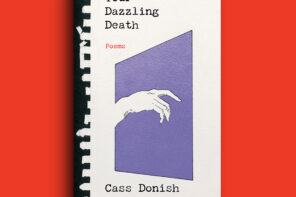

Cass Donish is a queer poet, writer, and educator from Greater Los Angeles. They earned an MFA from Washington University in St. Louis, where they co-founded The Spectacle alongside their late partner, the poet Kelly Caldwell. Donish’s third poetry collection, Your Dazzling Death (Knopf, 2024), is an exploration of grief, queer love, and young widowhood. The first week of March, 2025, marked a decade since the very first time Cass and Kelly met, as well as The Spectacle’s beginning; late March marks the five-year anniversary of Kelly’s passing. Below, Donish discusses their collection, the experience of writing through loss, and the early moments that became the magazine.

Jeron Hicks (they/them) is a poet from Rolla, Missouri, concerned with the conjunction of gender identity, rural social landscapes, and political modification. They have two cats named Ducky and Miss Pearl, a lizard named Zeppelin, and a somewhat strange passion for Pokemon.

Kelly Caldwell’s posthumous debut, Letters to Forget (Knopf, 2024), is now widely available.

Jeron Hicks: Thanks so much for taking the time, Cass. I had the privilege of reading your recent book, Your Dazzling Death. The text keeps a pearl of hope within its tremendous grief; could you tell me more about your book and its relationship with loss?

Cass Donish: Thank you, Jeron. The collection revolves around the loss of my partner, Kelly, to suicide in 2020 after a harrowing year with treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: episodes, hospitalizations, various medical interventions. For months after her death, I was at risk of slipping out of the world. This extraordinary person, my lover, was suddenly gone. Instinctively, I began doing dozens of tiny tasks that I later articulated as “casting spells on myself,” to keep myself here, to tie me to the world, to remind myself that I had a body, that I had hands and feet. To tell myself I wasn’t dead. Each day was organized by impulsive rituals. I walked between two and seven miles a day, arranged flowers and rocks, took photos of my arrangements, made and remade a sizeable altar, put photos of my lover in every room. I spoke to her, to my father who had died twelve years earlier, to other ancestors. I got memorial tattoos. I had a memorial tree planted. I ordered an artisanal ring, made with her ashes and my own period blood. I took grief tinctures sent to me by friends. I made peppermint tea with mugwort, to try to dream about her. I lit a dozen candles every night, for an entire year. And I wrote. At first, I didn’t think that I was writing. In grief, my writing practice was completely disrupted, almost erased. Still, somehow, fragments appeared in my notebooks, and in documents on my computer. At some point, I was able to start looking at them, shaping them into the poems that eventually became the book.

JH: One remarkable aspect of Your Dazzling Death is its delicate balancing of beauty in a world filled with anguish. I was astonished by how vividly you enact living in a book that so explicitly reveals the impact of loss. What is the role of beauty in this collection?

CD: At a reading, someone asked me why there are so many lush descriptions of landscapes and food in a collection that’s about grief. I realized that I’ve had the urge to create, in language, beautiful things for Kelly, even now that she’s gone. Writing about traumatic loss is difficult, because I don’t want the poems to be traumatic. I want them to offer something counter to trauma, something healing, nourishing even, although I also want them to be real and to portray the complexities and realities of suicide loss. Kelly loved cooking, she was an excellent baker and identified as a home chef, so memories of particular foods and smells I associate with her are powerful for me. There are still some foods I still can’t eat, but I can write about them, especially apple pie, which was Kelly’s favorite. In terms of beauty, I think about its role in elegy—a term that is fascinating to me in the different ways it’s used today. Poets (myself included) often use it to talk about pretty much any poetry of grief, but one scholar told me that my collection is not technically an elegy, in the way she thinks about elegy. Traditionally, an elegy is made up of three parts—lament, praise, and consolation—but more importantly, it’s assumed that the person who has died is not there, not listening. What I mean is that the conversation, the consolation, isn’t for them, but for the living. In many of my poems, Kelly is not gone. I’m still trying to console Kelly herself. To comfort her. It’s common for elegies to include natural elements, the cycle of the seasons, flowers, other things that grow, die, return—again, to console the living. So I think I do all of this in the book, but for Kelly. A poet friend said to me, “If this is an elegy, it’s the most erotic elegy I’ve ever read.” I appreciated this comment because it feels true to me that these poems are love poems. Losing a lover, especially at a young age when not many peers have been through that, is absolutely stupefying. I’ve said before that no one wants to hear a widow talk about how they miss their partner’s ass. But guess what? I want to talk about it!

JH: I keep coming back to “Kelly in Violet,” the book’s centerpiece, which is in conversation with Marosa di Giorgio’s The History of Violets, translated from the Spanish by Jeannine Marie Pitas. Can you talk about how this sequence came into being, and your process of writing with or through another text?

CD: The History of Violets is a short work of strange, haunting prose poems, which I had read and taught a number of times before. One day, the phrase your dazzling death—which is from the first page of di Giorgio’s collection—popped into my head when I was thinking about Kelly. It felt painful and resonant at the same time. That day, almost without thinking, I took the first prose poem in the book, and started writing through it, alongside it, a kind of erasure or translation, or the opposite of erasure, a filling in. Suddenly I fell into the project of writing through the whole text, section by section. I didn’t know where it would lead, I didn’t know if I would ever publish it, I didn’t know what to call what I was doing. It became “Kelly in Violet,” an intertextual sequence about my experience of loss and its aftermath, which ended up forming the middle section of the book. At some point, I realized the word “palimpsest” was the most appropriate for the form. Writing something over something else, with traces peering through, still visible. I wrote my story through di Giorgio’s language, preserving what I borrowed from her in gray font to visually show the process. But her words took on different meanings, such as one section in which language she used to describe mushrooms becomes, in my poem, language about transness. Di Giorgio passed away in 2004, but I contacted Jeannine Marie Pitas, the translator of The History of Violets, and sent my sequence to her. She was so supportive and encouraging, and it’s been a powerful conversation to share with her—about process writing, different kinds of translation, and acts of imagination that take shape in language.

JH: Another poem I return to is “Via Negativa,” especially the tension between abstracts like “not the idea of the lover / or nature” compared to specific imagery like “Roman lavender, / or invasive eucalyptus, its vibrant / takeover.” I’m interested in these scalar shifts throughout the book—from abstract to concrete, from personal to national or global, from human grief to environmental crisis.

CD: The concept of via negativa comes from negative theology, a mode in which the divine can only be defined by describing what it is not. I’m attracted to this kind of reverence, an acceptance of the ineffable. As if we can only glance sidelong at reality; we can only undescribe it. This is how I was thinking about grief. I believe that all griefs touch each other, and that as I was processing Kelly’s death, losing her became inextricably tied to the loss of ecosystems, and to suffering and injustice experienced across different human and nonhuman communities. I was grieving my lover and grieving the world, and the boundaries began to dissolve. Even time began to dissolve. I felt close to death, connected to surges of primal grief. Kelly and I were both reading and writing about climate catastrophe, and it’s something we discussed often, so that was an ongoing conversation with her that continues in the poems. Glaciers melting, species extinction, a suffering planet—all of these became a part of the manuscript, as I was exploring queer and trans love, queer and trans grief. So many of us are carrying individual and collective losses, as communities are marginalized, disenfranchised, incarcerated, killed. People are grieving everywhere, in every room. At my readings, people have shared with me that they recently lost a parent, a sibling, a best friend, a partner. A friend told me that his cat died while he was reading my book, and that the poems helped him. This was a beautiful thing for me to hear, because of how I see all our griefs as interconnected—not all the same, never, but arising from our deep and sacred desire to honor being alive, to honor the dignity of life itself. Our griefs are rivers that flow to the same ocean, interweaving through our entire lifelines. Grief is ongoing. It can’t, it shouldn’t, be otherwise. In this world, we need desperately to be able to grieve. I didn’t write my book to write the grief away. I write toward grief, with grief. I write to make more space for grief, not to moderate, resolve, or reduce it.

JH: Toward the end of the collection, I noticed a shift in momentum, especially in the poems “On Proliferation” and “The Moon Is a Hen with White Feathers,” which also both feature bold text at different points. What spurred this visual modification? What psychological valences were present for you here?

CD: I think of my book as one in which many voices are speaking. I believe that we are not only ourselves, we never speak completely alone. Whether we know it or not, we speak with others—by speaking an inherited language, which our ancestors may or may not have spoken; by reading; by friendships; by influence. We are inside culture, inside systems of representation, not outside of them. In “On Proliferation,” I think of the three bolded lines as a prayer, one that others can join. “By perceiving you, I extend you. / By remembering you, I extend you. / By imagining you, I extend you.” Prayer can be desire, power, imagination. Prayer is often collective. “The Moon Is a Hen with White Feathers” is more of a performance piece. The phrases and lines in bold are meant to be read by a second speaker who joins in unison with the primary speaker, so that two voices are heard. I’ve read this poem at events, with several different readers as the second voice. I mean to say that the process of healing, of creating, of speaking, is communal. Perhaps voices from beyond this world are a part of writing too. Spirits are present.

JH: Could you tell me a few of the other voices or texts that feel present in this book for you, besides The History of Violets?

CD: Brenda Hillman’s Death Tractates, Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho, Gloria Anzaldúa, Rainer Maria Rilke, Mina Loy, Alejandra Pizarnik, Etel Adnan, Victoria Chang’s OBIT, Roland Barthes’s Mourning Diary. To name a few.

JH: Are there any reflections you’d like to offer looking back on ten years since the beginning of The Spectacle? Is there anything you could share with us about those early moments, a decade ago, that became the magazine?

CD: Kelly and I met up at a cafe across from Washington University in St. Louis on March 2, 2015. She was a PhD student in the English Department, and I was doing my MFA. She wanted to start a magazine—she had already given it the name The Spectacle—and I was interested in working on an editorial project. Issue 1 launched that fall. I still remember our first meeting so clearly, how intelligent and animated she was, how bright her eyes were, as we sat across from each other at a small table, surrounded by people. I couldn’t have guessed that a year later we’d be falling in love, coming out as queer together, going through gender transitions together. I couldn’t have guessed that five years later I would be grieving her. The magazine was our baby. It was the beginning of our friendship, our intellectual companionship, and eventually our romance. We ran it together for five years, until her death. After that, I worked on it for another year or two, then stepped away. It’s been amazing to see it survive and thrive, changing into new versions of itself as new editors give it their vision and energy. I think Kelly would be thrilled to see it living on.

JH: What transformations are you undergoing today?

CD: I am always changing. This wasn’t always the case to the same extent that it is today. Loving Kelly changed me, and losing her changed me. I’ve tried to open up to transformation as a way of life. I’m much more willing to let the world change me, to be moved, to open again and again in ways I didn’t know were possible, even if it means—well—that I must continually change my life. After the one-year mark passed, I started going by Cass, dropping the “ie” that used to be at the end of my name. I had wanted to make this change for some time, as a part of my transitioning nonbinary gender. But also, as I continued to metabolize grief, I knew that I was becoming, had become, a different person. My grief, my gender, interwoven in this act of agency, the act of changing my name. I believe that we’re living in a time when we have to figure out how to change in ways that may feel impossible, for our material but also our spiritual survival.

Read excerpts of “Kelly in Violet,” from Your Dazzling Death, here.