two to guarantee a very different approach.

AL: Your last two books have both been very motion-oriented. What about motion do you find poetic? How do you find yourself moving through a poem?

CS: As a reader, and as a writer as well, I’m propelled by rhythm. I’m attracted to poems that have a strong rhythmic base and incorporate long rhythms. Not necessarily long lines, not Walt Whitmanesque, but more a rolling gait, which I use to try to give the writing an effective momentum. Landscapes on a Train offered an interesting variation, in a way, because it’s not the writing body that’s moving; instead, one has the sense (or at least I had the sense) that it’s the world that’s moving. For the most part, the poems were written on high speed trains, and so the landscape was changing relatively quickly. It seemed like the objects at times overlapped, creating a kind of rhythmic counterpoint.

AL: There’s such a unique musicality in that book. How do you navigate between the seeming silence of landscape and the music of poetry?

CS: Is a landscape really silent? When you’re behind a train window, the landscape outside seems silent, with the dimension of sound belonging to the inside, in that there are sounds all around you in the train, so the sound-scape and the sight-scape don’t match, which can result in some interesting contrasts. On the other hand, as John Cage famously underscored in so much of his work, sound is always present. Outside spaces are full of sounds—birds, insects, wind, rain, streams, etc. In working on the Train project, I was aware of a kind of synesthesia in which the inability to hear the outside slid the realm of sound-relationships onto visual elements, creating “rhymes,” for instance, rhyming colors or rhyming forms: to see a conical tree and then a steeple creates a rhyme of forms that then turns into a sound rhyme or informs the sound relationships in the poem. Or perhaps the line of a road next to the line of a stream creates a parallelism that ends up echoed in the writing. It’s not a matter of thinking about such things consciously and then reproducing them; rather, just being open to and interested in grammatical and syntactical structures in the landscape seems to let them emerge in the poetry.

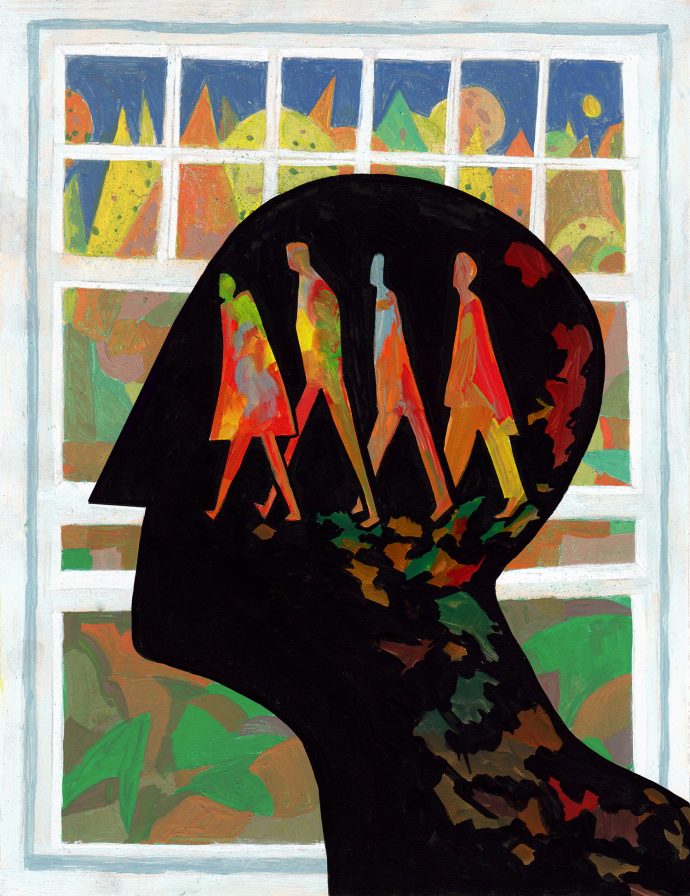

AL: In your book The Glass Age you write: “So often in Bonnard’s work the window is where we actually live, a vivid liminality poised on the sill, propped against the frame.” In Landscapes on a Train, the speaker is quite literally propped against the frame. How does that separation affect the subject of the poems?

CS: Windows are important to me both actually and symbolically, and they play an important role in both books. They function not only as a constant element of transparency and a constant play between outside and inside, a constant questioning of the distinction, but also as a constant framing device, underscoring framing as an inescapable fact, no matter what the situation. Bonnard’s work is particularly active in this way in that we’re often made very aware of the frame of the window, thus of what is being excluded. That said, the two books use the window very differently. In Landscapes on a Train, the window functions as constant mediation, and, oddly, joins rather than separates. It allows for a fusion with, an immersion in the landscape, whereas in The Glass Age, I was engaged not only with questions of framing but also with the materiality of the window, with the history and manufacture of its material, and with the ways that its materiality conditions our seeing both literally and figuratively.

And yet despite the inherently transparent nature of a window, Bonnard’s window paintings—like most of his work—use deeply saturated colors. He creates the window as an opaque object. We cannot see its clarity. The window becomes a painting in itself, and he, too, uses the window not as a barrier but as a mode of passage. For instance, in the foreground, in the room, he frequently incorporates a variety of patterns—on the tablecloth, on the wallpaper, etc.—and then will use related patterns and at the same scale and degree of detail in the foliage outside. It creates a fusion/confusion between inner and outer worlds that invites a similar fusion of inner perspective and reflection and outer world. The window becomes a mode of being-in-the-world, making it possible to live from the outer boundaries of the body outward. It’s a way of living beyond the body.

AL: Moving on to your upcoming book: you described your walking as a practice. What influenced your views on walking as a practice? How long were you walking before you decided to write about it?

CS: I’ve always loved walking, and I’ve always used it simply as transportation. I never thought about it as a particular thing—activity, practice, etc.—until, as a young adult I became aware of Thoreau’s essay “Walking,” and then of walking meditation, and other formal approaches to the activity. I usually walk a few miles a day, and I’m using simply going somewhere, but I do at times play with it quite consciously, orchestrating and manipulating the walk, and it’s those walks that have come to feel like a practice of sorts. One way I might do this is by deciding on the kind of attention that I’m going to apply. So, for instance, Have no internal thoughts, but name to yourself everything you see (which is, of course, impossible), or List everything good, warm, positive, and/or promising that you pass; on this sort of walk, I consciously decide on the mental state that I’m going to adopt. I can’t always keep it, but adopting it makes me aware of my mental state—and my mental state as a conditioning element—in a much sharper way. A variation on that is to consciously choose an address or an approach to the others out walking, such as Imagine where everyone you pass has just come from or Put a name to the mood you see expressed by each face that you pass. I adopt this sort of approach when I’m using walking as transportation; on the other hand, when I’m “just out for a walk,” very different sort of directives can come into play, many of which are similar to poetic constraints. One that I use a lot—and that’s going to be increasingly pertinent in the upcoming years, I fear—is Turn left whenever you hit an obstacle. It’s really interesting to see where you end up. On such a walk, I’m usually leaving from the door of our apartment building, so the first obstacle I hit is always the building across the street. The first several moves are, similarly, usually the same, but then I’ll hit a light that, depending on whether it’s red or green, sends me a different way, and it feathers out from there. I sometimes use an alphabetical variation on this theme—starting with A (or Z, if you’re feeling inclined), walk straight ahead until you see a word on a sign that begins with the letter, then turn—either direction, but you must turn; if you can’t turn left or right, you must turn around. Constraint-based itineraries get you to places outside of your activity-based, contingency-based territories.

AL: It seems like an inherently spiritual practice. From my understanding, there are two different types of sacred walking: on one hand you have the overly mindful — walking for walking’s sake — and on the other is the pilgrimage. Where do you feel like you fall on this spectrum? Do you ever feel like a pilgrim?

CS: I don’t think of walking, even though I talk about mental states related to it, at all as a practice in the spiritual sense, and I don’t think of myself as a pilgrim, though I would love—from an entirely historical perspective—to do some of the traditional pilgrimages. There’s one for instance, the Cammino di Francesco, connected to the life of Saint Francis of Assisi, that follows an old Roman road from Florence to Rome—I’d love to do that some day. Another is the Shikoku Pilgrimage, which takes in 88 Buddhist temples on the Japanese island of Shikoku—that would be marvelous to do. I’m attracted to pilgrimage in its broadest sense because I see it as inherently connected to community and as a community-building gesture. Every pilgrimage is by definition engaged with an intentionality shared by a great number of people, and over a great expanse of time. The time element is crucial in that it underscores the pilgrimage as a practice that simultaneously spans both time and space. So again, not necessarily the spirituality, but the sharing of a cultural custom, as well as simply the thought that literally millions and millions of people have done this very same route, have over centuries put their feet in these same places.

AL: Do you feel as though you had any teachers or masters for your walking practice? Who are your favorite famous walkers?

CS: I think immediately of Richard Long, the British artist who set walking as his art form. Hamish Fulton is another whose art form is walking. In both cases, they refuse the ephemerality of the walk, which is perhaps simply because you can’t build an art career on something that utterly disappears as it’s being created. So both of them use photography as well as other visual practices, such as drawing and mapping. Hamish Fulton photographs places he’s been and Richard Long creates things such as, in particular, lines or circles in stone, and then photographs them. The first one that Long did is a line walked through grass, so it conveys the idea that a walk makes a trace, and he makes that trace permanent. As I understand it, each considers that the art is the walking itself and not either the trace or the photograph. I find that a really interesting idea — of constantly slipping the site at which the art is taking place, so that what you end up with is not the walk, not the line, but the photograph. I’ve always valued his work, and Fulton’s, for the idea of taking a walk and making it constantly open out into other forms. You could say that about writers who walk, too. They take walks, which are ephemeral, and change their temporal dimension by writing about them. Another walking hero for me would be John Muir. What a great attention he had, a sense of being, based on the idea that a naturalist has to occupy the space.

AL: In your poem “Gerard de Nerval” you write: “In mid-nineteenth-century France, there was a distinct turn in the literature of walking from the countryside to the city.” As you shift from a pastoral experience in Landscapes on a Train to a more urban one in On Walking On, how do you feel like your voice changes as you occupy these different spaces?

CS: The tones of the books are very different, but I don’t think it’s the rural versus the urban. Most of my walking is urban because I spend most of my time in cities, but I also walk a lot in rural areas, and the experiences are, oddly, largely the same in many ways. I would attribute the differences in the tones of the books more to speed. For instance, Landscapes on a Train seems to have a very linear momentum that comes from the speed of a TGV. The lines are long and echo the head-long passage of the landscape, whereas in On Walking On, the lines are much shorter and the rhythms are much tighter. I’ve always thought that the rhythm of the foot has a lot to do with why so many writers love walking. It’s a bodily rhythm that echoes the rhythm of handwriting and of typing.

AL: What about the rhythm of research? I feel like there’s a different type of research going into On Walking On.

CS: Yes, and that of course is the rhythm of reading. Often my major “research tool” is reading. In the book Ours, the book on Andre Le Notre, I was going to his parks, but I was also doing research on the development of garden design and other things around that, which was taking me to libraries and to archives. In On Walking On, all I did was go to other people’s books, which I could go to anywhere, and in fact, I did most of the reading in public parks. The rhythm of reading always seems to me to be a very smooth and slow one, and much more homogeneous than the rhythm of walking. Walking is staccato. You’re constantly on the outside, constantly exteriorizing, accompanied by slight and regular jolts—not at all unpleasant, but not smooth. You’re constantly aware of the outside of your body, whereas when reading we tend to go immediately to the mind of the book, which is obviously our own minds as well.

AL: I’ve heard you describe your research process as “mining for information.” As technology progresses, have you noticed any differences in how you access that information?

CS: I use the internet more and more—and largely because there’s so much more information available on it every year. I love the expression of the internet as a “rabbit hole.” I’m working, at the moment, on a series on visual artists, and what I can find out on the internet is just amazing. And then, suddenly nothing—you hit on someone who is very interesting to you, but apparently not enough to anyone else to be featured online. I’m fascinated by those internet gaps. I’m doing something on the Cone sisters at the moment, Etta and Claribel Cone, who were collectors in Baltimore. They’re best known for their collection in the Baltimore Art Museum, but they also traveled widely, were good friends of Gertrude Stein, and led very adventurous lives. They have a fabulous collection of lace. The piece I’m working on is about the arc of a lace fan as an architectural element, and lace itself as architecture, and there’s nothing on the entire internet about these people. I could find only one image, so for that one I can’t do the research until I can actually go to Baltimore—and there’s something about that, too, that I really like; I like projects that make me get up and go somewhere.

AL: What is the beauty of a fact? How do you balance fact with form in your poetry?

CS: What a great question! Because to me, facts are beautiful—some more than others, of course, but the fact of facts I find in itself beautiful. There’s a great book sitting in my kitchen, and I read it all the time: 1,227 Quite Interesting Facts to Blow Your Socks Off. And they’re just amazing. The beauty of facts to me is that they are distilled. That sounds so simplistic, but they have a clarity, like exceptionally clear water. For instance, an octopus has three hearts, and that’s a fact. There’s something just so lovely about that. And, obviously, it’s lovely because of all the associative and symbolic meanings around the heart—if it were three livers we’d be much less impressed. (It also has nine brains, but no one ever seems to mention that . . .). It’s the way that a fact, while having a literality, also radiates and gets tangled up in our symbolic and metaphoric associations. A fact is never containable. It’s always overflowing, going elsewhere, collaborating with our imaginations and yet remaining a fact.

AL: Yes, and I recall another interview in which you talked about poetry’s “ethical edge”—how you were trying to establish an ethic to your work without being didactic. Do you feel like facts play into that ethic?

CS: They absolutely do—and again, it’s related to clarity. I’m interested in the ethics of daily life, the ethics of incidental things, small things, those inherent in our most mundane actions, and facts seem to hold a capacity for sincerity (both as disinterestedness and in Creeley’s sense of being rooted in the gut), clarity, and accuracy, all quite modestly. It seems to me that those are three poles that play into an ethical stance or approach to a subject.

AL: In your research did you come across any fun facts about walking, any cultural distinctions or attitudes towards walking that stand out?

CS: Though it’s not a cultural distinction, per se, one distinction that really stood out to me is that between “internal” and “external” walkers. The internal walkers—and Rousseau offers a pronounced example—walk to think; their focus is inward. In his Reveries, he rarely talks about what is right in front of him or what he’s passing through, but instead uses the occasion to mull over other events in his life. An example external walker, on the other hand, might be George Sand. Her attention seems always rooted in what’s directly before her; her consciousness feels largely externalized. Of course, most people are a combination of the two, and what one writes about a walk later is not necessarily what one experienced while actually walking, but I found the distinction useful in thinking about how this most basic human activity is exercised very differently and for different purposes by different people.

AL: This last question is a silly one: For as long as I can remember I’ve had this quote in the back of my head. I had always attributed it to Paul Valery but further research actually ties it to the English poet John Wain. It goes “poetry is to prose as dancing is to walking.” As both a poet and a walker, how do you feel about that quote?

CS: I know it too—it’s playful, but it falls into the trap that all analogies do—one thing simply is not and never can be another, and metaphor and analogy do great violence to the things of the world in denying them their sovereignty and integrity. So I think of it as a false analogy, though a very clever one. But for me, it’s false because, one, I love all four of those things and would not ever put them in a hierarchical order or in any other way compare them to each other. That quote seems to imply that prose is less interesting than poetry, and walking is less interesting than dancing—for me that’s not true.

AL: I feel like it plays along with people’s resistance to facts in poetry.

CS: Yes, I think you’re right—people expect prose to be factual and poetry to be somehow opposite—whatever that might be—when, in a sense, poetry is much more factual because it is its own fact—it’s not reporting facts about the “outside” world, which could be said to be true or false, but is instead constituting its own world, of which it is the fact and necessarily true.

Aaron LoPatin is a poet who lives in St. Louis.