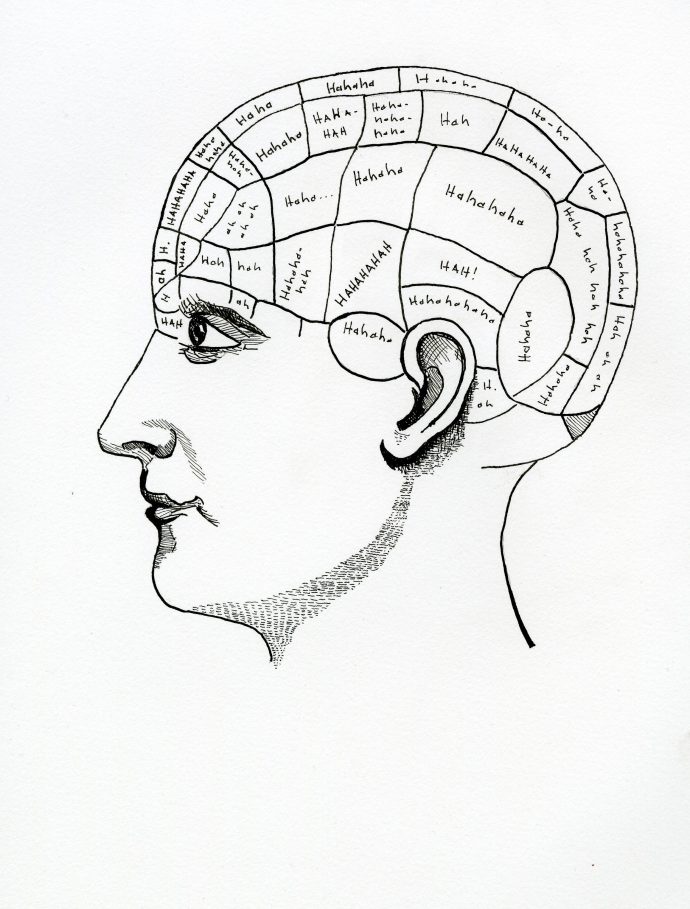

“There is nothing very benevolent about laughter.”

—Henri Bergson, Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1900)

Bad Laugh #1

It’s the summer before my senior year of college, and I’ve moved to an off-campus house of friends of friends, people I don’t know well. One evening or afternoon four of us are sprawled around a giant living room, eating sandwiches. One of my housemates, a first generation American, is telling us about language barriers between her and her parents, how when she was a kid she felt like her dad didn’t like her because he didn’t know how to talk to her. Then she came across a piece of paper where he had been practicing English lettering by writing her name over and over again. As she is remembering this moment and attempting to articulate her complicated feelings about it, she bursts into tears. The other two people in the room also burst into tears, spectacularly, spontaneously, simultaneously.

I start laughing. I break out in big whoops, then jerky, gasping, silent laughter. I cannot breathe. I cannot recover. I cannot stop. My housemates glare. “It’s not funny,” they say in choked voices. “Stop it.”

I am mortified. I’m still laughing.

I now understand this moment as some kind of crossed wire response. My laughter meant to be tears. I was sharing in a moment of collective affective intensity misrouted through the emotional channels available to me. That I could not perform empathy or belonging through such a vulnerable display as crying makes sense, given how unskilled I was at communicating and expressing emotion. But I was feeling with them.

I came across as unfeeling. The laughter that I produced seemed directed against my friend. It seemed cold, mean, wrong: it was bad laughter. It was, in Henri Bergson’s words, a “momentary anesthesia of the heart.”

Laughter is “incompatible with emotion,” Bergson writes in his well-known essay on the subject, published in 1900. In his understanding, laughter depends on social indifference; it requires experiencing reality, and other people, at some remove. Laughter is neither “just” nor “kind-hearted,” he concludes (91). It is quite cruel. Indeed, some of his examples are uncritically, painfully cruel: his analysis of the humor of deformity, for example, and of “the negro” as a comic figure. These examples remind us of laughter’s violence.

Sara Ahmed has written at length on the figure of the feminist killjoy, who “ruins the atmosphere” by, among other things, refusing to laugh at offensive jokes like the ones Bergson takes up as exemplary of comedy. Meanwhile Lauren Berlant is working on humorlessness and “underperformed emotion,” particularly deadpan and other modes of flat affect. These theorists are giving valuable attention to the politics of refusing or resisting laughter.

I want to think about laughter that is the wrong response. I don’t mean “politically incorrect” laughter; I’m not interested in defending oppressive jokes. I mean laughter that is out of sync or context. Laughter that slides into a space that anticipated something else. When you get the joke late. When you get the joke but it’s a different joke: you laugh at a homophobic comment as if it were camp. When there is no joke, but you’re laughing anyway, because something is off or over-intense or uncomfortable; because you’re not prepared, or willing, to be present.

Bad Laugh #4

It’s 2006, and I’m in Philadelphia giving my first reading. I’m reading from the section of my (currently abandoned) novel where my protagonist, a teenager with anorexia, is writing a letter to Sylvia Plath. She pledges to conquer the world after she reaches her ideal weight, and the room responds with a Ha! I smile like I meant it. In truth I am surprised to learn this is funny.

I’ve since started calling that project a comedy, a defense against or apology for what I worry is its very self-seriousness. Paradoxically I’ve also become defensive about, apologetic for, the comedic strategies of my fiction. Much of my work involves perverse logic, grotesque imagery, satire, parody, fan fiction, the flat kitsch of “bad” writing. I worry that by inviting laughter, I’m letting readers off the hook. Like laughing means taking things less seriously.

Bad Laugh #7

Is all laughter bad laughter? A friend recently, subtly, shamed me for calling Trisha Low’s The Compleat Purge funny. The first part of the book is a sequence of suicide notes attributed to an author-entity named Trisha Low. It is a tragicomic work. When I called the project funny, the perception was that I was reducing the tragic dimension. I was not seeing the underlying pain the book expresses; its very real feelings. In fact, I was and do. I also see, and value, Low’s overwrought melodrama, the flippant confessionalism, her (funny!) exposure of the ways in which the threat of suicide can operate as a manipulative demand that one simply be loved harder. As Barbara Kruger has observed: “If you think there’s a long stretch of unoccupied emotion between laughter and sorrow, then think again.” The Compleat Purge performs vulnerability in a vengeful way; it dares us to laugh. If I’m laughing, it’s to show I get the joke. It’s to express I feel you. I’m feeling with you.

Bad Laugh #8

I meet up with a partner while she is watching a friend’s kid. The kid is three or four, I think. My girlfriend has noticed that he laughs whenever she does. She demonstrates. We’re watching the news, sports. Football stats, whatever. The point is it’s nothing funny. She laughs, and the kid looks at her, unsure. He catches her laugh and repeats it. We laugh at him. He laughs back. He’s trying to get the joke. He wants to feel with us.

Megan Milks is the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, winner of the 2015 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Fiction and a Lambda Literary Award finalist, as well as three chapbooks, including The Feels, forthcoming from Black Warrior Review.