The last act is tragic, however happy all the rest of the play is; at the last a little earth is thrown upon our head, and that is the end forever —Blaise Pascal

My friend Rafael says that the thing about dying in New York is, it doesn’t last very long. I tell him I’m not sure I know what he means by this, and I’m not sure he knows, either. “The city that doesn’t sleep,” he continues, fully embracing the cliché and looking slightly pissed—he pretty much always looks mildly to moderately pissed—“doesn’t waste time mourning its dead. Life is fast here, and so is death. Stop a second to look back and you miss both.”

He pauses to follow a pigeon fluidly descend from a second-story ledge to perch peacefully on the rusted top of a mailbox on the corner, giving his statement a moment to settle as we hustle across Houston Street against the don’t walk signal and start up Second Avenue in the face of a biting November gale that seems to have suddenly swooped down just to make our brief walk a little more uncomfortable than it has to be. “If you want to die slow,” he says, as we weave through a raucous gaggle of schoolgirls marching toward us like drunken soldiers on leave, “go fuckin die in Florida.”

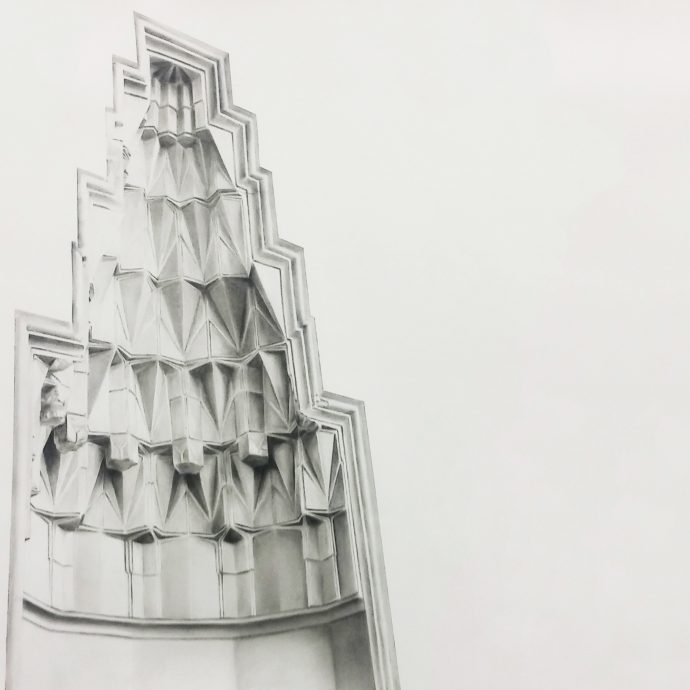

This last sentence he sort of spits at me, but the very next second he drapes a brotherly arm around my shoulders and ushers me away from the outside cacophony into the churchly quiet of the cavernous lobby of his mother’s building, a vacant, vault-like open space that was once the lounge/check-in area of a tony hotel back when this strip of Second Avenue was informally but universally known as the Jewish Rialto, lined from Houston to 14th Street with venues for Yiddish theater, vaudeville, and burlesque. The building retains a kind of vestigial grandeur, an elegiac elegance, a pale testament to its proud past, but there is something distinctly sad and a little spooky about it. I can imagine plush velvet couches and maybe a small bar in the corner, people ambling about in their mid-century best, getting ready to take in a show or go up to their rooms with a bottle of Manischewitz and a freshly baked babka. Now it’s no more than a big mottled marble floor whose echoing barrenness is a stark study in contrast with the pullulation just outside on the avenue. There is nothing but a row of mail slots against the wall where the reception desk would have been. Austere in its obsolescence, it is just another charming but crumbling tenement patiently waiting for the older occupants to quietly and politely die off so the landlord can renovate and raise the rent.

Rafael is definitely onto something. Death does seem to have a shorter lifespan—so to speak—in New York. It’s not that the city’s dead are forgotten so much that, once they’re gone, it’s as though they were never here. Of course, this is death’s unequivocal truism: we’re all so quickly and thoroughly erased from the page that no character, however seemingly central to the plot, remains relevant for long. Even the greatest of New Yorkers are mostly remembered eponymously, with little relation to who they were or the lives they led: Jacob Astor has a Place; Peter Cooper has a Union; FDR has a Drive, etc. To live in the Empire City is to surrender one’s sense of self—and often sanity—to an abiding sense of place, to the ineffable hum and humbling of history in all its breadth and narrowness, its longueur and immediacy, and to die here is to cede one’s soul to the maddening scurry of humanity, to the sound and fury and spectacle of the world. Regardless of how long and drawn out the dying process is, the actual dying—the moment of death, the instant of one’s passing, expiration, extinction, the complete cessation of life processes—happens in a flash. Whether you die after a years-long bout with cancer or meet instant obliteration in a blazing collision with a speeding freight train, the actual transition from life to death, from living human to lifeless corpse, is the same split-second conversion, like turning off a light. Out, out, brief candle!

But according to Rafael, at least, it is something different when it happens in New York.

This is why he had absolutely no qualms about taking me to the vacant apartment of his mother’s recently deceased upstairs neighbor, Deanna, a couple of days after her funeral, with the express intent of scavenging its contents.

For Rafael, there was no impropriety in this invasion of the newly dead woman’s residence, no sense of trampling hallowed ground or disrespecting the departed. Underlying the façade of modern civility is the law of the jungle; if you can’t defend your stuff, it’s open to despoilment. In his mind, only the sidewalks are sanctified, only the structures significant. The brick and mortar of the city itself, though ultimately as ephemeral as anything organic, are all that matters. Everything else, including the people who inhabit the place, is incidental. Seasonal decorations, at best. Generations come and go, but the city abides.

Just outside the door to the unit, Rafael stopped and sucked in a deep intake of air, held it as though analyzing its olfactory origins, released, and stared at me. “Smell that?”

I didn’t smell anything other than the typical sour scent of poorly ventilated

hallways and maybe the faint tang of cooking oil, but I assumed he was going to say something vaguely dramatic like, That’s the aroma of fresh death hanging in the air, so I just nodded complicitly. Whatever it was he smelled, I was going to smell it too.

“Cats,” he hissed. “Filthy street felines. She lived with six of them. My mother found homes for two so far and she’s still looking to place the other four. Meanwhile they’re upstairs meowing all fuckin night, leaving their fur everywhere, scratching shit up. It’s driving my stepfather crazy.” He scanned the corridor and leaned in close to me and whispered (though Rafael’s whisper is generally about as loud as most people’s indoor speaking voice): “I say give the damn things to the Koreans in 2B and let them make stew out of them.”

He cackled at his quip, and I resisted the urge to correct his racist stereotypes and point out that it’s the Chinese who are wont to eat cats, while the Koreans prefer canines. “I hear cat meat’s not that bad, actually,” I said.

“Meat is meat.”

“Probably tastes like chicken.”

He turned the key in the lock. “Exactly.”

Besides the general curiosity of any New Yorker to see another person’s living arrangement and compare it to one’s own, I was lured to the apartment by the promise of stacks of abandoned books and some nice art prints. By the time we got inside, however, it was clear that other people had already ransacked the place. Outlines in the dust on the floor attested to furniture recently removed. Post-its stuck on other items marked prospective ownership, like layaways at a department store. Rafael’s brother Luis had reserved a large walnut chest of drawers. Someone named Martha wanted the rolling kitchen cart. Eric had staked his claim to the brown leather recliner in the living room with his name in thick black marker in all caps and three exclamation points on a perforated piece of loose-leaf paper taped horizontally onto the center of the chair’s upright cushion. Rafael himself was planning to take the bedframe and give it to a friend of a friend on Staten Island. I asked him if he felt at all weird about taking a dead person’s bed.

“Why would I?”

“Because she slept in it.”

“So what? She didn’t have the fuckin plague. Plus, she didn’t die in it. And even if she did, she slept on the mattress, not the frame. And someone else already took the mattress. Which is a shame because it was one of those new expensive pillow-top adjustable kinds. Me and my brother helped bring it up so she didn’t have to tip the delivery guys.”

“Where did she die?”

“In the bathroom.” He pointed down the hall. “Which reminds me. She had a nice shower caddy. I hope it’s still there. I could really use one of those things.” He rushed over to the bathroom, from where his voice echoed, “Shit! They got it.” He emerged holding a multicolored marbled soap dispenser. “Fuckin vultures. I’m surprised anything’s left at this point.”

Rafael’s mother and several others in the building had had copies of the dead woman’s keys in order to check up on her and take care of her six cats and one dog when she was unable to do so herself, which was most of the time, given that she’d been suffering from a cocktail of serious illnesses, including AIDS and cancer. As her sickness(es) worsened, she spent more and more of her days in bed, then the hospital, and finally the hospice, so her apartment had basically been abandoned well before she’d left this life. Deanna died intestate, with no living family members, no heirs or offspring to inherit whatever possessions she’d left behind, monetary and otherwise. Initially, there was talk that her mother, from whom she’d been estranged for over thirty years, was still alive in an upstate nursing home. But while the estranged part proved true—Deanna had not had any contact with her mother in decades, after she had abruptly cut ties with her daughter upon learning of her penchant for dating black men exclusively; not African-American men, but African African, men straight from the sub-Saharan heart of the continent, the bigger and blacker the better, which did not jibe well with her Waspy Connecticut pedigree—it was soon discovered that her mother had died a good ten years back and bequeathed her estate to the nursing home. There was no one else. Deanna died the last in her line. Whatever things she left behind in the world were up for grabs.

“Take what you want,” Rafael offered generously as he led me into the second bedroom, which she had used as an office/library. “If you don’t, someone else will. Anything that’s not nailed down will be gone, and the rest is all going in the dumpster anyway. The landlord takes possession next week, and he’s gonna rip this place a new asshole, renovate the shit out of it and get some little yuppie fucks from the suburbs to drop at least five grand a month.”

“How much was she paying?”

“Around nine hundred, at the end.”

Nine hundred bucks for a sprawling two-bedroom in the heart of the East Village. Sure, it was a mess. The drab wooden floors were pocked and scuffed and so slanted you could put a handball down and watch it roll of its own accord from one end of the living room to the other, the appliances were ancient and cruddy and had probably been on their last legs for years, and there was a set-in mustiness that seemed one with the peeling walls and the somber space itself. But $900?

“She was probably paying no more than a hundred bucks or so when she first moved here in the late ‘60s. My mother’s got the same apartment three floors down and she pays six hundred. She laughs at these crazy blancos coming here where nobody wanted to be a few years ago, and now they’re forking over all kinds of wacky rents to live in closet-sized apartments. There’s a waitress at the coffee shop, fresh out of Minnesota or Michigan or some shithole like that, who wants to pay me a grand just to sleep on my couch.”

“That’s not bad. You gonna let her?”

“Nah.” He swiped away the thought. “A thousand bucks a month is not enough to have to look at her fat ass weighing down my couch every morning. And I think she’s looking for a fuck that I’m not interested in giving her. But anyway, go check out those books before someone else gets them.”

Even now, it is with a small dose of shame that I admit that her stash of books was a minor goldmine for me. Stacked on a sagging sofa table and scattered across the floor were novels and volumes of essays and short story collections by authors I knew and liked and others I didn’t know but was interested in discovering. There were old editions of French books that would have cost a small fortune in shipping alone, were I to order them from overseas. There were oversize art books and a nice coffee table book on Nigerian wood carvings and catalogues for exhibitions in France and New York in the ‘80s. Rafael was barking into his phone in Spanish in the living room, which left me to scour her collection without interference. Next to the table was a Whole Foods shopping bag filled with folded fabric, tablecloths or something, which I gently removed and put aside so I could fill the bag with my loot. I eagerly sifted through the heaps, making my own piles of those I definitely wanted, maybe wanted, and had no interest in, and found myself hurrying nervously as though someone was going to catch me in the act, or worse, come and start pilfering books that I was in the process of claiming. I was already feeling proprietary. They were my possessions now, Deanna’s books. Dead Deanna’s books now belonged to me, and no interloper was going to barge in at the last second and steal what was rightfully mine.

Rafael peeked in while I was neatly tucking a handful into the shopping bag, smiled, and winked at me. “Told you you’d find some stuff you like.” He seemed pleased, as though he’d gifted these things himself.

I smiled back with mild embarrassment, then put my head down and returned to the task, trying to get it done as quickly as possible.

“And when you’re through here, there’s a shitload more books in her bedroom.”

I stopped suddenly and looked up.

“You sure this is all right?” I said, feeling stupid and naive right after saying it.

“Why the fuck wouldn’t it be all right? She ain’t gonna read them anymore.”

Rafael’s commonsensical, no-bullshit way of putting it was comforting. Plus, it occurred to me that she might have liked the idea of someone with similar interests appreciating the books she held dear in her lifetime. I imagined her lying in bed with her beat-up copy of Genet’s Notre-Dame-des-Fleurs, which I had just packed away, or sitting at her little kitchen table with a sandwich in one hand and Brodsky’s On Grief and Reason in the other. I pictured her marking up selected passages and penciling in the abundant notes lining the margins of some pages, and though markings usually annoy me to no end and often preclude me from buying used books—I dislike the distraction of other readers’ ideas and comments intruding on my intimate relationship with the text—in this case it was intriguing. I was looking forward to getting a glimpse into the thoughts of this dead woman whose library I was spoliating.

“You know, you can take other things, too. Not just the books,” Rafael informed me, sprawling himself out on a maroon beanbag chair near the door and playing with something that looked like a little straw voodoo doll, absentmindedly poking the back of its head with the sewing needle he found in it. “There’s some good stuff left, but it won’t be here for long.” He made it sound like a fire sale.

“What about you? What are you taking?”

“I already got all I need. I was down here the day after she died. Me and my mother were the second ones in after the lady down the hall. She’s the one who found Deanna on the bathroom floor the night she insisted on coming home. She didn’t want to die in a hospice.” He withdrew the needle from the doll’s shoulder, stuck it between his lips like a toothpick and whistled in some air.

Rafael is a classic New York mix, one half Puerto Rican, the other half mostly Italian with a pinch of various other exotic ethnicities tossed into the tangle: a dab of Ethiopian, a dollop of Estonian. Mother from San Juan, Father from Rome. One full brother, two half brothers, and a stepsister that he despises. White on the outside, pure Spic on the inside, he calls himself. He was born and raised in the East Village, which will always be the Lower East Side for him and others like him who refuse to accept the gentrifying term levied upon the portion of the LES above Houston. Unlike many native Loisaidas, at fifty-two years old, Rafael has never left his hometown, never abandoned the squalor of the ‘60s and ‘70s or folded in the face of encroaching gentrification to flee to the suburbs or seek more spacious shelter in the outer boroughs. In fact, he’s never lived outside of a ten-block radius of where he was born, on the corner of Third Street and First Avenue. When he got married, at twenty-six, he moved into a small one-bedroom on Fifth Street between B and C, and when that pairing went south, he wound up landing an affordable housing studio on the fifth floor of a walkup on Forsyth just north of Delancey, where he’s been for the last twenty-one years, and where he plans to die. But the bulk of his formative years were spent in the stately six-story building on Second Avenue between Third and Fourth, where his mother, stepfather, and brother still live, and where I was presently rifling through a dead woman’s book collection.

We’d met about five years earlier, through a mutual friend that neither of us is currently in contact with. Initially, Rafael was somewhat suspicious of me, until he found out that I too had been born in the city, and even though my family had moved us out to the suburbs early on, having been birthed in Manhattan—only a half-mile or so southwest of his own birthplace—earned me enough street cred to avoid summary dismissal. I’d come back to my native city shortly after college, settling in several short blocks from Rafael, and I believe he views me as a returned exile worthy of welcome. Soon after our first meeting, we were fast friends. A dozen years my senior, he has become a kind of cool older cousin, and though we differ greatly in background, upbringing, demeanor, and general life interests, we share a certain bond that I have as much trouble explaining to myself as I do to others. We see each other nearly every day, mostly doing not much more than sitting in coffee shops or ambulating aimlessly around the neighborhood while he talks about how it used to be and I try to piece together how it was before I left, both of us struggling to reconcile these pictures with how it is now.

“Come here. Look at this,” Rafael called from Deanna’s bedroom.

I put one last book in the bag and headed next door, eager to see what prizes awaited me there. He was sitting on the edge of the bedframe’s steel skeleton, holding a sheaf of papers in his left hand and a rumpled old postcard—whose face displayed a picture of a lit up Sacré-Cœur at night—in his right.

“This is from 1979, this one,” he announced without looking up from the lines.

“You think we should be reading this?”

“Why shouldn’t we?”

I didn’t know why we shouldn’t, and if I was going to be honest with myself, I kind of wanted to, so I sat down next to him and picked up a pile papers from the floor.

“Nothing much here anyway. It’s from someone in France. Boring.” He shoved it back into place, unfolded a letter, and starting reading. After a few seconds he filed it behind the postcard. “Even more boring. Work shit. That’s never interesting. What do you have?”

I was holding a letter but was having trouble keeping my eyes on it. Rafael looked from me to the paper in my hand. “It’s not going to read itself,” he said.

It turned out to be another prosaic report, nothing too deeply personal, nothing to further the guilty sense of intrusion I had felt from the moment I stepped into the apartment, and conversely, nothing to satisfy the anticipation of uncovering a revelatory secret of the dead that would add some kind of profound sense of meaning to the experience. An uninspiring note from a friend in Philly about a new job, a reunion with an old boyfriend, some banal observations about turning forty. I almost made it to the end of the first page and stopped. We tried one more: a long, meandering and mundane missive from an ex-lover, composed in broken English in which I could almost hear the accent, much less absorbing than hoped for.

“No good.” He grabbed it from my hands and filed it away and put the whole stack of correspondence back in place. “Bottom line, everyone’s life is just basically boring. It’s a fucking shame, is what it is.” He got up and walked toward the door and then turned around with a constipated expression on his face. “You make it through all the terror and tedium of life and what do you get for your time and effort? You get dead, that’s what you get. Good and dead. Nothing else.” He pulled back his long curly greasy shoulder-length black hair and walked down the hall toward the kitchen, mumbling and/or humming as he went.

After I’d filled two shopping bags almost to bursting, we sat across from each other in Deanna’s living room, Rafael in the big brown recliner that would soon be Eric’s, and I on the as yet unclaimed daybed, wondering how many hours Deanna had whiled away in this very spot. The TV stand seemed forlorn without the TV. Next to it, a monstrous mahogany breakfront cabinet was still full and probably the only untouched item in the place, as though breaching its interior and plundering the personal miscellany therein—mostly photographs and a few pencil sketches—would call a curse down upon those bold enough to steal images of the dead. Or maybe it was simply because no one had much interest in or use for anything inside; whatever meaning those things held had been swallowed by the same void that devoured Deanna. Behind its glass doors was an array of framed photos spanning her life, snapshots of her in early adolescence with hints of blooming beauty on some bucolic country field; in her twenties, young and smooth-skinned and sanguine; then slightly older, her lids hanging heavy over her eyes and her skin sagging around her jawline and the hopefulness tempered by middle-aged resignation and urban isolation; and finally, nearing the end, with her sunken cheeks and blackened eye pits, the spectral gaze looking past the camera and out of the photo into something else. Maybe this was the game I’d been hunting, a hint of this something else. Perhaps I’d wanted to savor the aftertaste of death, to snuff the scent of individual extinction and get high, in a way, on the vapor of obsolescence.

I’d never known this woman; I had never met her or talked to her or seen her or even been in her presence. She was less than a stranger to me.

The earliest photo was a surprisingly sharp black-and-white of a carefree little ten or eleven-year-old girl smiling somewhere in the backyard woods with a house haunting the distance behind her. It was in a bold black frame next to the latest, which had to have been taken shortly before her death, as she was lounging on the very daybed I was sitting on, haggard and hollow-eyed, only her wan and waxen yet still-smiling face and one emaciated arm visible while the rest of her withered body lay mummified under a thick woolen blanket. (I found myself wondering where the blanket was, probably among the first items to be pilfered.) There was a conspicuous lack of other people in the collection of photographs—just one with Rafael’s mother, sipping milkshakes at the counter of an ice cream shop, and another with a woman on the steps of Montmartre, sitting closely next to each other with beaming smiles and a pile of books at their feet—as though it were an adumbrated timeline of her life, the bare-bones testament to an existence that has simply come and gone like any other, sprouted up and had some time in the sun before quietly sinking back into nothingness. But I couldn’t focus on any of the in-between pictures. I kept going back and forth from the old black-and-white to the near-deathbed shot, trying to reconcile the two disparate subjects as somehow the same being, this buoyant little preteen and the moribund older woman, separated only by a few years that in geologic time amount to nothing more than a split-second at best, the tiniest pin prick in the fabric of space-time. Deanna at twelve, young and happy and healthy, and Deanna sick and dying at sixty. Nothing in between, nothing apart from these diametric poles of relevance, seemed to hold any import.

“She wasn’t bad looking when she was young and healthy, huh?” Rafael offered, noticing me noticing the photos.

“She was definitely younger and healthier.”

“Yeah. She was in her twenties when she got here. Man, was this a different place back then.” He sat back and breathed in deeply—the air was stale and reeked of mothballs and lingering sickness—looked around and suffered a sudden fit of nostalgia, which seemed to happen to him fairly regularly, afflicted as he often was by visions of the old, dead NY. Most of us are plagued by the past from time to time, pining for those lost places of youth, but for Rafael it was more unique than usual. He still lived in the same physical area in which he grew up, but the exceptional changes that the area had undergone over the course of the decades of his life made it nearly as unrecognizable as a foreign country. Urban renewal is one thing; what New York City—especially Manhattan—has experienced, is more like transmogrification. “The shit I’ve seen growing up on these streets, you couldn’t make up. I’ve learned more here than I could have in any college in the world,” he proudly asserted, shaking his head. “Fifty-two years in this neighborhood. Half a century in this city. I was born on the Lower East Side and that’s where I’ll die. They can’t push me out. They can’t buy me out. They can build as many ugly glass buildings as they want and fill them with as many yuppy fuck scumbags that they can get to pay their bloated fuckin rents, but they ain’t never getting me out. Not as long as I’m breathing. I was here before them and I’ll be here after they’re gone.”

I strongly disagreed with the second half of this last statement but thought it best to keep my dissent to myself. It’s not that I’m afraid to contradict Rafael, but even though he is known to spew a lot of rubbish in general, much like the dogma of Papal infallibility, when he speaks on matters related to “the neighborhood,” he is pretty much preserved from the possibility of error. He has a nearly eidetic memory when it comes to the city, and he can tell you without a moment’s hesitation what the laundromat on the corner used to be in 1981, or in what dark alley his old pal Nice-guy Jimmy OD’d when they were fifteen, or what Ed Koch was wearing when Rafael saw him sipping a chocolate egg cream on the corner of Second Avenue and Seventh Street twenty-nine years ago.

“Guys like me, we paved the way for these people. You think these little hipster fucks with their tattoos and skinny jeans and their funky fedoras would be walking down Stanton Street at night in the ‘70s?”

He seemed to be waiting for an answer. “I guess not,” I said, but did not go so far as to ask exactly how he and others like him paved anyone’s way anywhere.

“You bet your ass you guess not. Eleven years old and I was out hustling on these streets. These little punks today, they wouldn’t’ve lasted ten minutes in this neighborhood thirty years ago. These little suburban sluts you see walking around with their asses hanging out of their jean shorts, strutting down the block like it’s no big thing… You know what would’ve happened to girls like that down here in the late sixties, seventies?” He pulled his torso toward me and jutted his head forward like an ostrich and raised his chin and puckered his lips defiantly.

“Nothing good?” I ventured.

“You’re fuckin right, nothing good!” he yelled. “They would’ve been mugged and beaten and raped, then killed and chopped up. And then raped again. And then left on the street for dead or dumped on the side of the highway like road kill. That’s what.”

He was rather riled up—one might go so far as to say he was downright tickled by the scenario—so I didn’t dare question the physical feasibility of his hypothetical chronology.

“Things change,” is all I said.

“Yeah.” He sat back in his chair and looked out the window, which gave onto the brick siding of the neighboring building. “But that don’t mean it’s a good thing. It’s because of these fuckin interlopers that the people who are from here can’t afford to buy a decent cup of coffee anymore, let alone live here.” He winked at me and elbowed me in the ribs, a little harder than he should have. “Lucky I got rent control.”

I’d estimate conservatively that about sixty to seventy percent of what Rafael spouts is unadulterated bullshit, but it is usually very entertaining, and once in a while he’ll floor me with some inadvertent profundity, an impulsive nugget of wisdom that seems to fall almost accidentally from his mouth while chewing on other concepts. But in fact there is nothing accidental about it. Though not formally schooled, Rafael is about as sharp as they come, in some ways. His official state education stopped after his second year of vocational school, where he was studying automotive repair. After dropping out, he went to work in the claustrophobic kitchen of a well-known little luncheonette on Second Avenue near Saint Marks Place, sweating it out there for a solid decade before landing a plum job as the private chef of a wealthy Upper West Side socialite, for whom he prepared three square meals a day, six days a week, for another decade, before his employer died of complications from renal failure. Her younger husband—who had never much cared for Rafael or his cooking—promptly relieved the chef of his duties but could do nothing about the hundred grand his wife had left the latter in her will, which has since allowed him to exist without a job. His expenses are low, his needs are modestly met, and his tastes are simple, so Rafael doesn’t plan on seeking employment anytime soon. “I’ve been working since I’m thirteen years old,” he rationalizes. “I think I’ve earned a break.”

We sat there in the dead woman’s overheated living room holding plastic cups full of lukewarm tap water that neither of us was drinking, while Rafael spun yarns about the glory days in dirty old New York well before my own birth. I’d heard most of these tales already—he loves to regale me with war stories about the mean streets of his youth, as though he were a soldier that barely made it out of a combat zone when so many others weren’t as lucky—so I just nodded and zoned out and occasionally tuned back in and chuckled appreciatively when it seemed appropriate, which worked well for both of us because he was talking mostly for his own benefit, and the bubbling sonority of his voice provided a nice counterpoint to my thoughts. I was thinking about how pleased I was with my new acquisitions, how much I was looking forward to going home and unpacking them and flipping through their pages before strategically arranging them on my bookshelf, and how, despite whatever misgivings and initial feelings of guilt were afflicting me, I had very much wanted to sift through Deanna’s personal artifacts and cull the best of her books, to walk the space she once inhabited and spend some time in the last place on Earth this lady had called home. In fact, I had been looking forward to it all day, since Rafael had called me earlier and proposed our coming here. Beyond a goody bag, I had been hoping to come away with some sense of this woman that I’d never known, of what it might have been like to be here, to live here, in this apartment, in this city, all those years back.

I don’t know what exactly I was expecting to discover, but what I felt most was the quietly ominous presence of absence, nothing so much about Deanna as about her not being there, this unsettling sense of something missing, even if I wasn’t sure exactly what that something was. I’d never known this woman; I had never met her or talked to her or seen her or even been in her presence. She was less than a stranger to me. We lived a few blocks apart, might have crossed each other anonymously in the street every day or sat at neighboring tables at a local café without knowing it. We shared the same city for years, though we didn’t exist in each other’s worlds. But now, the fact that she didn’t exist at all in the world, and that I was here in her apartment appropriating her earthly possessions, made her somehow more real to me than if I’d met her in passing on the street or had been hastily introduced to her in the hallway of Rafael’s mother’s building. I felt a sort of intimacy with her, as though she’d imparted some small but significant secret through the things of hers that had passed on to me, through the short amount of time I’d spent in these rooms in which she’d lived and loved and died.

By now Rafael was snoring loudly. His head hung back on the recliner’s headrest and his mouth gaped ceilingward like a black hole sucking in the lamplight. He does this often, doze off during a brief lull. I’ve long suspected he might have a touch of narcolepsy, but he always has some kind of excuse. I sat there listening to his rhythmic wheezing and stared a bit more at the photographs as the doorknob turned and footsteps approached and a short, stocky bald guy in a stained black sweatshirt and dusty brown khakis came in and stopped at the entrance of the room.

“Oh—oh,” he stammered, looking from me to the sleeping Rafael to me. “I didn’t realize anyone was in here. I just came to get something that belongs to me.” And he scurried off into the bathroom.

A few seconds later Rafael’s head snapped up and he was at full attention, as though he’d never slipped from consciousness. He looked around suspiciously, sniffing the air like a bloodhound searching for a scent.

“What happened?”

“You fell asleep,” I informed him.

“For how long?”

“Five minutes or so.”

He seemed pleased by this. “Yeah. I’ve been practicing power-napping. I try to keep it between three and seven minutes. Five is perfect. I’m getting good. What was that noise?”

“Someone’s here. In the bathroom.”

He lurched forward and whipped his head around and the guy came out on cue, holding a battered white hair dryer and wrapping its cord around the handle and stopping short in front of Rafael as though caught robbing the grave.

He smiled timidly. “Hey Rafael.”

“Al,” he replied coldly, and nodded. “I didn’t hear you come in.”

“Didn’t want to wake you. I only dropped by for this,” holding up the blower shyly. “Forgot it last night.”

“That’s spoken for, Al. I’m taking it.”

“Spoken for? It was just sitting there.”

“It’s mine. I’m taking it.”

“If you were taking it, why didn’t you take it?”

“I was going to take it now.” His voice maintained its icy monotone. His eyes were fixed on a point midway up the wall behind Al. “Just sat down for a power nap.”

“Oh yeah? How long?”

“Five minutes.”

“I try for fifteen to twenty-nine.”

“Too long.” Rafael closed his eyes and shook his head and his hair swung from cheek to cheek. “Got to be under fifteen to be a true power nap. Otherwise it’s just plain sleep. But anyway, the dryer’s mine.”

Al smiled down at his booty and spoke hesitantly, apologetically. “The thing is, there was no note on it or anything. I mean, you know how these things work. First come—”

“The dryer’s mine, Al,” he stated firmly, an iota of ire rising in his voice as he stared unflinchingly at the wall.

“Fuck, Rafael.” He broke down like an impetuous child who feels he’s in the right but knows he cannot win an argument with an elder. “I really wanted this thing. I need it.”

“You got like three strands of hair combed over that cue ball you call a head. What the fuck do you need a blower for, to dry your scalp?”

“If you must know, I have a really hairy body.” He blushed, turned his head up and away in embarrassment, and pulled down the collar of his sweatshirt to reveal a thatch of curly black hair as though it were some sort of scar he’d been forced to show as proof of battle. He let go of his shirt and looked at Rafael, then at me for corroboration.

“Yep,” I said. “That’s a lot of hair.”

“Goddamnit, Al,” Rafael hissed and shielded his face. “I didn’t need to see that shit. You gotta shave that fuckin burger meat. Transplant it onto your head or something.”

Al smiled graciously and pushed up the nose pads on his glasses, which sat lopsided on his face, the right lens hanging a good quarter of an inch below the left. “Nah. My girlfriend likes it. She thinks it’s manly.”

“Since when do you got a girlfriend?”

He cocked his head and scrunched his eyebrows. “I don’t think I appreciate what you’re implying. I thought we were friends, Rafael.”

Rafael huffed and looked at me conspiratorially, then turned back to Al with a lazy stare. “Whatever. You’re still not leaving here with that dryer.”

“Possession is nine tenths of the law.”

“That still leaves one tenth,” Rafael countered calmly. “Put it on the table.” He arched forward and pointed to the object in question, lowering his finger to indicate the sofa table in the middle of the room, awaiting satisfaction, elbow poised uncertainly on the armrest.

They stared at each other like duelers preparing to draw. Al’s hand slowly tightened its grip on the handle of the dryer as silence seemed to siphon air from the room, causing a kind of pressured environment that was primed to blow. The little bald man seemed somehow menacing now, completely different from the mousy milquetoast that had walked in only a few minutes earlier. His maxillary incisors hung over his lower lip like fangs, and his eyes were reduced to louring slits. He wanted that dryer. He felt entitled to it, as though dead Deanna had explicitly bequeathed it to him; it was his by right of succession, and he wasn’t going to relinquish it without a fight. For a few seconds I sincerely believed there was going to be violence over this. Rafael was never one to shrink from confrontation—on the contrary, he was drawn to it—and Al seemed ready to risk physical injury in defense of what he believed was justly his. And I was prepared to sit back and watch these two middle-aged men trade blows over a dead woman’s hairdryer, laying mental odds on how badly Rafael would thrash him or what kind of upset it would be if bald little Al bested my tough-guy buddy. If this was going to happen, I was going to enjoy it. With my right foot I slowly nudged my bag of books out of harm’s way and sat back comfortably.

Female voices rang out in the hallway. A high-pitched laugh. Heels echoed through the corridor. A siren blared below the window. Al’s features softened into pathetic sadness. He lowered his eyes and held up the blower in both hands like a silent supplicant reluctantly offering sacrifice to an intransigent deity.

“Ah, fuck it.” Rafael threw up his arms and leaned back, completely deflating the situation. “Take the fucking thing. Dry your scalp, your chest hair, your fucking ball hair. Go ahead. Just get the hell out of my sight before I change my mind.”

“Oh man, thanks Rafael.” Almost teary eyed, Al took a stutter step toward the chair as though he was going to wrap Rafael in a grateful embrace, then thought better of it. Instead, he put down the dryer and reached into a paper shopping back at his feet—which I hadn’t noticed before—pulled out a blender whose glass tumbler was smeared with fruit remains, and held it out to Rafeal. “You want this? Looks barely used.”

“Nah. I got a juicer at home. Paid over a hundred bucks for it and never even use the fucking thing.”

He extended it next in my direction.

“No thanks. I hate fruit.”

Al seemed relieved and replaced the blender in the bag. He bowed low at both of us and skirted quickly out of the room. We listened to him rumbling around the kitchen for a minute or two, heard the rustling of the paper bag and then the quiet opening and closing of the door as he left the apartment.

“I hate that fuckin guy,” Rafael mumbled, thumbing toward the door. “Forty-five years old and still lives with his mother. If she wasn’t friends with my mom I’d throw him a beating that would make his bald head spin.” He shook his head in disgust. “Only girlfriend that little twirp’ll ever have is his sweaty right hand.”

“It was nice of you to let him have the blower.”

“Ah. I didn’t even want it. I got three of those things home.” He leaned forward and pulled his hair back into a makeshift ponytail. “I just didn’t want him to have it.”

It was now nighttime proper, and the apartment had settled into shadow and soft lamplight.

“We better get going,” Rafael announced after a few minutes of drowsy silence, or I’m gonna fall asleep again. This chair is too comfortable.” He patted its fluffy armrests and looked around at its encompassing girth.

“Too bad it’s already claimed.” I raised my chin toward the piece of paper labeled ERIC!!!

He smirked. “Possession is nine-tenths of the law.”

Before leaving, I gave the place a last once-over, picked up another book or two—might as well, I reasoned, because if I didn’t, someone else would have—and a small, framed watercolor of a serene shoreline sunset that was hanging above her fridge, all creamy gold and muted yellow and burnt umber. Rafael stopped at the door and looked back into the room.

“You got everything you want?”

“I got as much as I can take,” I said, holding up two full bags. I was already dreading the four and a half block walk home.

We stood there gazing over the apartment that would soon be razed.

“It’s a shame,” I said.

“It’s not. We die. That’s what we do best. It’s not a shame. Not at all.”

“No. It’s a shame that we don’t get to take our shit with us, like the Egyptians believed. It would be nice to wake up in the afterlife with whatever stuff was buried with us.”

He considered this for about two seconds. “I don’t know. I think I’d get bored with them. One lifetime is enough for me.”

“Still. To spend all those years accumulating all that stuff, and then to just leave it.”

“He who dies with the most toys . . . still dies.” He laughed. “I read that somewhere but can’t remember where. I try not to read anymore.”

“Why?”

“Because you can’t trust anything you read these days. I guess you never could, but it seems worse now. I blame the Internet. Everything’s the Internet’s fuckin fault. It’s nice to have something to blame.”

We stood there for another ten seconds or so. Then Rafael shut the light and we left, and I sweated and struggled homeward while he went upstairs to his mother’s.

Deanna’s books are in a pile on the floor of my living room, squeezed between one of my bookshelves and the side of the couch. I haven’t yet managed to integrate them into my library. They’re fine books. I plan to read some or most of them one day, as I plan to read most of the unread books of my own, though a good deal of them will surely remain unopened. I sometimes wonder where they’ll end up when I’m gone.

I don’t keep Deanna’s books apart out of guilt or disgust or because of any kind of negative association. They just don’t feel as though they belong to me. They don’t feel like my books. Not in the same way that a library book doesn’t feel like mine, or a novel borrowed from a friend feels only like temporary ownership. These particular books exist in a kind of limbo. They are no longer Deanna’s, but they are not—and never truly will be—mine, any more than they were ever truly hers. The things we leave behind are not really left behind, because we don’t go anywhere—we just stop, we just quit being—and thus cannot leave anything. And those things of ours that we cling to during that evanescent interval between birth and death, from the sacred and cherished objects to the charmingly forgettable tchotchkes that we acquire and accrue over the course of a lifetime, never really belonged to us in the first place. Ownership is a fallacy. At best, we can say we existed side by side with them for a while, that we fortuitously shared a slice of time on Earth with other things—animate and inanimate—and ultimately with ourselves, these bodies we rent and have no choice but to vacate when the lease expires. Kant tells us that we can never truly know the thing in itself. Descartes tells us that we can never truly know ourselves, this I that thinks. There is an unbridgeable gulf between us and the things of the world, between ourselves and other people, and at last between ourselves and our selves. Is it this abyss that makes living sometimes so difficult, so painful? This frustrating inability to truly connect with anyone or anything, this distance from everything we encounter during our existence, including ourselves?

I’ve always felt uncomfortable with those eulogistic euphemisms and funeral oratories that say our loved ones are not gone so long as we remember them, that the dead are somehow not dead while they live on in our hearts. I understand the motivation behind wanting to believe this, and I fully appreciate the difficulty of living with loss and the pain of seeing your loved one’s remains gussied up and stuffed in a box and buried under a mound of earth and grass and granite. I know firsthand the heartache of having to say goodbye forever. At some point most of us do. In the end, death in New York is really not much different from death anywhere else, from death in Kansas or Calcutta, Death in the Afternoon or Death in Venice or Death on the Installment Plan. It’s just death, any way you cut it. “All plots tend to move deathward,” Don DeLillo writes. “That’s the nature of plots.” Thusly, deathward move the plots of our lives. Deathward the course of empire takes its way. Till death do us part.

But part we must, from all the things of this world, including the most intimate, our bodies, our selves. Whether that parting takes place in bustling Midtown Manhattan or in some lonesome log cabin in the mountains or anywhere in between, it might seem different based on where death comes to pick us off—at least to those witnesses whose time has yet to come—it might seem as though death in New York is sui generis because of the unique pace of life in this sleepless city, but that’s just it: the hasty and hectic nature of life here only makes death seem different, maybe a little less permanent, less effective, somehow not as real. But death is consummately democratic, and life ultimately has no bearing on death, no matter how it was lived. Once dead, life has no more dominion. There is no overlap. “Death,” Epicurus famously said, “is nothing to us, since when we exist there is no death, and when there is death we do not exist.” We, along with the things we encounter during our allotted time, eventually become part of the great fickle fiction of history. “The last act is tragic,” wherever the play is performed. The actors leave the stage to applause or jeers and a new scene with fresh players is put on, the set changes, the props are replaced, and sooner or later the storyline is forgotten, all narratives are negated, history is erased, time moves on until it doesn’t. And these things we leave behind, these minor mementos of our own individual biographies—the hosiery and hairdryers, the books and furniture and bedsheets and toiletries, toothbrushes and washcloths and shower curtains and computers—are fossil evidence that we once existed, that we were here, for however short and insignificant an interval. We were here, the things we leave behind say, until they lose their identity as well, an assumed identity ascribed to them by our own flimsy existence. And like the towering monoliths of Manhattan that attest to the great and glorious lives of those inhabitants who roamed the same streets before us, who built this place in which we now live our speedy, deathward lives, the things we leave behind will one day be left behind, and in their place will rise other things that will in turn be left behind, until the last thing remains and then nothing is left to be left, nothing will be there to acknowledge or be acknowledged. No survivors, no witnesses.

Nothing there to say, We were here.

Frank Cassese was born in New York City and raised on Long Island. After graduating with a degree in philosophy, he lived and worked in France before returning to the US, where he has taught English and writing at various universities. His work in Guernica was selected for the notable section of The Best American Essays 2013, and his first novel, Ocean Beach, was published in 2014. He has a new novel scheduled to appear in late 2018. He lives in Manhattan’s East Village.