The Old Lady and the House

Forty years ago, Lucy bought the land, split the lot,

built two houses, sold one, lived in the other.

Ten years ago, we moved in next door. For months

we only saw Paul, her husband, faithfully out for a smoke

on the front lawn, with Sue their playful grey Shih Tzu in tow.

“She loved the previous owners’ kids,”

was his welcoming remark, her poop across our lot.

Our son was one-year old, Paul

was about to enter his seventies, and Lucy,

a good few years older, was fitter,

more vigorous, but neither walked their Sue.

Paul watched the chronicles of the neighborhood,

a paradisiac Bantustan, our little city of god.

A year earlier Fatima and I visited San Miguel de Allende

to restore our minds in eco-friendly destinations.

She was five months pregnant.

We were living in an apartment complex

that a hurricane would also drench

after toppling its papier-mâché chimney.

In San Miguel, the Gringo-run B&B was a fairytale

Structure, out of the palaces in Sentra.

Half-owner, the local wife cooked us Christmas

dinner, denounced the natives who “like being poor,”

as her husband radiated his traumatized Californian youth

through a book’s help

that scored all religions

to a barometer of Zen.

Islam scored lowest.

Paul was a veteran

with an enlarged prostate.

His advice was that I should “watch out for them”

who blow my live oak leaves, they’re bound

by law to dispose of the waste

“free of charge,” leave none

of it in black plastic bags on my curb, an eyesore

for other residents. A month later, I asked Jesus

(leader of the landscapers who’d come

to the US during the Zapatista Revolution)

to trim the live oak branches

including those that straddled the corners of the two backyards,

and Jesus remonstrated

that as dogs and fire hydrants are as good

as apple pie, he wouldn’t cut a single branch

that covered a parallax

of that man’s yard. “Your neighbor, he’s,

how you say it,” as Jesus stuttered

a rhyme with a cystic illness

attributed to Ra, the ancient sun god.

I corrected Jesus’s pronunciation.

Paul’s health began to change. Lumbago

herniated his golf swing.

He quit smoking. The body

that nicotine infused turned diffuse.

His abdomen grew rotund.

He contracted diabetes.

Soon there was no more small talk,

no navy stories. I’d find Paul outside,

his shoulders closed toward a street

I couldn’t call him back from.

Dementia and hospitalization

started their record of his life.

Lucy struggled with the decision to put him away

in a nursing home. “I remarried a younger man

so that he’d take care of me when I’m older,”

she said woefully to me, “and I hate fat people,”

she added with a shiver as she bearhugged herself.

Thin throughout her life,

and always in proper robe on the grass,

and if intercepted in greeting, she’d quickly apologize

for her hair and the Texas sky,

though I’d never seen her or Paul

out to Church on Sunday.

Paul was now well cushioned

into his dying. When he stopped

recognizing her, she stopped visiting him.

I began to see her daily, watering

her yard and plants, mowing her grass, a sloth

born a bee in a solo hive.

One day she knocked at my door,

her voice trembling, and I let her in.

She said her landline was out of commission,

that she’d just been released

from the hospital for hypertension, a minor

stroke, a fibrillation.

I plugged her phone back into the wall.

I thought her end was near. Our niceties atrophied.

She was the tea-drop-stained

figure in a photo. She no longer heard my car

come up the driveway, my doors slam

open and shut, my half-hearted hellos.

That was five years ago. And yet

when she and I had hardly exchanged a word,

whenever she’d run into my mom outside our front door,

Lucy, unprompted, would praise me. A testament

to her classy decorum, thoughtful

of another mother’s heart.

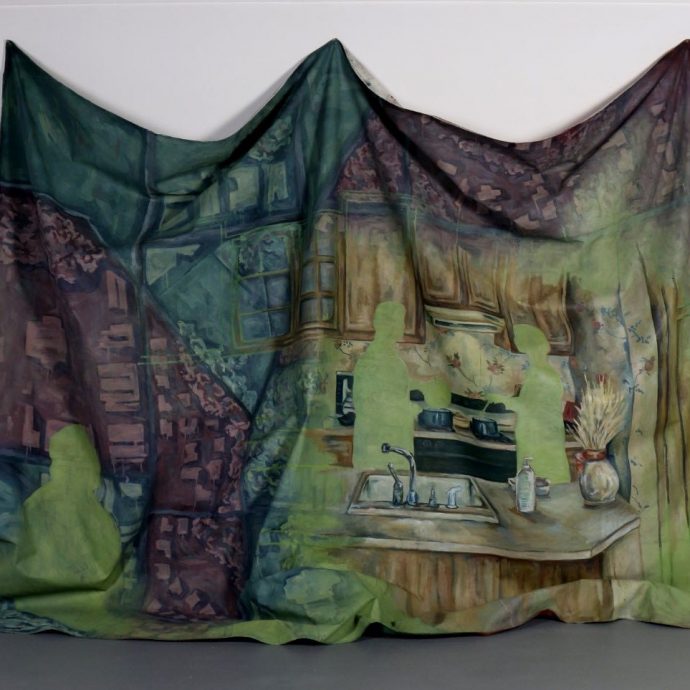

Then rain fell biblical, anthropogenic.

And all the houses on our street flooded,

left us hydrophobic of a swollen sky.

When water receded,

everyone on the street walked out to talk

with each other, nouveaux ions in calamity’s bonds.

Lucy’s son

came to her rescue

and cut to the chase:

a woman of 90 can’t live

in a house under repair

unassisted. The property

would be sold. But his mother

wouldn’t sanction the sale,

and a few months later moved back in.

During remodeling, amid the rubble

that lined her front lawn and engulfed the white crape

myrtle that stood on the border zone between us,

a burgundy leather shoe

bulged like a boat.

It was Paul’s right edematous foot.

For two months it stayed there waiting

for the city’s waste management services.

Twice I stood by the heap

looking for the left shoe,

and what would I have done

with it had I found it?

Lucy is still living

in her house

and will die there.