The first suicide I knew was half-Asian. We lived in the same town, went to the same high school. She was a girl one year younger than me. She killed herself the year after I graduated. That she killed herself and was half-Asian was coincidental. Or, no one made the connection. But I could not help making it. I could not get it out of my mind. The girl was also, in the cloistered wilderness of the small town in Connecticut where I grew up, the first person, aside from my sister and myself, of whom I was conscious of being half-Asian. Knowing, seeing someone else who was half-Asian, like us, awakened in me a sense of what I was like. The sense was false, or adulterated, coming as it did from the outside. Our town was white. Everyone who was less than or not at all white stood out in relief. We had that automatically in common. Our small number provoked categorization. But the whiteness worked both ways. It abstracted us from the categories to which we were falsely assigned so that we were in between, nowhere. There were a little over 20,000 people in our town. Two percent were Asian. My sister and I, half-Japanese, were two. Our father, Japanese, was three. The girl who killed herself was four. Her mother, Filipina, was five. Her father was white. Their last name meant: one who cares for the herds. Also: servant. Her name was S. She hanged herself from a tree in her parents’ backyard. It was late September 1997. Even now I see an enormous lichen-colored granite rock among birch trees with bright green leaves and S’s body hanging slack like a coat. I do not imagine her parents were able to look at their backyard without seeing their daughter’s body hanging from a tree—their daughter first, then a shape, a black hole, burning at the edges, drawing everything into it.

From the beginning, most of the half-Asian people I knew were half-white. In that cloistered wilderness, where only 2% of the people were Asian and the majority of people were white, whiteness was law. Homogenization and color blindness served a crucial paradox: to trap the person of color in an airless space, wherein identity was exacerbated, inflamed, as if the person were glowing, then hemorrhaged out, until nothing remained visible. Even shadows were made to withdraw.

S and I also had in common the fact that both of our families had, a few years earlier, and for an entire school year, hosted exchange students, teenage girls from Germany. Petra lived with my family. Stephanie lived with S’s family. Petra and Stephanie were friends. Their friendship was based on their status as outsiders among their American classmates; they had little in common, but were forced, by their mutual culture and language, to always be together. That two half-Asian families hosted German girls in late 1980s Connecticut strikes me now as an oppressive social configuration; all the elements were, in their time, oppressive: Connecticut, the late 1980s, two teenage German girls who had no friends but each other, living with half-Asian families in an otherwise cloistered white wilderness. S and I waited, one afternoon in the hallway of the high school, for our German sisters. She was wearing a dark blue sweater, her back against a cream-colored cement brick wall. She had a sly, precocious smile.

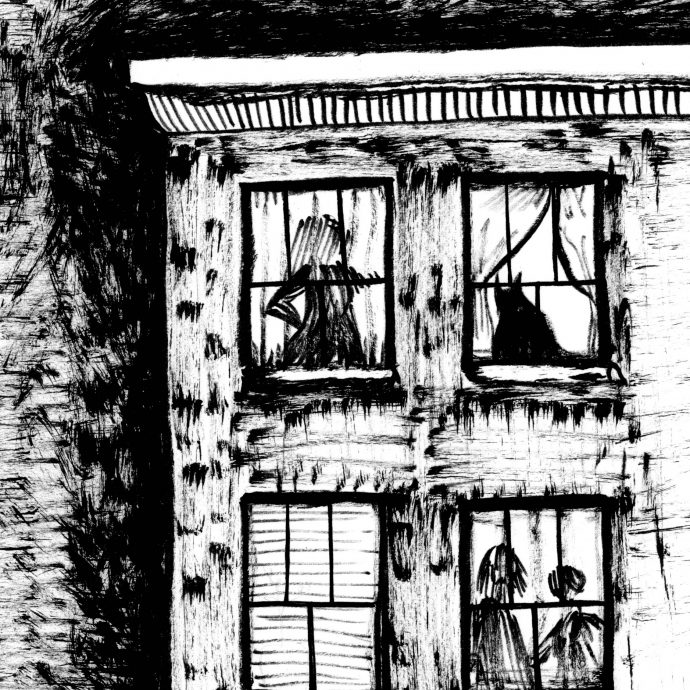

It was said that when S hanged herself, her mother was in the house. I can see her mother’s short black hair, a window on the wrong side of the house; a room without windows; a room on the front side of the house; a room on the back side of the house with two windows looking onto the yard; a house that is one enormous room with countless windows looking onto the yard; the shadows of trees on the wall.

Who saw S’s body first? How did she hang herself? My friend Adam knew her—maybe he remembers:

I heard her father was home when she hanged herself. I pictured her using an inch-wide rope. I wonder if she climbed up or used a chair. Sometimes I imagine it overcast and muggy, sometimes clear and breezy. The tree is always the same: an old maple with a low, horizontal branch. I imagine her swinging from it as a child. I had no idea she was Asian.

I told him: half-Asian, though telling him half felt compensatory. I did not think that he would remember S’s suicide. Or I thought he would say it didn’t happen, or not like that. The details are acute (an inch-wide rope) and idyllic (a chair on its side beneath an old maple). Impressionability attends to S’s suicide, and every time a chair appears, or the tree changes, the suicide is recast, reenacted.

When I was young, I had fantasies of tying a large, heavy rock to my leg and jumping into Round Lake, at the top of the hill where I lived. It went like this: the rope pulls at my ankle, and I twist with the large, heavy rock to the bottom. But the fantasy included its failure: I panic and rise to the surface, climb up the wooded slope of the lake to the road, and never mention to anyone what I have done.

Would I have sunk with the rock? Would the rock have been heavy enough? Would it have slipped out of the rope?

How deep was the lake? How cold was the bottom?

Did I open my eyes? What did I see?

I thought about the girls I knew who attempted suicide. All white, all of them friends. A was holding a knife to her chest when I entered the dining room. All the lights were off. Her father was upstairs. Everyone else had gone home. I remember the knife and the look on A’s face. Not pain, but the featurelessness of a person who had slipped back into the wrong end of childhood. She was institutionalized, several times.

D ate pills. This was sometime before or after she got in a fistfight with her mother. She, too, was institutionalized. Z drank a bottle of rubbing alcohol. She called me from her closet to ask me if she was going to die. She was institutionalized also.

My female friends seemed much older than my male friends, more experienced, already exhausted by the world. I visited them in psychiatric hospitals in the woods. I sat with them in sterile kitchens, at sterile dining room tables, in sterile living rooms—anesthetized replications of domestic settings where they were meant to perform their recovery.

An empty dining room at night, a closet, a bottle, a smaller bottle, a throat, an esophagus, a stomach, the bottom of a lake reached as if by elevator, compressed, a corpse compressed, standing upright, but I envisioned suicide being larger, more spacious. Instead of killing myself, I will disappear into the mountains, I thought. I did not understand.

Is some part of suicide satisfied by committing it as a fantasy? I was captivated by the scenario: a shadow on water, a body disappearing into it.

The lake was a mirror, momentarily. Then neither my body nor shadow remained. It was not transmigration; the lake, dark, was a more inhospitable form of the world I was jumping away from—suffocating, yet contained, without color or range.

The wooded slope was suddenly there, as if the walls that had contained me had turned sheer and were melting, revealing the wild fringe of a border. I crossed over; I climbed up through the woods. I started running along a path, a path beaten down by my running. I was catching up with myself. I did not remember the trees having leaves. Only when I looked up did leaves form the sky. There were no flowers. I ran in circles. The circles distended. The woods shrank. I stretched my body across an enormous lichen-colored granite rock among birch trees with bright green leaves. I stepped from tuft to tuft of wet grass in a swamp. There were liver spots on the trout lily and the voluble silence of jack-in-the-pulpit. There was nothing behind me, nothing behind my running. I could not conjure where I had come from. The woods were impassive. The sky was very low. The curvature of the earth was immediate. All of it felt like: preparation.

S’s classmates remembered her as an athlete. That is one thing she was to people. She ran cross-country. An article that came out in the local paper two years after she died (April 1999) said she was popular and pretty and a good student. Her teammates dedicated the rest of the season to her. They said her memory would inspire them to run faster. Did her memory inspire anyone to run slower or stop running altogether? No, they were inspired to run faster, away from her body. [B]ut they also knew her absence would be uninspiring. Inspired by her memory, uninspired by her absence: it is semantics, but I read her memory as their memory of her. That is, their memory of her before she killed herself, when she was an athlete, uninspired yet by her forthcoming absence. The most obtuse yet predictable sentence of the article is one that treats S’s suicide with willful blindness and naïveté: Her life seemed too stable for such a sudden end.

Growing up Asian in a white body or growing up white in an Asian body or growing up Asian in an Asian body surrounded by white bodies or growing up Asian and white in an Asian and white body in a white town in America, is, within the kaleidoscope, violent. But the violence is often indecipherable, because the break is not always visible. It often expresses itself as self-hatred. I thought my white self would carry the weight. I thought I could pass. But my white self occupied my non-white self and forced a rift, a pulling away. I was halved, yet left to bear the emptiness in the middle.

Violence (self-hatred) visited me like a light shining through my bedroom window. It separated me from my white mother and my Japanese father. As models, they were incomplete. I thought I was white, but did not recognize white people in myself or myself in white people. I thought I was Japanese, but did not recognize Japanese people in myself or myself in Japanese people. I did not turn to my mother and father. I did not approach them. It made sense to me that they got married on the side of a mountain in Switzerland, a neutral country. My sister and I were the offspring of that desire for neutrality.

September 21, 1997. When I envision the woods, it is late fall. But when I envision S hanging, it is spring. Even now I see the backyard, tilting into the trees, white sky low over the ground. S’s father wore glasses and had a mustache. Her mother had short black hair and pearl earrings. I am describing any man and woman.

Did S’s parents cut down the branch? Did they have the tree removed? Is it important to keep the landscape of suicide clear and uncluttered, so that the body does not become another detail in the landscape?

Everything in the landscape of suicide swallows the dead. The windows of S’s house, colored with the reflections of everything above S’s head.

A window is propped open. The windows are closed, as a rule. Or the windows are kept open, in case?

There is no longer any reason to open the windows.

The man and the woman live in a house on the lip of a bowl. The moon rises out of the bowl, up through the trees, scrapes across the sky, suspending a trail of cells over the roof.

Did their grief become a mission?

Insoluble. In which a dream is occasioned by a sound.

One of them was in the house. One of them turned away.

The man and woman have melded with their house, a monolithic gravestone, inscribed with waiting.

Obtuse movements can be seen through the windows. A man and a woman follow each other from room to room. The house has succumbed to its own lack of security. The woods have moved in. The man and the woman are walking in circles. They are never in the same room at the same time, always a step behind, catching glimpses of each other’s heels, the backs of their hands. They wander blankly into a mirror image of their lives in which the backyard has not been stained. Over time, the man and the woman become indistinguishable.

What happens in the final moment? Do our mothers and fathers become one—one colorless angel, one incorrigible sphinx? It seemed S’s face was instantaneously withdrawn, but no, her face, and with it her shy yet precocious smile, was dispersed. Neither her father nor her mother could find her body on the wall, no matter how hard they pressed their hands into the shadows.

Brandon Shimoda’s most recent books are The Grave on the Wall (City Lights, 2019) and The Desert (The Song Cave, 2018). He is currently researching/writing—more often disintegrating—a book on the afterlife of Japanese American incarceration. “The Shadows of Trees on the Wall” is from a collection of essays called Vanishing Clarity (in-progress, unpublished). He lives with the poet Dot Devota and their daughter Yumi Taguchi in the desert.