I am preparing to write a book about the death of the mother.

To write such a book requires first of all a mother, but a mother of a certain kind—one who does or thinks something remarkable and interesting in a visible, externally apprehensible, or documentable way, or:

a mother whose interior life secretes in its wake a snail’s trail residue of legible, knowable traces, or:

a mother whose incoherent, illegible, and unknowable archive you are invited to investigate, or else creep into at night, verboten.

Or, lacking all these, you simply need a mother who has died.

I want to write a book about the death of the mother. From the outset, I have concerns.

My mother is not famous, accomplished, or the subject of little-known scandal, nor am I famous, accomplished, the subject of little-known scandal. My mother prefers not to speak at all; I also prefer silence, but I especially don’t want to speak for her.

Perhaps, most importantly, my mother is not yet dead.

How can one write a book about the death of the mother before the death of the mother occurs?

And yet, how can this book be written in the after, when there will really be no way to know anymore what it’s like to be alive in the world with a mother, when that life will be completely lost, extractable only through infinitely corruptible recollection, soaked with nostalgia or regret? It is only when you lose your mother that she becomes a myth.

The book of the death of the mother must be written while there is a mother. She who is motherless knows nothing of having a mother and can add nothing pertinent to the book about the death of the mother. Once the mother has died there is no mother to speak of.

This is perhaps a book not about the death of the mother but simply about the mother who will insist on being left alone and remain unknown.

Not so. Death is inscribed in the story of the mother. Part of her mothering is her dying, imperceptibly, during the years of your acquaintance. When she has died, she will have finally fulfilled her destiny as a mother: to leave you motherless so that you can thrive.

Shelves overflow with the books of dead mothers, Barthes, Albert Cohen, Beauvoir, Ernaux, Ben Jelloun, dead mothers crouch and squat, cross and recross their legs, lick their fingers to page sublimely through the tomes about them, with a querying look: Do you want your mother to be dead? No. But in the books it’s always too late, too late to know or to say what the mother is like, too late to ask or to find out what you are like, how much you are like your mother, because everything is illegible when you are groping wild-eyed through the fog of grief. Everything incomprehensible except your own feelings about your mother, but as we all know, nothing obscures a mother so well than your feelings about her.

Every good story starts with a dead mother. Nothing worth doing is possible until she dies. Then at last you can be a hero to yourself. As long as she’s alive, you’re only somebody’s child.

Once many years ago, a friend asked me to drop him off in a remote, rural location, where he was meeting other friends, but when we arrived, the other friends were nowhere to be seen, and I was reluctant to leave him there alone in the middle of nowhere, whereupon he said:

but the moment you leave is when my adventure begins.

That was the day I too became a mother.

Or perhaps I am simply preparing to write the book but can’t yet write it, the book with catastrophe at its origin. The book of testimony, I, its author, the survivor, who will bear witness to the disappearance that has not yet occurred. As long as she’s alive, no catastrophe. Until she disappears, no book, no occurrence, no dream, blank page, no need to say or think the contours of the apparition that is, naturally, ghostly, who appears in a dimly lit corner of the mind, essays one word, a single, uncannily familiar sound, then, thinking better of it, retreats into familiar silence.

It’s been 300 days since I saw my mother.

On the sixty-eighth day since I saw my mother, a friend’s mother dies in a faraway city, before he is able to go see her. There is no possibility of a funeral.

My intention to write about the death of the mother now seems tactless, flippant, offensive, ill-timed, in this grim season of endless death, the perpetually shattering detonation of the death of mothers, so many mothers, but not mine.

No season is apt for the death of the mother. I observe that friends whose mothers have died, no matter how long ago, mention a thing their mothers once wore or ate, a thing their mothers always used to say, and I hear their voices catch slightly in their throats, like the snap of a wrecked wing, one heartbeat before the crash.

I want to make justifications, to say: not that it’s theoretical, but that it’s pre-emptive. Not morbid, but embodied. A plea. Addressed to? Not that I can’t wait for her to die, but that I can’t wait to write it.

And there’s the sense that I will never be able to reconcile motherlessness unless I write toward it now, from my present state of not-motherlessness. From the cowed safety of not-motherlessness I can contemplate the there-not-there mother, who keeps company through absence, whose criticisms will inhabit me, whose imagined attentiveness casts a thin beam of light impossible to extinguish. Her desire to be pleased will not wane. I will try and try, even in the afterward, but I will never. This may keep her bound to me, I’ll have only to be,

her eyes remaining dry to the image of your becoming, she will love yet not-totally-like everything about you, but she reserves judgment and watches you flail, with patience, or impatience, for your sake, for the sake of your survival.

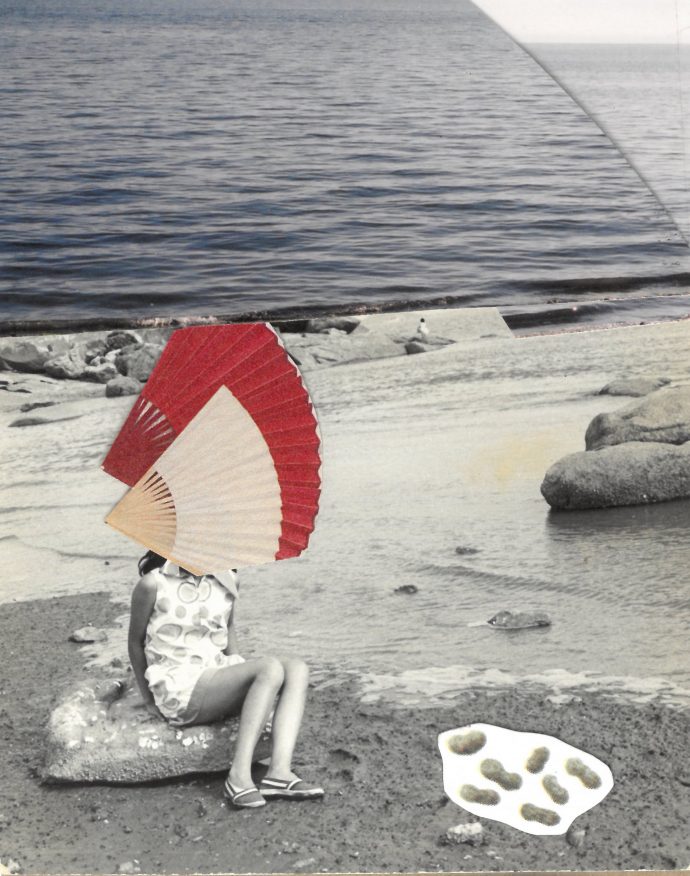

In the photograph she perches on a large, flat rock, barely lapped by a ripple of waves visible at the right edge of the frame. She appears to be leaning back on the rock for balance, but because she is lithe and long and the rock not very large, a small, bent awkwardness interrupts her pose, so that she appears not as if balancing gracefully on outstretched arms but rather as if pressing down uncomfortably, a palpable cramping discomfort intruding into the stillness of the seaside photograph, the feeling of an object on the verge of collapse.

When I am twelve years old and we move to a green and desolate cul-de-sac in the white suburbs, every afternoon after school, a gaggle of mothers assemble to take a leisurely walk around the block, and in the seven years that I live in that house as my mother’s daughter, they never once ask my mother to join them.

In this way, I understand my mother is not like other mothers. So, too, does my mother enjoin me not to be like the other girls, and by other girls, she means the white girls who are loud and slutty and disrespectful. Why I would aspire to be like a slovenly white girl is a question beyond my mother’s understanding, just as she cannot comprehend why I insist on attending high school football games (when you hate football) or plead to be allowed to go to Homecoming with a cloddish, crude boy who gets bad grades (because he asked me).

My mother’s and my alikeness are entangled with our aspirations, which are nothing alike.

In the script, the American daughter is stronger, more arrogant, and more sure-footed than her weak, overlooked, self-doubting immigrant mother.

But this is backward. Stripped of aspiration, likeness is but a banal descriptor.

When they humiliate the daughter, she stays up all night, restless with bewilderment, wondering: what makes her so different, what makes her so wrong? But when they try to humiliate the mother, she wonders: what makes these people so stupid, ignorant, and selfish?

And the mother pities them in that brief moment before their faces recede into the sludgy backlit scree of all that is inconsequential and has nothing to do with her.

I want to know whether I am like my mother. I have to ask myself the question while she’s here. Once she is gone there will be the irreparable rift of my aliveness that will make us too different from one another, an epistemological obstacle I will not be able to clamber over. As long as she is alive, we are both survivors, and this is the firm baseline of our alikeness, one that adheres us together as if superglued.

I have survived being her daughter, and she has survived being my mother, and together we have survived the hostile glances and reprobation of everyone around us who found our ways of being mothered and of mothering incomprehensible, pointless, and pig-headed.

Was she very strict, asks my therapist.

Why so ungrateful, asks my mother’s friend.

In the script, the American daughter is self-aware and goes to a therapist to keep fine-tuning this self-awareness, while the immigrant mother cannot contain her incredulity, not necessarily at paying someone simply to talk to them, but at intentionally choosing to ponder a bad thing and then further choosing to go over and over and over the bad thing again and again rather than making the far more rational choice to banish the bad thing from all thought, speech, and memory.

When I was a child, she’d call me loudly to come scrub her back in the shower with a rough red glove. Sloughing off the dirt and dried skin we called black noodles. Her hands were beautiful, and her fingers already subtly hooked, like rakes in parched fields. I have the same hands now. When a bad thing happens, she likes to go over it over and over again and again as if transforming a note that can’t be swallowed into some janky song, squeezed through a cracked and broken reed. If I picture her body as landscape, it is a broad meadow dotted with stubborn green weeds. You will have picked a bouquet of these burst, weedy flowers before realizing—they are the blinking lights of small neglected engines. Friends say my mother is beautiful, chic, elegant, and sweet. I have stood in the kitchen rigid with anger and made my mother weep.

Within the closed principality of likeness comprised of my mother and me, it remains impossible to say who’s the foreigner. We are the sole citizens of a country of two, blood-bound yet each indecipherably Other in language, where we both steadfastly adhere to furious idiolects,

like when my mother texts why are you so mad I didn’t mean to make you mad and I text back I’m not mad at all there’s no need to get upset and she texts back who’s upset I’m not upset why are you upset and I text back I’m not upset you’re upset.

In the eulogy for my mother, I say

old slights can never be repaid and that’s a fact. I say

she made her choice then stuck to it: to sail blindly forth on trust, seconded by internal rage. I say

enraged by the mere sight of snot on children’s faces, she wiped our noses so often and so roughly that thinking of it makes my nostrils sting. I say

the cracking sound she made when chewing gum was a sound I tried to imitate for years, clacking my tongue obnoxiously against my palate. I say

like her, I am not the forgiving kind.

My first friends were the children of my mother’s friends, Mexican, Ecuadorian, Venezuelan, Pakistani, Irish, Greek, Lebanese, Korean mothers, our harbor against angry fathers, who came home exhausted from terrible jobs, struck us, threw things, and yelled. The fathers’ rage was externalized into a crashing opus of hands and fists, while the mothers’ rage burned bright interior bonfires, fires that lit our way, by whose lights we might glimpse what we would later become, far away from our mothers and fathers. The mothers did not strike us, nor did they defend us, their pity tempered by the memory of worse fathers.

We were tall, short, skinny, chubby, brown, black-haired, wily, smart, lazy, disobedient, docile, harmless, malicious children, all alike. Our lives were so alike, our fathers so alike, their anger alike, the way their differently accented voices flared into sudden rage alike, our mothers’ insolvency alike, the helplessly competent way they did everything that needed to be done while failing to earn a penny to ease the financial burdens of our pissed-off dads, alike. When one of us got lice, we all got lice. The mothers argued about whose child was the cause, but without conviction. Each knew it was the other’s child, and each was so certain she was right, there was really no point in arguing.

Our fractious families, our rich white classmates, the hostile clerks at drugstores where our mothers sent us with a quarter to please just go away, the sidewalks not made for walking anywhere, the rec room where the chairs were always soiled, the playground swings where we clustered to make our secret, arrogant, definitive plans, here where friendships were arranged marriages, their convenience and suitability undeniable. None of us belonged in America’s genial, white-hot world. Our alikeness forced open the doors of like, barreled us straight into a cloister of sticky, jealous, turbulent love, where we wrestled ourselves into existence.

There was no difference then, between my mother and me, between my mother and her friends, between me and my mother’s friends, between my mother and my friends, between my friends and me—I could have sworn that my mother and I were the same person, our silhouettes crushed together on the illustrated timeline of the Cycle of Life, so that the figure representing the Age of Childhood superimposed on the Age of Adulthood, creating the palimpsest of Us, a two-headed, four-legged, four-armed creature glumly stuck in an Age of Child-Adulthood, speaking out of two mouths without discerning anymore which one was accusing and which one was denying, which was attacking and which defending, which confessing and which exulting at the confession: I knew it.

The story of belonging is also: wanting to be so like the others, in the hopes that by knowing them, you could also know yourself, but without having to do any extra work, because what a dizzying pleasure, knowing them, and what a mind-numbing slog, to know yourself.

And if asserting a choice was what made you different from the others, we made the choice to be unconcerned about choosing. We had none of us chosen our mothers, our cramped apartments, our bullies or fathers, our stupid haircuts, what we ate, what we wore, and yet here we were, doggedly alive—I like, I don’t like: this is of no importance to anyone, this, apparently, has no meaning. And yet all this means: my body is not the same as yours.

Here’s one issue with the eulogy: properly speaking, my mother has had no vocation

or else it might be more truthful to say that being a mother has been her sole vocation, and we all know that while this sounds kind of lovable, in the broader calculus of the world, it adds up to a big fat zero and interests no one.

The book about the death of the mother is doubly anticipatory: it exorcises not only the future death of the mother, but also exorcises feeling of being unreasonably so very angry at her apparent obscurity, which as it turns out, is very congruent to the unreasonable feeling of rage that often arises from having her as a mother.

In the eulogy about my vocationless mother, I say all that my mother has for years refused to say, and because she remained silent so long, I say it now louder than necessary, more stridently, and with more malice. I imagine the words issuing directly from the mouth of my mother, as if after death only her mouth has been exhumed, an open vessel that could be crammed full of odorous, rotting fruit. What woman here is so enamored of her own oppression that she cannot see her heelprint upon another woman’s face? The lightning bolt of anger I have so often seen seared across the face of my mother could also be this. The decades-old imprint of my heel.

In another way, my mother is, above all others I know, most certain to die perfectly fulfilled. In fact, I think her vocation was not to be my mother at all. In fact, when they asked her, in early childhood, what do you want to be when you grow up, I feel certain she replied, not actress teacher nurse mother wife but rather: alive.

Clever cookie. And in this vocation she has achieved, is achieving still, unmitigated success.

What of my vocation? My vocation has already rejected me, it does not want to know about me. If part of my vocation is to be my mother’s daughter, surely am I the worst of my species, to be writing about the death of the mother before my mother has died, as if to hasten that end.

Then again, to imagine being the worst kind of daughter is a fresh, delicious thought, one toe languorously dipped into the neighbor’s swimming pool on a hot day. Sweet, cool relief from the humid choke of always striving to be good, loving, understanding, even adequate. A world of possibility, the expansiveness of what I could be, if I were the worst. I could do anything I wanted.

Wouldn’t my mother also like to be a terrible mother? Wouldn’t that feel so juicy and busted? When my mother was young and still living in Korea, she shoplifted a carton of milk from a grocery store, while I sat cluelessly gurgling in the cart, a mere baby. The clerk who caught her scolded her especially for stealing in front of her child. She was chastened and promised never to do it again. Wasn’t she also thrilled? Didn’t she give me a sly wink as she almost got away with it? Didn’t she say I’m sorry I’m so sorry while silently cackling?

Years later in America, home alone with the children, she found herself in need of an ironing board. But she had no car, and it was obvious she couldn’t walk home from the store pushing a stroller, holding a toddler’s hand, and carrying an ironing board at the same time. Taking stock of the situation, she made a swift decision. Put the baby in his crib, ordered her daughter (me) not to open the door to anyone, and left in a flash. All the way home from the store she sweated and struggled, half-running so that the ironing board banged painfully against her ankles, causing deep blue bruises, thinking my babies are dead my babies are dead I left them alone now my babies are dead.

But neither shoplifting nor momentary neglect make a bad mother. What’s a mother to do! Sometimes mothers are compelled to briefly endanger their children in the service of satisfying some material or psychic need: whatever the cause, according to script, the mothers act rashly, feel sorry, then express their apology through sincere contrition, misplaced resentment, or overwhelming regret. Or they’re just punished.

I am wondering, though, about not feeling sorry. Joyful smear of not-sorry feelings. Those feelings my mother couldn’t reconcile, even to herself. Feelings that defied classification, or were inadmissible, feelings whose sullen, unyielding opacity caused a scorched jab of pleasure each time she gingerly poked.

Wouldn’t it reassure me, when I have these feelings myself, to think:

I’m just a terrible daughter, with a bad mother.

What was she like, roaming carelessly in a foreign city, by the sea?

Was she careless, ever? Carefree? What’s the point of holding such a cramped and uncomfortable pose, perched on a rock? Was she anxious for the picture to turn out well? Is her expression pinched with irritation (unhappy) or squinty from too much sun (happy)?

Another image: my mother’s eyes narrowed, enraged. What does she see then, when my face is what she beholds? If I could wear her face for a moment, could I finally see myself?

What happens to the cruel word set adrift on the river of I don’t remember?

The photograph is black and white, four by six, framed in white. She wears a collared minidress, slightly flared at the bottom, in a cut very typical of the era, printed with crisply undulating geometric shapes, whose palette is difficult to envision freed from their angular sobriety of shades of grey. Chartreuse and rose, coral and teal, perhaps. Big bright saturated clashes. Her hair is very black and forms waves that frame a round, pretty face, caught in an expression of mild surprise. Not an unhappy surprise but without, strictly speaking, much evidence of happiness either.

On the two hundred and ninety-third day since I last saw my mother, an Asian American woman about my mother’s age is shoved to the pavement near Times Square in New York City and repeatedly kicked in the head by a passerby who shouts racial epithets and: go back to where you came from. Most impressive are the stolid doormen who appear on the surveillance footage, which I view accidentally, clicking from one link to another, because I have no desire to see such images, who observe the beat-down through the open door of the building, and then, in observance perhaps of her prone and shaking body on the sidewalk, shut that door.

What is expressed again and again as I follow link after link:

that could have been my mother.

To date, there is no one alive who does not have a mother, whether that mother is known, unknown, material, abstract, concrete, visible, invisible, merely an accident of biology, or metonymic for the emotional fabric of the world. We have our belly buttons to prove it! Every mother beat down on the sidewalk is therefore all of our mothers. Every mother who is kicked in the head that could have been my mother.

It will surprise no one to hear me admit my many faults. But the faults the others think I have, and the faults my mother thinks I have, are different.

I thought I must be weak or damaged, not to feel at home in the world, to feel so out of place, unseen, unsafe, everywhere. My mother’s understanding is that feeling unhomed, unseen, and unsafe anywhere in the world and yet surviving is precisely my strength.

If I were a good daughter, I’d send my mother her eulogy, while it could give her pleasure. Give me my roses while I’m still here. I’d enumerate her kindnesses, make mention of the small gestures, her quirks, a tic in her speech, tiny, intimate details she’d feel happy I’d even noticed. I’d make her feel she’d been noticed. She’d feel consoled at not having disappeared into silence. In the eulogy I would not say: I asked her to tell me, and she did not speak. When she spoke, she said: don’t repeat this to anyone until I am dead.

Three hundred motherless days. Mother,

to whom I am bound by likeness,

who will one day eventually die, I am trying to get on the inside of what it is like to be she-who-has-you-as-a-mother, in order to account for what it means to be me-who-is-your-daughter, to learn the inside so that I can learn the beyond, to write through and outside my own experience, so that I can account for and be accountable to the others, so as not to harm them, so as to live.

What it means to me to wear your face is surely different than what it means to you to see me borrow it. I’ll say this now before there is no you to say it to, during the long winter of your unforgiveness, the brittle summer of your not forgetting, Mother

we are water and oil, peas in a pod. When I was a child and you were inconsolable, I thought my taking care of you remade me as a mother. But now that I’ve grasped the barbed task of actual mothering, I’ve been remade a child, and you a mother, swept back together into a childhood bereft of children, where you and I were always alike, thick as thieves, grappling with the paucity of the spoils we stole from the unloving world, our loving saying you as mutely as the stone that nevertheless determines the direction of the current,

what you gave me: aloneness, and its capacity to mimic feeling safe-from-harm. Now that I have everything and anything you wanted ever, even the gaping mouth of your sadness, harboring the wickedness of teeth. There is also some landscape within you in which you are always alive, alone, and evenly breathing—the place that exiles me and to which I also must return, a figure leaning on a rock, a black spot of ink bored into the sand, whoever it was that you were when you shone as brightly as the aberrant luminescence of death’s yearly visitation of the ocean,

in order to unstiffen the swaddled curve beneath sheets that will one day be your body, I forgive you now for having never forgiven yourself. To have seen you cry cursed me with a talent for confession, epic in sadness but likewise in mythic detachment. Being mothers, we are bound to obey the heroic strain, no matter our desire to walk lightly over crusted snow, leaving the barest impress. Everyone knows I was born out of your body. But I, too, guaranteed your living. I write to tell you our being here together has been a meeting of like minds.

When you are gone, having said so little, it will then be up to me to say.

I am the one who will remember best, who will say your name last, who will accompany you into the second death. The last time I pronounce your name, I will be loosened into the flat field of solitude’s char, free to wander. Let loose into the wilderness of visionary self-care, pressing forward with my own survival, emptied at last of regret, as if needing only rain barrels lushly full of desert rain, the fire pit with its fragrant cedar, so much joy, Mother, that no one else but we might enter.

Notes

It is only when you lose your mother . . .

Saidiya Hartman

“I like, I don’t like”: this is of no importance to anyone . . .

Roland Barthes

What woman here is so enamored of her own oppression . . .

Audre Lorde

My vocation has already rejected me . . .

Natalia Ginzburg

Youna Kwak is a poet, translator, and teacher based in Southern California. She is the author of a book of poetry (sur vie, Fathom Books, 2020) and two books of translation (Gardeners by Véronique Bizot, Diálogos Books, 2017; Daewoo: A Novel by François Bon, Diálogos, 2020).