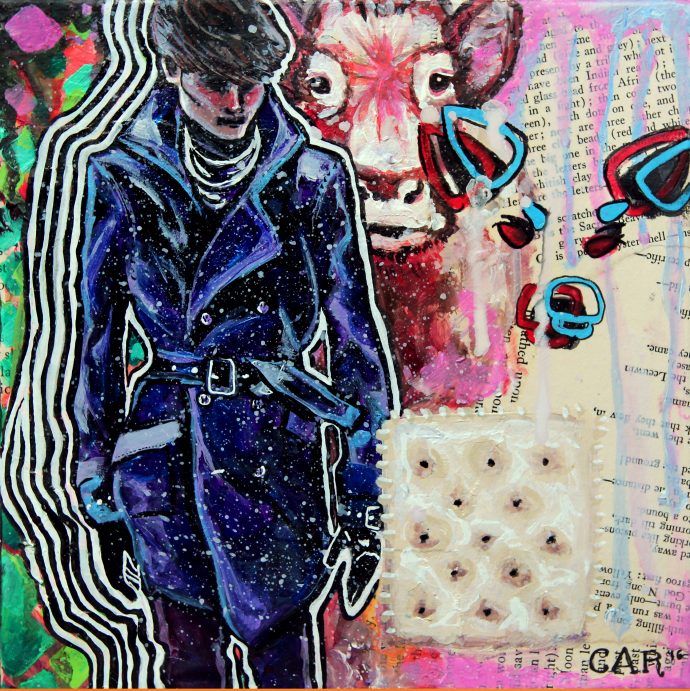

Red ass, purple heels, four Chihuahuas

Self-Portrait with Herbarium

I bought pre-moistened bathing cloths for invalids

in order to avoid the shared bathroom and shower.

I did not want to eat with the others, so I lived on

Saltine crackers I stored in a metal container to keep

away moisture, and wormy apples from the orchard.

I walked the grounds only after dark, and often

ducked beneath the low arbor to visit the graves

of the founders to thank them for the trees

and meadows, the small gray squirrels and the toads

that leapt with every step I took, and all the plants

that composed my herbarium. I took pleasure less

in the plants themselves than in their categorization.

I went to the library often, but only in the dead

of night. We each had a key, which revealed to me

a degree of trust that seemed, at best, naïve.

Some nights, but rarely, I came upon some other

lost soul out looking at the moon, which was gold

and swollen. I worried—did she?—that it would

break open and spill its seed over the meadows.

To me, the animals, deer and foxes and such,

seemed terribly lonely. Even the pond shivered

in its loneliness, and the mountain, for as far

as the eye could see there was nothing

to which it could compare itself. Owls called out

to each other but were only answered by cemeteries.

How did I return to the world? One night

I walked beyond the stone gate, not through

any intention of escape, but only to seek a rare

flower I could press in the pages of a heavy

book and add to my collection. One quiet

foot in front of the other until I found

myself walking faster, as if pursued,

though no one was invested in calling me

back. Still, at dawn, I felt like a freed prisoner.

The purple night lifted its heavy curtain

on a day like an unripe peach, orange and softly

green and curved. Mist lifted away

from the fields revealing that what I’d thought

were boulders were actually cows, reddish,

lifting their white faces to look in my direction.

Diane Seuss’s most recent collection, Four-Legged Girl, was published in 2015 by Graywolf Press and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open won the Juniper Prize and was published in 2010. Her fourth collection, Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, is forthcoming from Graywolf Press in 2018. Seuss is Writer in Residence at Kalamazoo College.